A sermon by the Rev. Elizabeth Raine, preached at Tuggeranong Uniting Church on Sunday 31 October 2021.

*****

The book of Ruth stands as an island of peace and goodwill in the middle of a sea of wars, treachery, unfaithfulness and violence, as characterised by the preceeding book of Judges, and the following books of Kings and Samuel which follow.

The central characters appear to care for each other, the community generally acts well towards each other, and God’s providence is made available to the most vulnerable in society. It tells the story of a remarkable woman, a foreigner who gave up everything to devote herself to her Israelite mother-in-law Naomi.

The author also has a good sense of humour. The names of Mahlon and Chilion, the two sons that die, which in the Hebrew mean “sickness” and “consumption” respectively. Naomi’s home city, Bethlehem, literally means “house of bread”. So we find at the start that Bethlehem, the “house of bread” was in the grip of a famine, and that Naomi’s husband has to go to Moab, a land where the people are specifically excluded from the congregation of Israel because they refused to give bread to the Israelites fleeing Egpyt.

So Bethlehem, the house of bread, is starving its people, and the land of Moab where food was withheld from the Israelites, now has plenty to share with them. This reversal of the expected puts the reader on notice that this is no ordinary book and no straightforward story.

Although the story is set “in the days when the judges ruled” (ca. 1200-1025 BCE), the date of Ruth’s composition is probably much later. The story’s frequent reminders that its heroine is not an Israelite provides the best clue, and the storyteller is suggesting that Boaz’s gracious treatment of a Moabite woman in this way is unusual. This insistence on an inclusive attitude toward foreigners suggests a composition date in the fifth century BCE, when the issue of intermarriage between the Israelites and non-Israelites had become extremely controversial.

This short story therefore is composed to remind a nationalistic and post-exilic people who are keen on eliminating “foreigners” and people of mixed heritage that their most fondly remembered king, David, was the great-grandson of a Moabite woman.

