This year in the calendar of the church is what is called Year B. That means that, for the most part, the Gospel reading will be drawn from the earliest, and shortest, account of the life of Jesus that we have in our Bibles: the work that starts, the beginning of the good news of Jesus, which we call, by tradition, the Gospel according to Mark. (In Year A, we have passages from Matthew; in Year C, selections from Luke.)

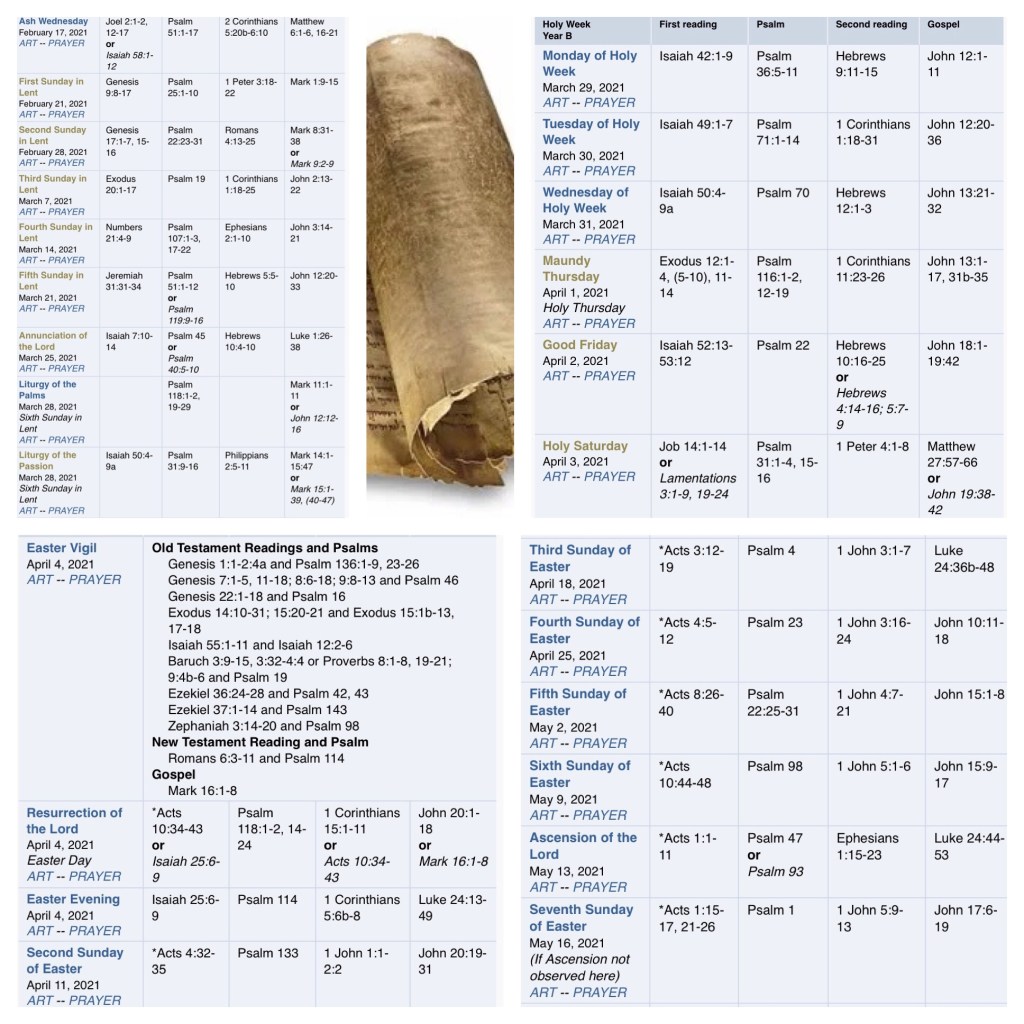

Except that, with one notable exception, Sunday readings from some weeks ago, right through until Pentecost (this year, falling on 23 May) are not drawn from Mark! Where has Mark gone?

We are in the midst of readings, during Lent, from John (7—28 March); then there will be readings, during Holy Week, once again from John (29 March to 2 April). We will hear an excerpt from Matthew on Holy Saturday (3 April); stories from John and Luke on Easter Sunday (4 April); and then another string of passages from John during the season of Easter (11 April to 16 May).

Pentecost Sunday designates part of John 15, and then Trinity Sunday offers John 3. Stories from Mark are nowhere to be seen. Where has Mark gone?

(To be fair: the lectionary has to do this, if it is to provide a good selection from the Gospel according to John, as that Gospel doesn’t have it’s own year. So its passages are spliced throughout Lent and Easter in all three years.)

