The time is early in the morning – quiet, dark, peaceful; the same time of day as when we came to this place. The cast of characters is well-known; Mary Magdalene; Salome, Joanna, another Mary; we know these women. And the message is, likewise, a comforting, familiar refrain: The tomb is empty. He is not here. He is risen. In all that we have heard, we are on familiar ground.

It is most likely that each of us are also well-acquainted with the flow of the story—the women come, bearing their spices, to anoint the body; the stone is found rolled away; the tomb is seen to have no body; and the message is delivered in short, succinct phrases: The tomb is empty. He is not here. He is risen.

The place may be a little unusual, in our way of thinking: it is a tomb, carved out of the rock, large enough to enable a number of adults to be buried together. As people of Anglo heritage, we are used to individual plots, dug deep into the ground, where one person, or maybe a married couple, are laid to rest.

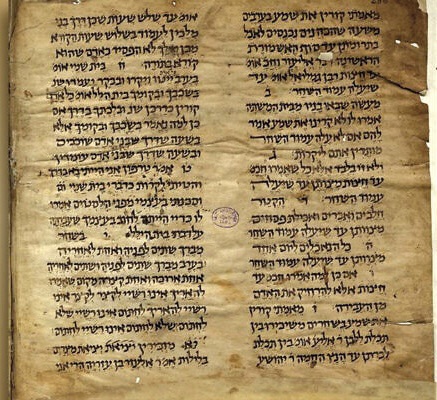

But this is different: it is a large cavity in the side of a rockface, carved out to enable space for a number of adults to enter; space enough for generations of a family to be laid to rest within the one very large tomb. This practice can be seen in phrases, frequently used in mentioning the Patriarchs and David, in Hebrew Scriptures: when such an eminent person died, he would be “gathered unto his fathers,” “sleeping with his fathers,” or “gathered unto his people.”

But these aren’t just euphemisms for death—like we say, ‘passed away’, or ‘went to their eternal rest’; no, this was a literal, physical description of what was done with the bodies of deceased people in ancient times: they were placed in the family tomb, alongside the resting-places of relatives and ancestors.

So the physical location, and the cultural custom, is rather unfamiliar to us today. But the rest of the story, we reassure ourselves, runs along familiar lines, following the well-trodden pathway.

Or does it?

Step back from the empty tomb; walk away, for a moment, from the Easter narrative. Consider the broad sweep of our Christian faith; the overarching drama of our Christian lives.

What do we expect to be central and essential to our Christian faith? What is it that we anticipate finding at the very heart of our faith? How does faith function in the lives of people today, in or time, amidst the stresses and pressures of 21st century living?

Psychologists—those who study the human mind—tell us that people in our times are more likely than ever before to be depressed. Our deepest yearning is to be happy, to feel appreciated, to have assurance that we are valued, that we are loved.

Sociologists—those who study human societies—tell us that people in our times feel disconnected, isolated, and cut off from one another. Our common yearning is to be a part of a group, to feel that we belong. We need to know that others need us.

What this analysis often leads to, is a sense that people today are looking for certainty—we want to be grounded in a group, we want to be part of the tribe, we want to be loved and appreciated, we want to know the assurance of the absolute.

And faith—Christian faith, or indeed any form of faith—can then be offered as the way for people, in their fear and anxiety, in their loneliness and uncertainty—faith can be offered as an answer to these ills. ‘Just take this pill (this pill of absolute faith) and you will be right.’ ‘Just switch your allegiance in one fell swoop, and all will be different.’

Let me invite you to think about these issues in the light of the story which we have heard retold today. For as we encounter and engage with the unfamiliar dimensions of the story, we will find a rather different response to our situation emerging from the interplay.

There are two striking and unfamiliar elements in the story of the empty tomb. The first has to do with who is there. And the second has to do with who is NOT there.

Who is there, that early morning, in the tomb where the body of Jesus had been laid, just a few days earlier? Who are the ones who see, and hear, and experience for themselves, the jarring reality of that early morning encounter?

In a society so dominated by males—male priests, male scribes, male teachers of the Law, male heads of each household—is it not striking and jarring that the great news of Easter is entrusted, first of all, and in all its fullness, to a group of women?