Ruth 1

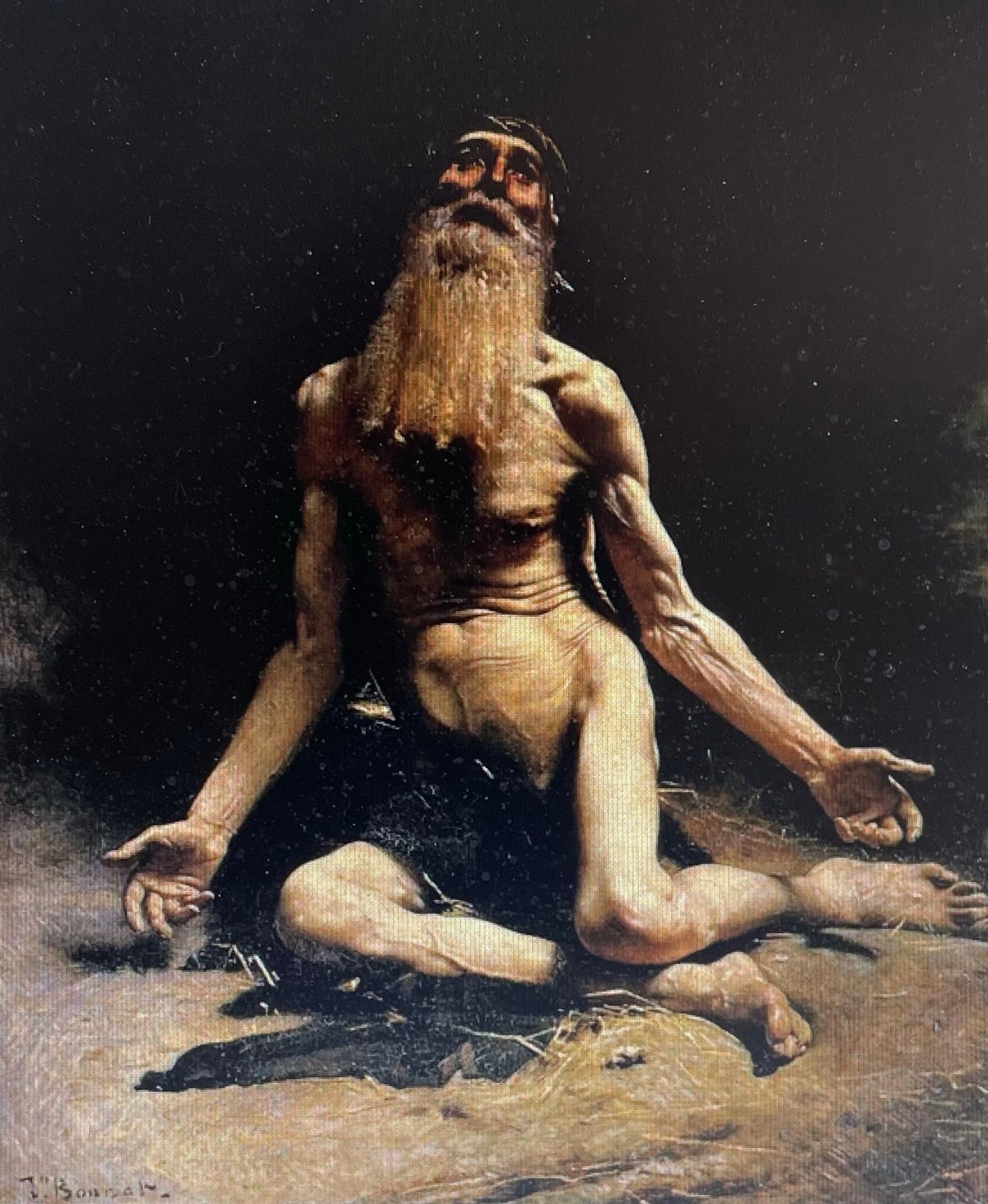

In the first speech of the book, Naomi counts herself as among the dead – her husband and sons are dead and she may as well be dead herself. She now sees her worth measured solely by the ability to produce sons. With some irony on the part of the author, Naomi recommends that her 2 daughters in law find security in a husband’s house, apparently forgetting that the house of a husband to date has provided neither safety or security for any of them.

Ruth counters with a speech that is brief and to the point, and pledges a commitment and loyalty far beyond what is required. Few of us today can really appreciate how great this commitment really is. To abandon one’s ancestral homeland, family and gods in favour of those of a foreigner was an enormous risk, and acceptance by the new community was by no means assured. It meant learning new customs, preparing new foods, a new language and a new folklore. That Ruth is constantly referred to as a ‘Moabite’ suggests that she (and the narrator) are aware that her ethnicity is an immense barrier to her full inclusion in the new community.

When we read this story, we forget that racism and nationalism were as rampant in ancient times as they are now. We may unconsciously view Judaism as the ‘right’ religion, and thus a natural and desirable course of action for Ruth. The truth is that inter-ethnic relationships were complex and often viewed very unfavourably by the ruling elite of Israel, as the books of Ezra and Nehemiah make very clear. For example, in chapter 9 of Ezra, the officials refer to the “abomination” of inter marriage with Moabites and other races, and state that this “pollutes” the holy seed of Israel. Integration was not easy; acceptance not guaranteed.

Naomi does not seem convinced by Ruth’s speech, but allows her to continue with her whilst the more obedient Orpah returns to her homeland. For Naomi to be burdened with even one Moabite woman in her homeland of Israel may have lowered her status as a poor widow further and stretched her already meagre means. In other words, where we are easily impressed with Ruth’s speech of devotion, it is questionable if Naomi was. The narrator merely states that seeing “how determined” Ruth was, Naomi “stopped speaking to her”. The rest of the journey is not mentioned, and no further conversation recorded.

Naomi’s final lament that she wants to be known as “Mara”, meaning bitterness, rather than Naomi, meaning sweetness, suggests that she is not yet grateful for Ruth’s exceptional gesture of solidarity and loyalty with her. She laments that she returns empty, her daughter in law’s devotion is ignored.

