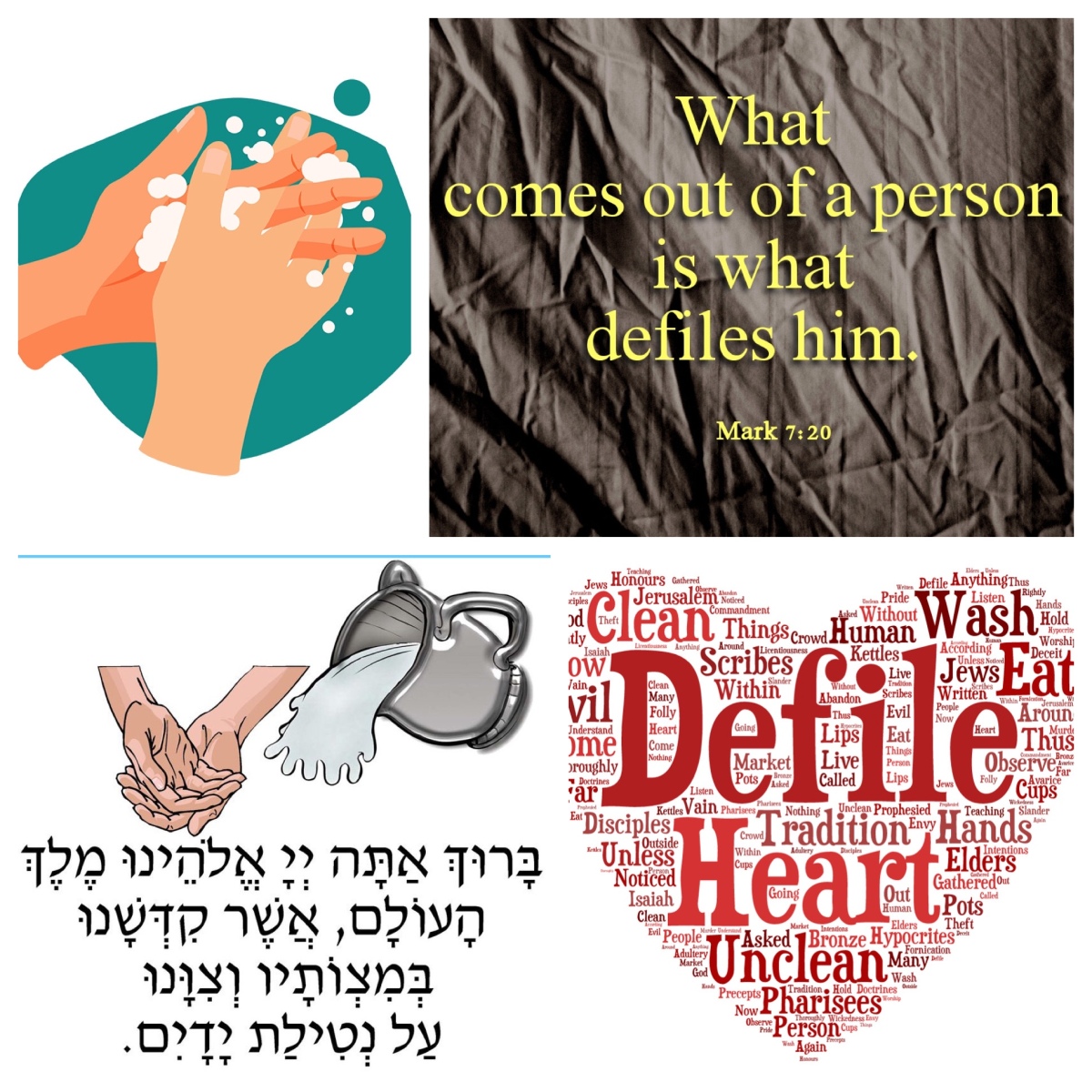

Wash your hands. It’s a simple instruction.

Wash your hands! It’s guidance that has been particularly pertinent over the past 18 months, as we have grappled with the dangers of transmitting a novel coronavirus which has been responsible for a global pandemic. Wash your hands—carefully, thoroughly, singing “Happy birthday to you” through twice.

So the opening verses of the Gospel passage offered by the lectionary for this coming Sunday sounds quite relevant: “when the Pharisees and some of the scribes who had come from Jerusalem gathered around him, they noticed that some of his disciples were eating with defiled hands, that is, without washing them” (Mark 7:1–2). Eating without washing hands, to us, is not a wise thing. Surely, the same applies to the disciples of Jesus, back 2,000 years ago?