Women—who come to perform their traditional female role, of anointing the freshly-interred body. Women—who come in subservience and devotion, to enact the ritual which has been set aside for them to undertake, as befits their allocated role in society. Women—who, if the traditional pattern is to be followed, will come, unwind the covering on the body, anoint the body with spices, reroll the covering and replace the body, and reverently leave the tomb.

But these women are unable to carry out the male-determined ritual for the body of the recently deceased. The familiar pattern is interrupted; the servant role is removed; and it is these women to whom the striking news of Easter is given.

It is to these women that the responsibility is given, for declaring that the body of Jesus is no longer gripped by death. It is to these women that the role of being the first, the primary, witnesses, to the interrupting action of God: the one who was dead, Jesus, our Master, is no longer here.

The tomb is empty. He is not here. He is risen.

God is now working in ways that challenge, disturb, and overturn the well-worn, familiar, traditional patterns of society. The women cannot carry out the duties and responsibilities that they have long been given. The women, now, are to be witnesses to what God has done. They are to return and tell the men—the apostles, the pillars, the chosen ones—what God has been doing. He is not here. He is risen.

It is the women, and not the men, as expected, who are the ones to break the news: He is not here. He is risen. It is the women who become the first evangelists, the first to proclaim the good news of God. It is the women who become apostles, even to the apostles, the men waiting in the city, unaware of what has occurred at the tomb, and unacquainted with what God has been doing through Jesus. He is not here. He is risen.

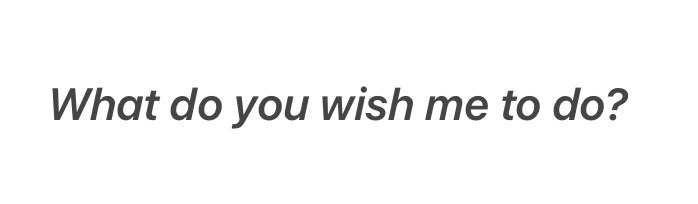

If the first striking feature of this story is, who IS here; then the second arresting aspect, is who is NOT here. This is a story about Jesus, in which Jesus does not appear.

This is an account of the most dramatic and significant moment in the whole narrative about Jesus—but there is no Jesus to be seen! No Jesus to be touched!

No Jesus with whom to talk! No Jesus to stand, centre-stage, as demonstration of the realities of how God is now at work.

So here is the conundrum: this is the precise moment in the story when God acts in a new and surprising way. This is the pivot point upon which the whole of the narrative turns.

And yet, at the heart of the story, there is—nothing! No central character. No resurrected Jesus, shining forth God’s glory for all to see. No dramatic, booming voice from the heavens, declaring the risen Jesus as the Lord of all. All that we have, are the words of the young men: He is not here. He is risen. There is nothing, but a startling absence, precisely at the moment when we expect a dramatic presence.

In my mind, this paradoxical turnaround is highly significant, hugely important. At the centre of our faith, there is an enticing invitation—to explore, to ponder, to imagine, to wonder.

There is no clear, black-and white, unequivocal proof. There is no definitive dogmatic assertion, no unquestionable, unambiguous deed, no unarguable proclamation—no resurrected Jesus standing in the tomb. There are simply the women, stunned; and the young men, explaining: He is not here. He is risen.

So, at the heart of the Easter story, we find absence; mystery; the glimpse of a possibility; the wisp of a wondering; the beginnings of a pondering: ‘how can this be’; ‘what does this mean?’; ‘what do we do next?’; ‘where is this all leading?’.

And in my mind, this central absence, at the heart of the story, reminds us of the essence of our faith. In our faith, we have no clearcut, unquestionable dogma; we have no unchangeable given, no unarguable declaration. We have no absolute assurance, no certainty set in concrete.

Rather, we have an invitation to walk the way of faith, with openness; an invitation to delight in the mysteries which God unravels before our eyes, in our own lives; an invitation to search, to explore, to ponder; and perhaps then, to encounter, to marvel, and to rejoice.

He is not here. He is risen. So let us enter into the mystery, the enticement, and the joy, of faith!