After the scene in the synagogue, which we heard last Sunday, the lectionary offers us a collection of scenes (Mark 1:29–39) for the fifth Sunday after the Epiphany. These scenes are part of the rapid sequence of events that Mark tells, to introduce Jesus, the main character of his narrative over the ensuing chapters.

We have already had the announcement from John about “one more powerful than I” (1:2–8) and the striking moment when Jesus of Nazareth was declared to be the beloved Son, anointed by the Spirit, equipped for his role of proclaiming the kingdom of God (1:9–11).

See https://johntsquires.com/2020/12/01/advent-two-the-more-powerful-one-who-is-coming-mark-1/

Then follows a period of testing in the wilderness (1:12–13) and a succinct summation of the message of Jesus; just four short, snappy phrases: “the time is fulfilled, the kingdom of God has come near, repent, believe in the good news” (1:14-15). See https://johntsquires.com/2020/11/24/the-kingdom-is-at-hand-so-follow-me-the-gospel-according-to-mark/

This summary is followed by two compressed accounts, told in formulaic exactitude, in which Jesus calls four of his key followers, brothers Simon and Andrew (“follow me; they left their nets, and followed him”), and then brothers James and John (“he called them; they left their father, and followed him” (1:16-20). See https://johntsquires.com/2024/01/16/fishing-for-people-not-quite-what-you-think-mark-1-epiphany-3b/

These two call narratives establish the nature of the movement that Jesus was initiating. He sets out a call to all four brothers; an exclamation, to which they must respond: “follow me!” The call invites a specific, tangible, and radical response: “leave everything”. And both encounters result in a new, binding commitment to Jesus: they “followed him”. The same pattern repeats with Levi in 2:14, and then with others (2:15; 8:34-36; 15:41). A rich young man comes to the brink, but then pulls away at the last moment (10:21).

Ched Myers offers a good exploration of how this scene establishes the dynamic of radical discipleship which permeates Mark’s Gospel, at https://inquiries2015.files.wordpress.com/2002/08/02-1-pc-mark-invitation-to-discipleship-in-ringehoward-brook-discipleship-anthology.pdf

Myers parallels this call scene with a later scene (8:22-9:13) in the following way: “Each prologue introduces the essential symbols, characters, and plot complications of the respective ‘books’. Each takes place in the context of ‘the Way’ (1:2f; 8:27), and discusses the relationship between Jesus and John-as-Elijah (1:6; 8:28). In both prologues, Jesus is confirmed as the anointed one by the divine voice (1:11; 9:7) in conjunction with symbolism drawn from the Exodus tradition (wilderness, 1:2,13; mountain, 9:2).

“Each articulates a call to discipleship (1:16-20; 8:34-36) specifically in regard to Peter, James, and John (1: 16,19; 9:2). In Book I Jesus calls disciples to follow him in overturning the structures of the present social order. But because these disciples’ understanding is suspect, Jesus must in the prologue of Book Il extend a ‘second’ call to follow, in which he introduces the central symbol for the rest of the narrative: the cross.”

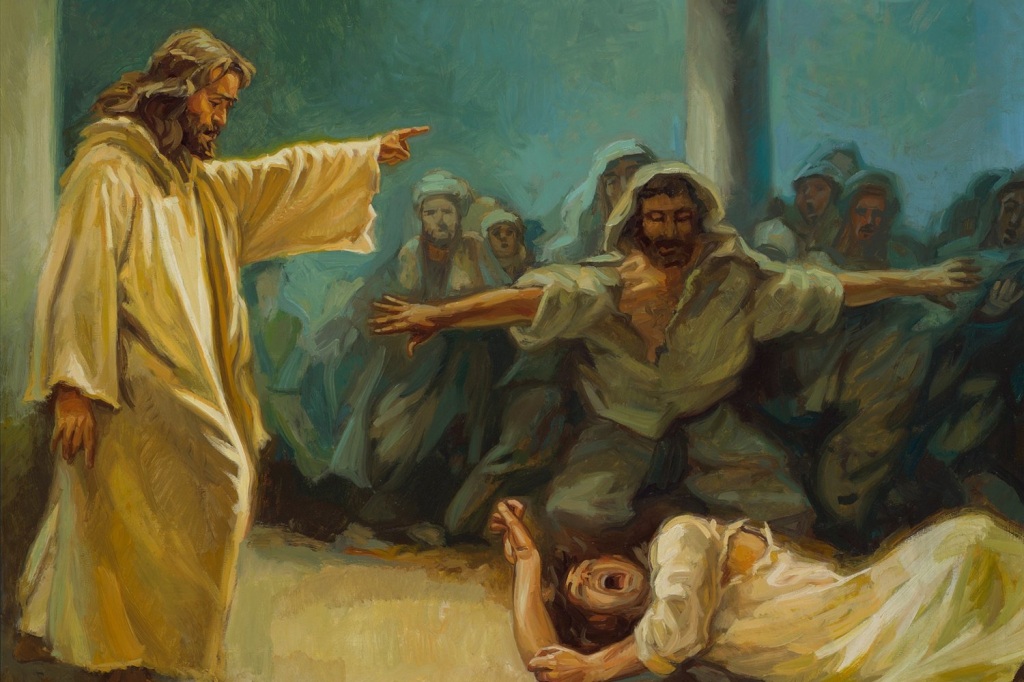

After these stories of announcement and call to follow, there comes a scene in a synagogue, revealing the authority that Jesus had, in calling people, to command “the unclean spirit, convulsing him and crying with a loud voice, [to] come out of him” (1:21–28). See

*****

The section of this chapter offered for this coming Sunday (1:29–39) begins with a pair of complementary scenes—the first set in the hustle and bustle of the village, where Jesus heals the sick and casts out more demons (1:29–34); the second an early morning start, where Jesus prays “in a deserted place” (1:35–37). This contrast is deliberate, and instructive. Both settings are vital for his project of radical discipleship.

