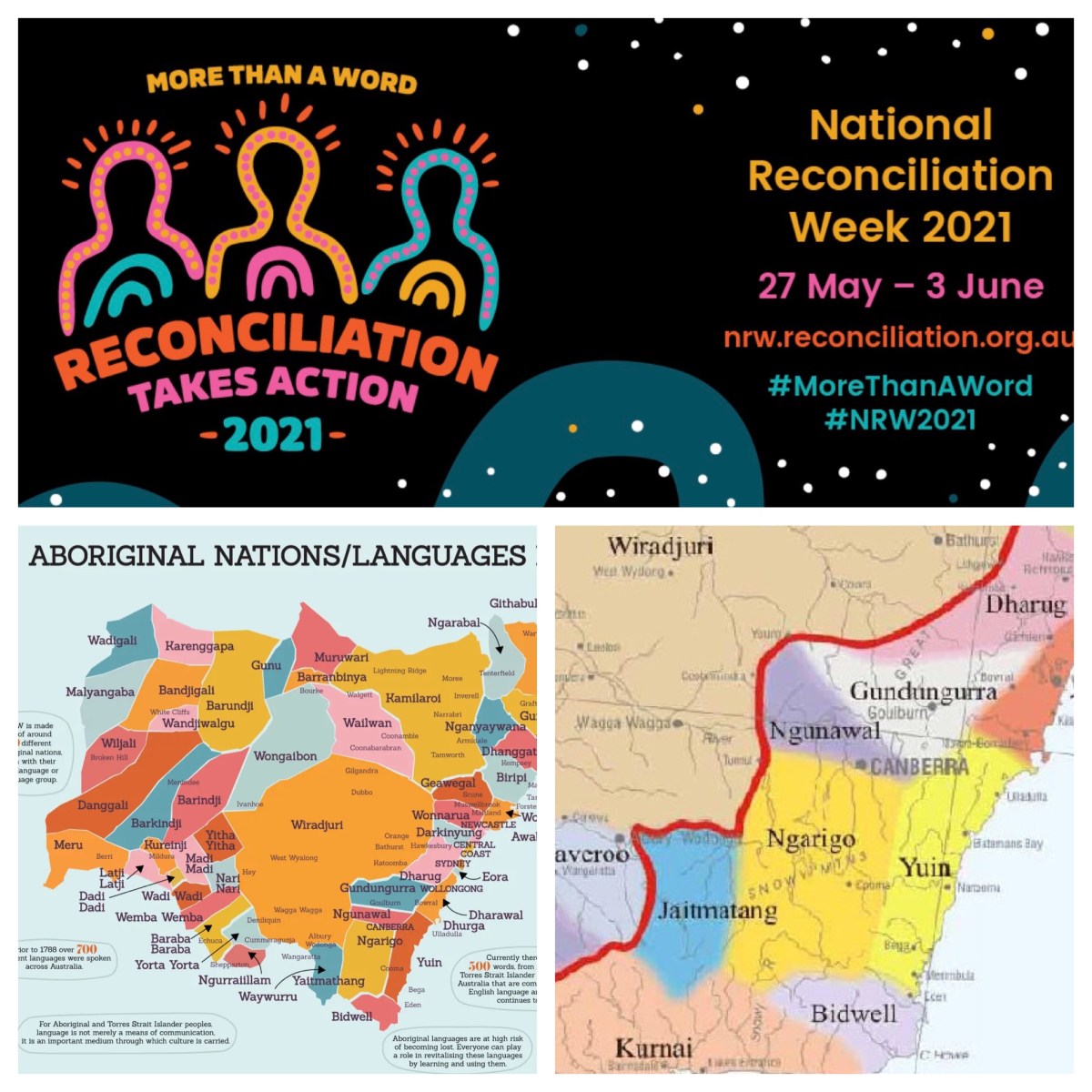

Today we are in the middle of National Reconciliation Week. The week runs from 27 May, the anniversary of the 1967 referendum which recognised the indigenous peoples of Australia and gave them the right to vote, through until 3 June, the day in 1992 that the legal case brought by Eddie (Koiki) Mabo was decided and the lie of terra nullius was laid bare by Koiki in the Australian High Court.