The one exception to this Mark-drought is Sunday 28 March. If you celebrate this as Palm Sunday, then a passage from Mark is offered (Mark 11:1-11)—although an alternative from John is provided! If you celebrate this as Passion Sunday, then the whole passion narrative in Mark’s Gospel is offered (Mark 14:1—15:47)—with an alternative being a shorter excerpt from that extended narrative (Mark 15:1-39, with 40-47 as an option).

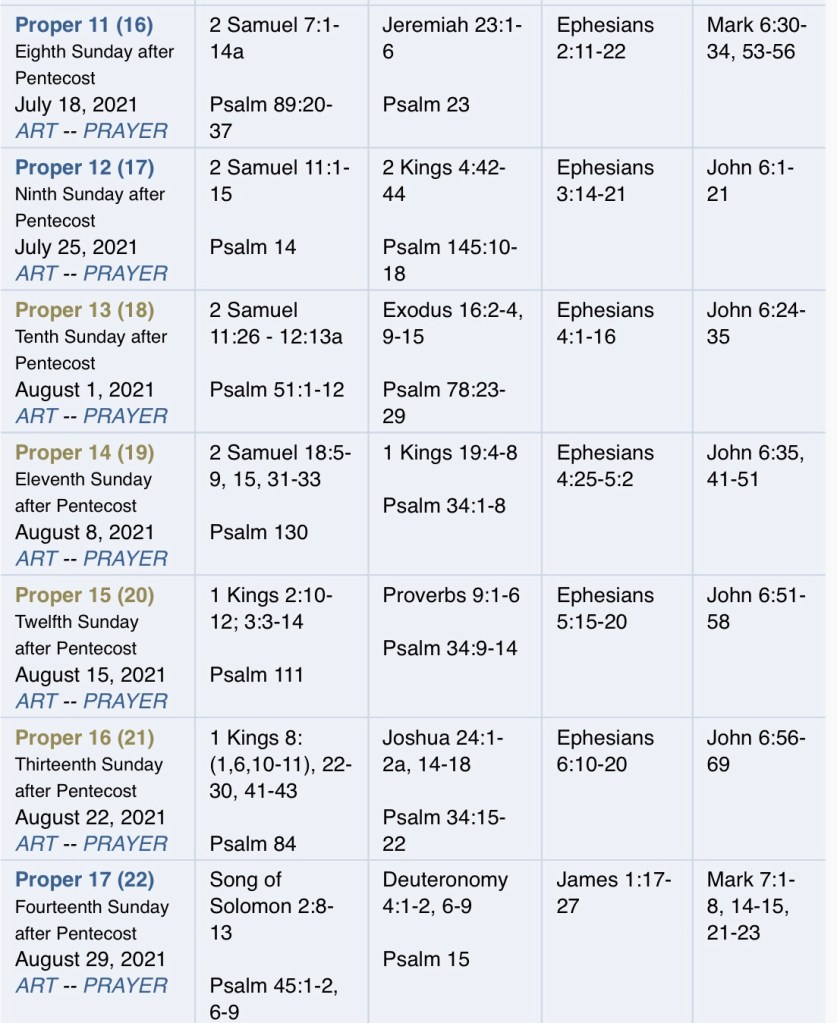

So it will not be until June before we return to the weekly diet of stories from the beginning of the good news—6 June, to be precise, where we pick up the narrative with Jesus in his home town, surrounded (as is usual in this Gospel) by a crowd, being criticised by his family and accused by some Jerusalem scribes (Mark 3:20-35). Hardly a propitious place to rejoin this early Gospel story.

(And even then, there is a five-week interruption in August, when we hear all bar a handful of the 71 verses in John 6 !)

So: I plan on offering a series of blogs leading up to Passion Sunday (28 March) which deals with elements in the story that Mark first told—at least in written form—about what transpired in Jerusalem, at Passover, during the governorship of Pontius Pilate.

But first, some general comments about this earliest and shortest Gospel.

*****

We know that Jesus did not write an account of his life; in fact, we know of nothing enduring that he wrote. In the New Testament, we have four accounts which relate how Jesus called followers to travelled with him around Galilee, and then to Jerusalem, where they witnessed his arrest, trials, crucifixion, and burial of their leader. Subsequently, they attested that he had been raised from the dead and had appeared to them to commission them for their ongoing task. We have four of these accounts. They each have their own distinctive features.