It is also worthy of note that while Naomi is recognised by the women of Bethlehem, Ruth has been rendered invisible. Neither the townsfolk nor Naomi refer to her presence. The narrator alone makes reference to her, reminding us that not only is she Ruth the Moabite, but also Naomi’s daughter in law.

Ruth 2

The first chapter of Ruth was intended to challenge the reader’s or hearer’s stereotypes about women, loyalties, and national origin by the use of humour and irony. The relationship of Naomi and Ruth is meant confront hearers about what they thought they knew and invites them to ask new questions that help them begin to rethink their view of “the world as it should be.”

By this strategy and others that keep the hearer/reader guessing throughout the chapter, the book of Ruth has begun by turning expectations upside down and subverting the dominant world vision.

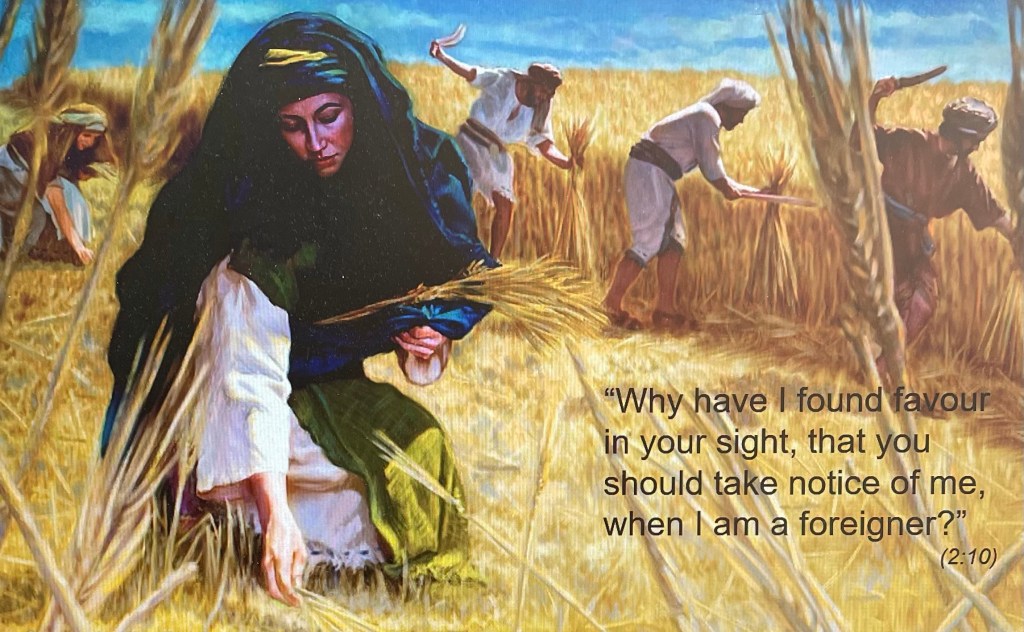

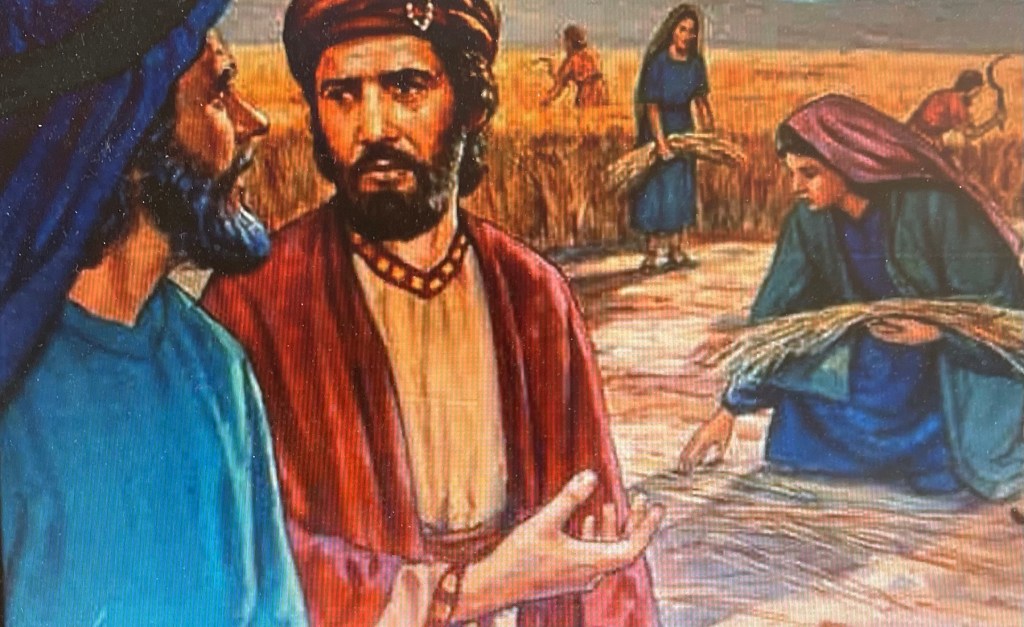

Chapter 2 picks up the story of Ruth and Naomi as they settle into life at Bethlehem. Though the famine which drove Naomi and her family from Israel has ended, action is required so that food might be put on the table. Ruth therefore proposes that she go and glean in the fields. As a poor foreign widow, this is Ruth’s only means of survival, as gleaning was the main means of support for the poor in Israelite law. Up to this point, the story has been about two widowed women supporting each other.

Ruth’s industrious activities draw the attention of Boaz, the owner of the field in which she gleans. Despite being poor, female and a Moabite, Ruth finds favour in the eyes of Boaz, rich, male and Jewish. By strange coincidence, Boaz is the kinsman of Naomi. A good translation of his Hebrew name is ‘pillar of the community’.

On Boaz’ appearance, the Hebrew reader is likely to be asking some serious questions. Why isn’t he helping Naomi as Israelite familial duty would dictatehe should – especially seeing he is so upright in the community and so obviously rich? Why has she been left to fend for herself, facing deprivation and possible starvation? Why does Boaz only take an interest in Naomi’s fate after he sightedRuth?