Today, in the middle of this week, is Reconciliation Day in the Australian Capital Territory. Reconciliation Week was initiated in 1996 by Reconciliation Australia, “to celebrate Indigenous history and culture in Australia and promote discussions and activities which would foster reconciliation”. Reconciliation Day was only gazetted for the ACT in 2018. It’s another public holiday for Canberrans—but the ACT government reminds us that it provides “a time for all Canberrans to learn about our shared histories, cultures, and achievements, and to explore how each of us can contribute to achieving reconciliation in Australia”.

This year, as I reflect on the importance of reconciliation for the people of this nation, I am struck by the names we use, and their significance. I am thinking particularly of place names. There are many, many locations around the continent which bear names that have been imposed on those locations by invading colonisers without any regard for what names were already used by the people living there before the British began their colony at Port Jackson.

The suburb where I live, Gordon, bears the name of a man who was born in England but came to Australia where he was a jockey and police officer, and for a short while also a politician—Adam Lindsay Gordon. (Who knows why??) The suburb where I grew up as a child, Seaforth, bears the name of a loch in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland (perhaps, bizarrely, because it reminded someone of that locality?).

There are other locations which bear names that refer to local indigenous people, or to specific incidents that took place in past years, involving indigenous people. You may have driven past Blackfella’s Gully, or Slaughterhouse Creek, or Nigger Creek, or similar names. They sound innocuous. They may not necessarily have been so.

Some sites identify specific massacres during the Frontier Wars. There is The Leap, in northern Queensland, where an Aboriginal woman leapt with her child, choosing suicide to avoid capture or killing by European vigilantes and Native Police. There is Red Rock, in NSW, where the name recalls the Aboriginal blood shed in a conflict there. There is Battle Hole, and Skull Hole, and no less than eighteen Skeleton Creeks, named for obvious reasons. (See https://press-files.anu.edu.au/downloads/press/p286811/html/ch08.xhtml?referer=&page=11)

There are other locations—quite a significant number of locations—that bear the name that has long been given to that location by the indigenous people of the area. The region where I live, Tuggeranong, bears a name which is said to be derived from a Ngunnawal expression meaning cold place. And at the moment, that feels like an entirely appropriate name!

From the earliest colonial times, the plain extending south into the centre of the present-day territory was referred to as Tuggeranong. The indigenous name was kept. I understand there is a rock shelter just a few kilometres from where I live, which dates Ngunnawal activity here at 20,000 years ago into the last Ice Age. They may have lived here much longer than that, possibly 60,000 or more years.

From the front of my house, I look out across to the Brindabella ranges—a formation bearing a name which is said to derive from an Aboriginal word meaning two kangaroo rats. However, another account claims that brindy brindy was a local term meaning water running over rocks, to which “bella” was presumably added by the Europeans as in “bella vista”. The British who invaded and colonised the area did such a comprehensive job of removing the indigenous locals from the area, that knowledge of the precise origin of the name has been lost.

The local nation, the Ngunnawal, shared the region we know as Canberra with a number of neighbouring nations, gathering during late spring for the arrival of the bogong moths. It was a time of feasting and ceremonies for those who joined with the Ngunnawal people.

The Ngambri came from the Limestone Plains (the area on which central Canberra sits today), although they are seen by some as a clan within Ngunnawal. The Namadgi people was a group inhabiting the high country to the west of modern-day Canberra (the area is gazetted as the Namadgi National Park). The Ngarigo people inhabited areas in the north and to the east of Canberra. There are also suggestions that some from the Wiradjuri people from the Central West participated in these regional gatherings.

These nations gathered at the place that today we call Canberra. The region is generally understood to have been a meeting place for different Aboriginal clans, suggesting that there was a reliable food and water supply. The name is believed to have been derived from a local Indigenous word Kamberri, which identifies the location as a meeting place of these many nations, for a gathering focussed around the bogong moth. See https://johntsquires.com/2019/01/30/learning-of-the-land-3-tuggeranong-queanbeyan-and-other-canberra-place-names/

So names are important. Names reveal much about those who bequeath the name. And names that have existed for millennia—indigenous names, the spirit names for the places—need to be honoured and remembers—and used! May that be one of the ways that we work towards reconciliation, this week, and long into the future.

https://johntsquires.com/2020/11/08/always-was-always-will-be-naidoc2020/