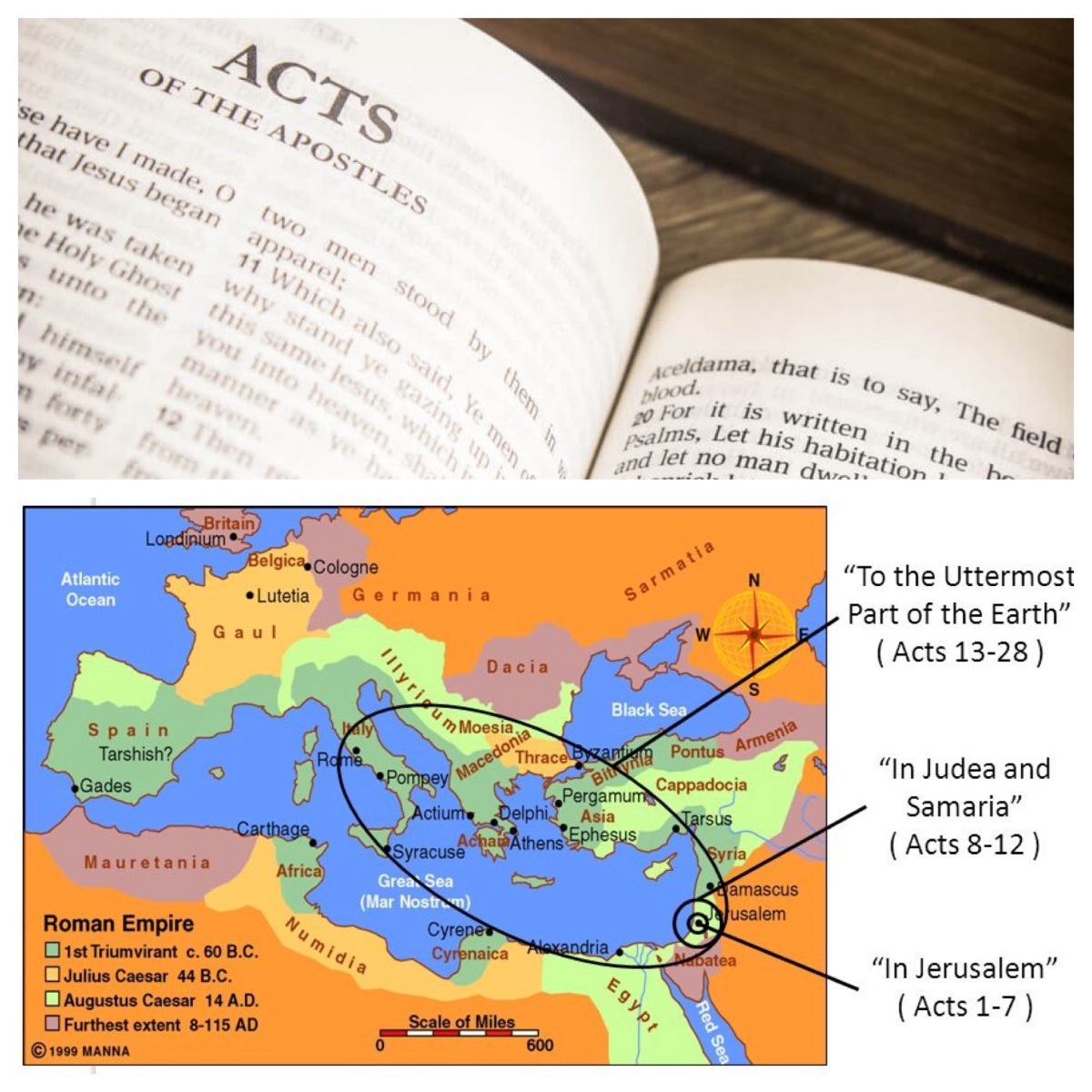

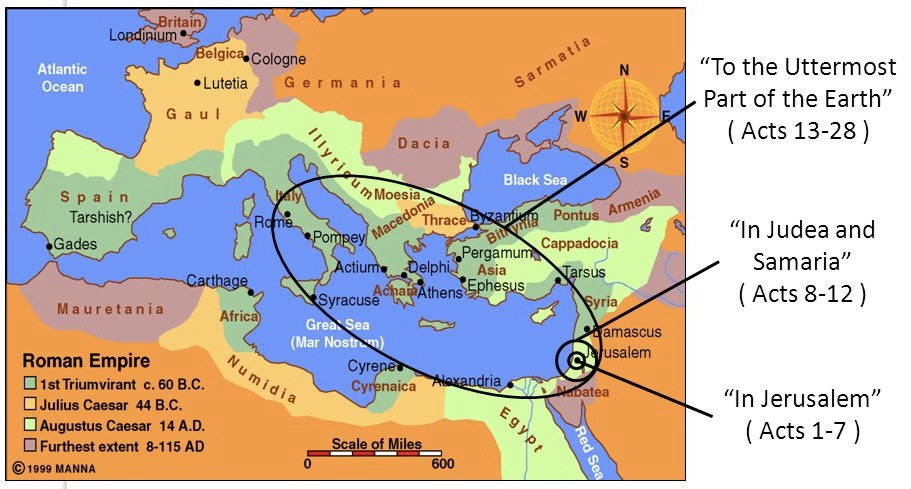

The passage from Acts that was proposed for last Sunday (Acts 17) and that proposed for this coming Sunday (Acts 18) come from the third main section of Acts, where the narrative tells of how Paul and various co-workers established messianic communities in towns throughout Asia Minor and around the Aegean Sea.

These communities contain many elements of the pattern of community life which has become evident in the earlier sections of Acts. In particular, this section consolidates the inclusive character of the community, for each newly-established assembly comprises Gentiles as well as Jews. In this way the section particularly builds on what has been established in the previous section.

In Corinth this week, as in Thessalonica last week, the tensions that exist between Jews and Gentiles in this community are evident. Paul had been travelling with Timothy and Silas, as we saw last week in Thessalonica; they had left him in Beroea (Acts 17:14) while he went on to Athens (17:16–34) and then to Corinth (18:1). Corinth was just 60km from Athens; it was a strategic trading city because of its two ports, one on each side of the isthmus. The old city had been sacked by the Romans in 146 BCE; they rebuilt it and declared it a colony in 44 BCE.

Whilst in Corinth, Paul meets with a new set of co-workers, Aquila and Priscilla (18:2). This married couple is well-known from Paul’s letters, where the mention of the female, in the shortened form, Prisca, in first place ahead of Aquila, is noteworthy (Rom 16:3; 2 Tim 4:19; see also 1 Cor 16:19). Luke notes that they are Jews who had recently moved from Italy to Corinth, as a result of the expulsion of Jews from Rome under Claudius (18:2); this probably took place in 49 CE (Suetonius, Claudius 25.4).

