The section of the book of origins which is offered as the Gospel reading this coming Sunday (Matt 22:34-40) reveals the fundamental commitment which Jesus of Nazareth had to the Jewish faith and ethic with which he was raised.

The Jewish nature of Jesus is evident right throughout this book, and indeed in each Gospel account in our Bible. The Torah and the covenant with God which were so important for Jesus, also undergird contemporary Judaism and continue as fundamental to the Christian life.

This is made very clear in the first part of this week’s passage (Matt 22:34-40), when Jesus engages in conversation with a teacher of the Torah (the law). To the question, “which commandment in the law is the greatest?”, Jesus responds by citing two, each drawn from Hebrew Scripture, noting that he has quoted “the greatest and first commandment … and a second, like it” (Matt 22:38-39).

Love God. The first commandment cited by Jesus, “love God” (22:37-38), comes from Deuteronomy, the book which provides a comprehensive report of “the statutes and ordinances that I am teaching you to observe” (a phrase which occurs regularly—4:1,5,8,14,40,45, 5:1,31, 6:1,20, 7:11, etc).

Specifically, the command to “love God” is located immediately after The Ten Words were given to Moses and through him to the people (5:1-33), at the very start of the long recital of these “statutes and ordinances” (6:1-26:19).

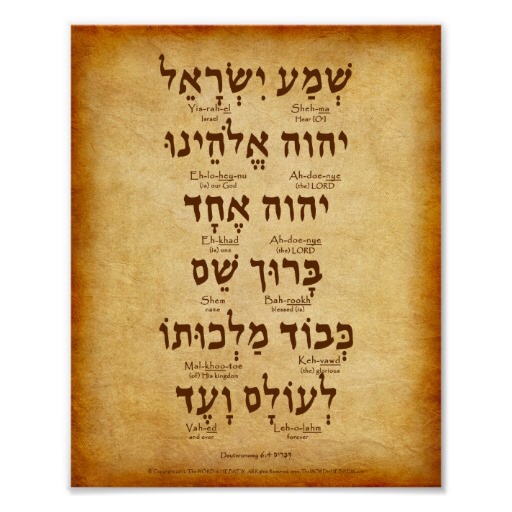

Indeed, this commandment is nestled into the passage which forms the basis of the daily prayer of faithful Jews: “Hear, O Israel: the Lord is our God, the Lord alone. You shall love the Lord your God ….” (6:4-9). The prayer is known as the Shema (שְׁמַע), which is simply the opening word in Hebrew: Hear!

The offering of these words in prayer twice each day is in response to the clear instruction to “recite them with your children and talk about them … when you lie down and when you rise” at all times (Deut 6:7). To this day, it is traditional for Jews to seek to say the Shema as their last words, and for parents to teach their children to say it before they go to sleep at night.

This portion of Deuteronomy also contains the instruction to “bind [these words] on your hand, fix them … on your forehead, wrote them on the door posts of your house and on your gates” (Deut 6:8)—from which the classic traditional pious Jewish garb is derived.

The third century document, the Mishnah (Berakhot 2:5), links the reciting of the Shema with re-affirming a personal relationship with God’s rule. Reciting the Shema was considered to be akin to “receiving the kingdom of heaven.”

In developing Jewish tradition, two additional texts were added to the Deut 6 text, to produce an expanded Shema: Deut 6:4-9, the fundamental instruction to love God; Deut 11:13-21, reiterating the words about binding and talking, and the blessings that ensue; and Num 15:37-41, reiterating the words about fringes as an important reminder to be obedient to God.

Centuries later, the Talmud points out that subtle references to the Ten Commandments the can be found in the three portions, so the Shema is seen as an opportunity to commemorate the Ten Commandments.

The importance of this commandment is clear in Hebrew Scripture, and continues in the tradition which Jesus has inherited, in that “love God” is the fundamental commandment.

Love Neighbour. The second commandment which Jesus cites, “love your neighbour” (22:39), comes from Leviticus, a book whose name comes from a Greek word derived from the priestly tribe of Levi, as many of its laws relate to priests.

Leviticus unfairly bears a negative reputation, our time, for containing pages and pages of “boring, archaic, irrelevant” laws and regulations. (That is, unless you are talking about *that issue*—in which case Lev 18:22 and 20:13, taken quite out of context, suddenly become of primary and enduring significance.)

The command to “love your neighbour” culminates a series a instructions regarding to the relationship with neighbour: “you shall not defraud your neighbour .. with justice you shall judge your neighbour … you shall not profit by the blood of your neighbour … you shall not reprove your neighbour (19:13-18).

It sits within the section of the book which is often called The Holiness Code—a section which emphasises the word to Israel, that “you shall be holy, for I the Lord your God am holy” (Lev 19:2; also 20:7,26).

found in cave 11 at Qumran, the which contains

the oldest known copy of the Holiness Code.

Holiness was central to the people of Israel. Those who ministered to God within the Temple, as priests, were to be especially concerned about holiness in their daily life and their regular activities in the Temple (Exod 28-29; Lev 8-9). The temple priests claimed their role as the authorised interpreters of the Torah, and they were responsible for determining how the matter of holiness was to be worked out in the system of sacrifices brought to the Temple (Ezekiel 44:15–16, 23–24).

Pharisees and scribes alike specialised in the interpretation of Torah and in the application of Torah to ensure that holiness was observed in daily living. They undertook the highly significant task of showing how the Torah was relevant to the daily life of Jewish people.

Whilst the Pharisees clustered around the larger towns in Judea, the scribes were to be found in the synagogues of villages throughout greater Israel, and indeed in any place where Jews were settled. Their task was to educate the people as to the ways of holiness that were commanded in the Torah. It was possible, they argued, to live as God’s holy people at every point of one’s life, quite apart from any pilgrimages made to the Temple in Jerusalem. So there was already an “alternative pathway” for living out holiness in daily life.

“Love your neighbour”, then, was a critical way by which the life of holiness was to be demonstrated.

In this context, then, Jesus reinforces the centrality of loving God in all that we do in our discipleship, as well as underlining the importance of loving our neighbour in all that we do. On these two commandments, says Jesus, “hang all the law and the prophets” (22:40).

That peculiar term, “hang”, has very clear resonances in Jewish tradition. In the third century document, the Mishnah (Hagigah 1.8), we find the claim that “the rules about the Sabbath … are as mountains hanging by a hair”. Centuries later, the Babylonian Talmud (b.Ber. 63a) makes the affirmation that Proverbs 3:6 (“in all your ways acknowledge him”) is “a short text … upon which all the essential principles of the Torah hang”.

Jesus’ affirmation of these traditions of his faith have carried on in the movement which was initiated in the years after his life, death, and resurrection. Paul of course, affirms that “love is the fulfilling of the law” (Rom 13:8-10) and that “the whole law is summed up in a single commandment” (Gal 5:14). In both places he explicitly quotes Lev 19:18.

Centuries later in the developing Christian tradition, Augustine wrote that “all of God’s commandments … are carried out in the right manner when they are motivated by love of God, and because of God, for our neighbour” (Enchiridion 32.121). Still later, the 9th century mystic Theodore of Edessa affirmed that “love unites and protects the virtues” (A Century of Spiritual Texts 83).

We stand on the shoulders of a long line of Jewish faithfulness.

See also https://johntsquires.com/2020/10/01/producing-the-fruits-of-the-kingdom-matt-21/ and the Uniting Church Assembly Statement on Jews and Judaism, https://assembly.uca.org.au/resources/key-papers-reports/item/1704-jews-and-judaism