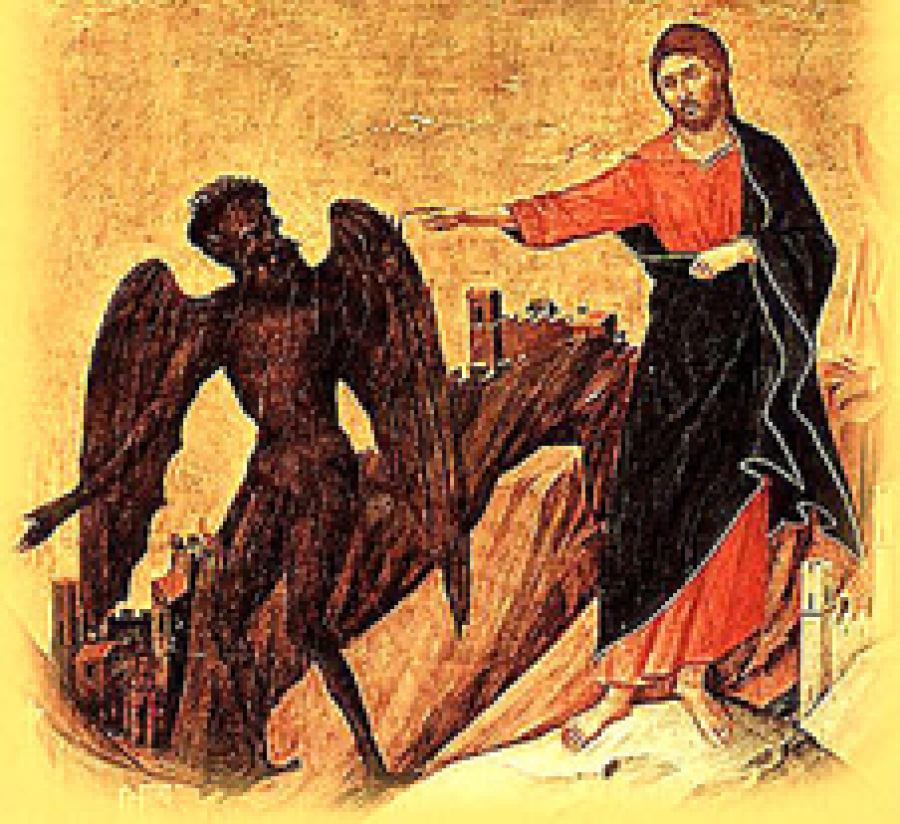

This latter scene evokes the earlier scene, immediately after the public dunking of Jesus in the Jordan river (1:9–11), when Jesus spends a highly symbolic forty days “in the wilderness” (1:12–13). Although it was the Spirit which drove him into wilderness (1:12), it was Satan who tested Jesus during this period (1:13). And that seminal encounter sits alongside the first public declaration of Jesus as “beloved Son”, made over the waters of the Jordan (1:11). See Forty days, led by the Spirit: Jesus in the wilderness (Mark 1; Lent 1B)

The author then provides a characteristic summation of the activity that Jesus was called to do: “he went throughout Galilee, proclaiming the message in their synagogues and casting out demons” (1:38–39). Subsequent summaries in this vein appear a number of times in the ensuing narrative (3:7–8, 4:33–34, 6:12–13, 6:56, 10:1). The opening chapter thus sets the pattern of behaviour by Jesus.

A final, intensely emotional scene brings this substantial opening sequence to a close. In this final scene of chapter 1, Jesus is approached by a leper, seeking to be “made clean” (1:40–42). The way Jesus responds to this need is striking: what the NRSV translates as “moved with pity” is actually better rendered as “being totally consumed by deep-seated compassion” (1:41). An alternative textual variation renders the emotions of Jesus more sparsely: “and being indignant”.

The command to adhere to the law by bringing a sacrificial offering to the priests for his cleaning (as any teacher of Jewish Torah would advocate—Lev 14) is, strikingly, expressed in the typical manner of a wild magic healer; the NRSV translation, “sternly warning him”, is better expressed as “snorting like a horse”—the use of striking, dramatic language being a characteristic feature of ancient healers (1:43–44).

The final scene collects all the activity of the opening chapter into the bustling energy of the swarming public square. Jesus can no longer remain isolated or removed; “people came to him from every quarter” (1:45). However, this passage, along with other sections of chapter 2, appears in the lectionary only in a year when Easter is later and thus the season of Epiphany is extended by further weeks. Because of the early date of Easter this year (2024), we will not be reading and reflecting on it this year.

Perhaps the key takeaway for us, today, from this collection of scenes, is in verse 38: “let us go on to the neighboring towns, so that I may proclaim the message there also; for that is what I came out to do.” The Jesus of Mark is an energetic, passionately committed person, travelling relentlessly, proclaiming his message of the coming kingdom with an intensity, engaging with people with compassion, focussed on achieving his goal. That’s the invitation that stands before us this Sunday: how do we respond?