They work as tentmakers (18:3), an occupation often considered to indicate significant means (however, an alternative reading, that tentmakers were craftspeople of lower social status, is offered by some interpreters). This shared trade means that they can provide both hospitality and a place for Paul to carry out his trade whilst he is in Corinth. When Paul travels on, they accompany him to Syria (18:18) and Ephesus (18:19), where they remain while Paul continues on further; in Ephesus they instruct Apollos (18:26).

Paul’s familiar pattern (18:1–6) is evident as he argues in the synagogue on the sabbath, in an attempt to persuade his audience (18:4). As Paul here bears witness (18:5), a typical activity of his (20:21), he fulfils the promise made by Jesus (1:8), as also did Peter (2:32; 5:32). Paul’s message is the familiar refrain: “the Messiah, he is Jesus” (18:5; see 9:22; 17:3). Just as this claim provided the foundations for the community in Jerusalem (2:36), so in Corinth the declaration that Jesus is Messiah will form the basis for the Corinthian assembly.

Paul collaborated in the writing of many of his letters—of the seven agreed authentic letters, only two are written by Paul alone. The others are written in association with Timothy (2 Cor, Phil, 1 Thess and Phlm), Silvanus (1 Thess), and Sosthenes (1 Cor). It is an excerpt from this latter letter that the creators of the lectionary, in their wisdom, have offered us for this coming Sunday (1 Cor 1:10–18), alongside the short report (Acts 18:1–4) of Paul’s visit to Corinth.

Sosthenes and Paul tell the Corinthians that they write to “give thanks” (1 Thess 1:4) and also to “appeal to you” (1:10); and later, to “admonish you as my beloved children” (4:14). The constructive approach that they bring is made clear in the opening prayer of thanksgiving (1:4–9).

In the passage we hear this Sunday (1 Cor 1:10–18), there is an unequivocal statement about what undergirds the constructive intention that Sosthenes and Paul bring as they write. It is “the cross of Christ” (1:18) that shapes the discussion and directions that Paul will present to the believers in Corinth in the ensuing 16 chapters. (This letter is longer than all other Pauline letters, except for Romans—also 16 chapters in length.)