Well, it’s not that simple. It’s not just a matter of washing your hands, using soap and warm water, for 30 seconds—not in the biblical text. It’s a more complex and nuanced matter, in this biblical story. The author of this Gospel makes it quite clear that it’s not just a matter of “wash your hands”.

The opening phrase identifies that it was the Pharisees and some scribes who noticed what the disciples were (or rather, weren’t) doing.

That’s significant, because they were the people amongst the Jews who attends carefully to all the details of what the Law required the people of Israel to do. The scribes and the Pharisees devoted their lives to teaching and explaining each of the 613 commandments and ordinances that were included within the books of Torah (the books of the Law—the first five books of Hebrew Scriptures).

So they knew that washing hands before eating was a part of life that included many details. There were quite a number of factors involved in preparing to eat. It was a complex matter—as, indeed, was attending to each of those 613 laws.

This complexity is signalled in a significant aside as the story is told (marked by parentheses in our Bibles), as we read that “the Pharisees, and all the Jews, do not eat unless they thoroughly wash their hands, thus observing the tradition of the elders; they do not eat anything from the market unless they wash it; and there are also many other traditions that they observe, the washing of cups, pots, and bronze kettles” (Mark 7:3–4).

In terms of the “many traditions” that the Pharisees valued, the washing of hands included a number of factors. How much water would be sufficient to cleanse the hands? From what vessel can the water be poured onto the hands? How much of each hand should be washed when performing this action? What water is acceptable, and what will not be acceptable? Who is required to perform this action? Is everyone required to do this? What might make the handwashing ineffective?

Now, before we come down heavily on the scribes and the Pharisees, and accuse them of legalism and of being fixated on details and of placing heavy burdens on the people, let’s remember the ways that our own court system operates today. We have laws, covering all manner of situations, addressing many different actions. Each law has a number of sections and subsections in the relevant legislation.

Then each magistrate or judge applies that law to the specific situation before the court. Case law develops, providing precedents for this situation of that situation. Before you know it, you are looking at a whole bookcase full of documentation that is required to be known, before actions can be assessed under the law.

The Pharisees and the scribes were doing the same. They were exploring all the options, all the possibilities, in applying the law. And they were teaching the people, instructing them in how to attend to the commandments and ordinances that were given by God to the people through Moses—and through the line of interpreters which followed on over the ensuing centuries.

Eventually, the accumulation of explorations and considerations about these commandments and ordinances were written down—some centuries after the time of Jesus—in a document which we know as the Mishnah, a Hebrew word which comes from a root word meaning “repetition”. The Mishnah contains the teachings of rabbis from centuries past, which were learnt by male Jewish students by study and repetition.

One of the tractates in the Mishnah is entitled Yadaim, which means “hands”. It is the eleventh of twelve tractates in the sixth order of the Mishnah, which is entitled Tohoroth, meaning “purities”. The whole section deals with the distinctions between clean and unclean, and provides guidance on how to maintain the state of purity, or being clean.

of discussions about the commandments and ordinances

made under Rabbi Judah ha-Nazi in around 320CE

Yadaim provides a detailed discussion of washing hands prior to eating, and canvasses precisely those questions that I posed above. It is important to note, however, that the matter of washing hands before eating is not simply (as we would understand it) a ritual which is designed to remove germs and ensure that no infections occur. It is not about physiological cleanliness and medical health. Rather, it is about holiness, about being clean before God, about being in a right state when sharing in a meal.

The commandment to wash hands does not actually appear in the Hebrew Scriptures. There are instructions to wash hands prior to various actions, involving a person with a discharge (Lev 15:11) and in sacrificing a heifer in relation to an unsolved murder (Deut 21:6). There is also an instruction for the priests to wash their hands and their feet with water from the bronze basin before they approach the altar of sacrifice (Exod 30:17–21).

However, the practice of washing hands before praying is attested in a document some two hundred years before the time of Jesus. The Letter of Aristeas (written around 150 BCE) reports that the 72 translators of the Septuagint, “following the custom of all the Jews, washed their hands in the sea in the course of their prayer to God” (Aristeas 305). Some decades later, one of the Sibylline Oracles states that “at dawn, they [the Jews] lift up their holy arms toward heaven, from their beds, always sanctifying their flesh with water” (Sib. Or. 3.591–93).

a later rabbinic development beyond the time of Jesus

The argument, then, for the development of the practice that the scribes and Pharisees advocated, is that a faithful Jew would pray before eating—a prayer of blessing, in gratitude for the food—and thus would wash their hands before praying. Thus, always washing hands before eating would have been commonplace by the time of Jesus.