The story of Jesus is told, first, in the beginning of the good news of Jesus the chosen one, the shortest account. We know this, because of Church tradition, as the gospel according to Mark. This work, it is clear, forms the primary source for two subsequent accounts of Jesus: the book of origins of Jesus, chosen one (the gospel according to Matthew) and an orderly account of the things fulfilled amongst us (the gospel according to Luke).

In this earliest written account of Jesus, we find stories told by Jesus, and stories told about Jesus, which had already been circulating in oral form for some decades. It is likely that some of these stories had already come together in short collections.

The distinctive contribution of this collated story was twofold. First, it places side-by-side a number of different traditions, or collections of stories, about Jesus. Second, these stories are arranged in a dramatic way, beginning with the stories about Jesus in his native area of Galilee, and culminating in the account of Jesus’ passion in Jerusalem.

This work thus provides a much fuller ‘story of Jesus’ than any of the individual oral stories about him. Isolated incidents are placed within a larger context. Individual sayings and deeds of Jesus are grouped together with similar sayings or deeds. Episodes are linked together to form a coherent account of who Jesus was and what it meant to follow his way.

There are two main parts this account of the beginning of the good news of Jesus the chosen one: telling stories about Jesus in Galilee and on his journey to Jerusalem (Mark 1–10) and then telling what happened to Jesus in Jerusalem (Mark 11–16).

But this account of Jesus is more than just a compilation of existing stories. It is infused with vigour and intensity. The story moves from one incident to the next; yet the whole Gospel is a carefully-crafted piece of literature. A sense of drama runs through the Gospel. You might be forgiven for thinking that this is a movie script!

*****

Central to this narrative is a story of conflict. Jesus is set into conflict with the authorities from early on. It is hinted at in the claim that Jesus speaks blasphemy (2:7), and then is revealed in full in the plot that is initiated (3:6). The shadow of destruction hangs over Jesus from the beginnings of his activity.

The tension mounts, from the early days in Galilee, towards the events that will take place in Jerusalem. His own family called him crazy (3:21), the people of his own town took offense at what he was preaching (6:3), and even his closest disciples seemed unable to grasp what he was teaching them (see 8:21; 9:33; 10:35–40).

The popularity of Jesus as he entered Jerusalem was fleeting, even though he acquitted himself so well in arguments with the leaders in Jerusalem (11:27–12:40). His actions in the Temple forecourt were controversial (11:15-17) and it is clear that this incident raised opposition to him to a high level (11:18). The final teachings he gave his disciples begin with a prediction of the destruction of the Temple before recounting the apocalyptic woes that are in store (13:3–37).

The plot hatched by the authorities (12:12; 14:1-2) led them to stir up the crowd to call for his death. Jesus was betrayed by one of his closest followers (14:10, 43-46), all knowledge of him was denied by another (14:30; 14:66-72), and all abandoned him at his point of need (14:50). The tragic climax of Jesus’ death is a scene of utter abandonment: “my God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (15:34). Only some—a group of faithful women—watched from afar (15:40) before they came to provide an honourable burial for the man who was condemned and dishonoured (16:1)—but precisely there, a surprise awaits them (16:2-7).

*****

Yet the account found in the beginning of the good news is still more than a dramatic account of a tragic death; for this work appears to be a kind of political manifesto, advocating the way of Jesus in a situation of deep tension and widespread conflict. The whole Gospel conveys the significance of Jesus and his message about the kingdom: “the time is near!” (1:15).

This story reveals the key fact that faithful discipleship will mean enduring suffering, as Jesus did. He writes to help believers understand what it means to follow Jesus and to take up the cross (8:34). These were potent words in the Roman Empire; death by crucifixion was the fate in store for criminals, especially those engaged in any political activities which the Roman authorities perceived to be a threat to the peace of the Empire.

Jesus’ injunction to “take up your cross” was advice which was loaded with danger. Was he advocating resistance against an oppressive Roman rule? The story which is told in this Gospel addresses issues which were pressing on the lives of those who told it, read it, and heard it.

Almost all of this work, the beginning of the good news, appears in basically the same order, in the two following accounts—the orderly account of the things that have been fulfilled among us and the book of origins of Jesus, chosen one. (We know these works as the Gospel according to Luke, and the Gospel according to Matthew.)

Both of these accounts expand the story, incorporating additional material—some is found in both accounts, other stories are recounted in one or the other of the orderly account and the book of origins. So the contribution made by the beginning of the good news is significant, and enduring.

See also https://johntsquires.com/2021/03/20/2-mark-collector-of-stories-author-of-the-passion-narrative/

3 Mark: placing suffering and death at the heart of the Gospel