Acts reports that Paul left Corinth in company with Priscilla and Aquila (Acts 18:18), moving to Ephesus, in which city the letter to Corinth was written (1 Cor 16:8). There is no further mention of Sosthenes, although the co-authorship of 1 Corinthians might suggest that Sosthenes also left his home town of Corinth—at least for a time, to escape the persecution he had experienced there.

Sosthenes, like Crispus, would have been high-status in the Jewish community in Corinth. Sosthenes and Paul indicate that they have received other high-status visitors from Corinth, travelling to Ephesus: Stephanas, Fortunatus, and Achaicus (16:17), as well as “the people from Chloe” (1:11)—were they, perhaps, slaves from the household in which Chloe was patron? Female patrons, of course, were known at the time—witness Phoebe (Rom 16:1–2), and see the excellent overview of Marg Mowczko at https://margmowczko.com/new-testament-women-church-leaders/

So Paul and Sosthenes were well-informed as they write this letter to the Corinthians. There are problems aplenty in Corinth. In the few verses set for this coming Sunday, they write about division and the quarrels that have resulted. They plead for agreement and unity. They remind the Corinthians about baptism.

In subsequent chapters, they will range over a long list of matters, often introducing them with the formulaic “now concerning …” (7:1, 25; 8:1; 12:1; 16:1, 12). That formula may suggest they are responding to specific information brought by their visitors. It certainly points to vigorous discussions about a number of matters where there were divergent opinions amongst the Corinthians.

So, in verse 18, the last verse of the selection offered for this Sunday, Sosthenes and Paul sound out the key theme of this letter, which is about the cross of Christ: “foolishness to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God” (1 Cor 1:18). The verses immediately following develop this motif of the paradox inherent in the cross with rhetorical finesse.

Given the reference to an earlier letter to the Corinthians (1 Cor 5:9), there may already have been discussion of the cross of Christ—either in that letter, or in a presumed response from the Corinthians, or in personal discussions and sermons during the period that Paul and others were in Corinth. Acts 18 indicates that Paul was there for 18 months, along with Aquila and Priscilla, Silas and Timothy, as well Titus Justus, a godfearer and Crispus, the leader of the synagogue (archisynagogos), and also Sosthenes, also identified as a leader of the synagogue (archisynagogos) who was seized and beaten in the presence of Gallio, the proconsul (Acts 18:17). Was the cross the focus of any of his preaching during this 18 months? It seems quite a plausible speculation.

“The cross” is certainly a theme that was sounded by Paul in his preaching and his writing. He had written to the Galatians, “may I never boast of anything except the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ, by which the world has been crucified to me, and I to the world” (Gal 6:14).

He had written to the Philippians, urging them to “have the same mind” as Christ Jesus, who “humbled himself and became obedient to the point of death—even death on a cross” (Phil 2:8), and warning them that those who opposed Paul’s preaching were “enemies of the cross” (Phil 3:18).

He would later inform the Corinthians that he models his own ministry on that of Christ; “he was crucified in weakness, but lives by the power of God; for we are weak in him, but in dealing with you we will live with him by the power of God” (2 Cor 13:4)—just as he had told the Galatians that “I have been crucified with Christ; and it is no longer I who live, but it is Christ who lives in me” (Gal 2:19–20).

He would also later exhort the believers in Rome to see their baptism as the means by which they were linked with Jesus in his death and resurrection, instructing them that “our old self was crucified with him so that the body of sin might be destroyed, and we might no longer be enslaved to sin” (Rom 6:3–6). In the central theological argumentation of this important letter, Paul places the cross as the means by which the good news is known: “God proves his love for us in that while we still were sinners Christ died for us” (Rom 5:8).

He would remind them that “Christ died and lived again, so that he might be Lord of both the dead and the living” (Rom 14:9), and he deals with the conflict in Rome between weak and strong by proposing that the quarrelling parties follow the pattern established by Christ, who “did not please himself; but, as it is written, ‘The insults of those who insult you have fallen on me’” (Rom 15:3). The cross informed his instructions to the Romans for their daily living.

The same process is employed in the earlier letter to the Corinthians. The cross is the benchmark for understanding how believers are to behave, how they are to relate to one another, and how the community that they form is to be described. All of this is worked out in the first two chapters of the letter (1 Cor 1:18–31; 2:1–12).

There, Paul will remind the Corinthians that “we proclaim Christ crucified, a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles” (1:23), that “I decided to know nothing among you except Jesus Christ, and him crucified” (2:2), and that the paradoxical wisdom that is at the heart of the story of Jesus, “none of the rulers of this age understood this; for if they had, they would not have crucified the Lord of glory” (2:8).

For this passage, however, the message is focussed on the centrality of the cross, as the way that God (in Paul’s mind) has chosen to communicate with the people of his time.