It is often argued that what the Pharisees and scribes have done, is to extrapolate from the requirement placed upon the priests before they enter the presence of God (Exodus 30) to apply the principle to all faithful Jews as they approach the meal, a time of fellowship with God (Mishnah tractate Yadaim).

This is not an unreasonable line of argument. The Pharisees and the scribes did precisely this over and over again, with regard to all manner of actions prescribed for the priests. The enterprise of the Pharisees was to take the instructions placed upon the priests in Jerusalem as they conducted their daily rituals in the Temple, as guidelines for the way that faithful Jewish people in towns and villages were to act as they went about their daily business. The Law, in their view, was not simply for the elites in one place; the Law was God’s instruction to all the people, on how to be faithful to God, reverent and devout, in every aspect of their lives.

The Law was a gift that was provided by God, to ensure that the people of Israel maintained their state of being as “a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a people for [God’s] own possession” (1 Peter 2:9), in obedience to God’s declaration, “you shall be holy, for I am holy” (Lev 11:44, cited at 1 Peter 1:16).

To be consistently and thoroughly holy—set apart, consecrated, dedicated to God—means that each mundane action in daily life is to be carried out in ways which reflect the faith of the people, their ongoing commitment to the covenant relationship with God. They were to live in a way that invited God into every aspect of life—including, in this instance, preparations for eating at table. Washing hands before praying before eating ensured that each meal was seen as a holy action performed by a holy people.

However: Jesus appears to be arguing against this, when he declares, “you leave the commandment of God and hold to human traditions” (Mark 7:8). What do we make of this direct and clear negation of the Pharisees’ position?

The first factor to note is that whenever Jesus engages in debate and discussion with the scribes and the Pharisees, he is actually engaging them on their home ground, undertaking the very activity that they took part in each and every day. Debating the details of Torah, exploring alternate interpretations, posing options for application, was the very essence of the work of the Pharisees. Quoting one passage of scripture as counterpoint to another passage already cited (as Jesus does in Mark 7:6–13) was a standard element in such debates.

Exaggeration and over-statement was also integral to these debates, as the participants pushed and probed the case put forward by their opponents, contesting the claims made and advancing counter-claims with gusto. Jesus is doing precisely this in his interactions with the scribes and Pharisees. He most likely was quite assertive—it was the style of such debates—and could well have been aggressive and controversial in such debates.

See https://asiasociety.org/countries/religions-philosophies/art-debate-jewish-style

However, a second factor is that this narrative is not an eye-witness report, direct from the time precisely when the encounter occurred. Rather, it is a narrative created in the oral traditions of the early church, not written down into the form we have it until some decades after the event. This context is important.

The way that the canonical Gospels portray disputes between Jesus and other Jewish teachers of the Law reflects the context in which tensions between Jews in the synagogues and Messianic Jews (followers of Jesus) had become heightened. Portraying the interaction as an aggressive, polemical encounter reflects the life setting within which the narrative is written. The encounter has most likely been exaggerated and intensified because of the context in which the written narrative was shaped.

After all, once the early followers of Jesus (who were overwhelmingly Jews) had made the decision that Jesus was in fact their long-awaited Messiah, and then articulated this decision within their local communities of faith (the Jewish synagogues where they participated in faith-based activities), they were criticised, corrected, disputed, denounced, and eventually, so it seems, expelled from all synagogue involvement. It was an increasingly unhappy environment. So, portraying the interaction between Jesus and the Pharisees in Mark 7 as an aggressive, polemical encounter reflects the life setting within which the narrative is written. The encounter has most likely been exaggerated and intensified.

The conclusion that Jesus reaches, “what comes out of a person is what defiles him” (7:20; see also verses 15 and 23) does not overturn the laws of purity, taught and advocated by the scribes and the Pharisees. Rather, it is the distinctive contribution to the debate about purity that Jesus makes; that our morality is shaped and influenced by what we have internalised, by the very ways that we live each and every day, by the principles that guide and even determine our actions. And that, after all, is what the scribes and the Pharisees were seeking to inculcate amongst the people of the covenant. How we live influences what we believe, and what we believe shapes how we act.

So: wash your hands! And make sure that all that you do reflects all that you believe and hold dear.

*****

See also https://johntsquires.com/2021/08/24/stretching-the-boundaries-of-the-people-of-god-mark-7-pentecost-14b-15b/ and https://johntsquires.com/2019/10/21/in-defence-of-the-pharisees-on-humility-and-righteousness-luke-18/