The chapter has a lot of complex interplays going on, between foreigner and Israelite, male and female; old and young; rich and poor; powerful and powerless. The author subverts most of the prevailing stereotypes as the story progresses.

Ruth stated at the beginning of the chapter to Naomi that she hoped to ‘find favour’in someone’s eyes. “Finding favour” in the Hebrew Bible generally means that a woman is desirable in the eyes of men. Coupled with the pervasive Israelite belief that Moabite women were sexually immoral (Gen 19 and Numbers 25 allude to this), the author is stressing both Ruth’s vulnerability – and her desirability.

We turn now to Boaz. His first question is “To whom does this young woman belong?”, a most irrelevant question as far as his interests as a landowner are concerned. The author is communicating Boaz’s very keen interest in Ruth.

The foreman identifies Ruth as the young Moabite woman who returned with Naomi. There is a conversation between Ruth, and Boaz. She has fallen prostrate at his feet. Such deference is usually reserved for God. Ruth twice uses the phrase “found favour in your sight”, the phrase that indicates a love interest. Boaz evokes the name of the Lord. Apart from her speech in chapter one, Ruth shows no interest in the Lord, the God of Israel. Instead she makes it clear her fate is going to lie with Boaz, not the God of Israel.

This is emphasised by her saying that Boaz has ‘spoken to her heart’ (mistranslated as ‘spoken kindly’ by the NRSV), another phrase frequently used in the Hebrew bible to indicate a love interest. Ruth is signalling her availability and interest in Boaz, but she has also shown she will not be bullied into an inequitable relationship.

Back at home, Naomi undergoes quite a transformation in relation to Ruth when she sees the amount of grain Ruth has gleaned. Naomi is no fool either, andknows by the cooked food Ruth has given her, and by the huge amount of barley, that something unusual is afoot and that there is a man involved. Hence her first questions “Where did you glean today?” Where did you work?” are quickly followed by “Blessed be the man who took notice of you”. One does not come across large portions of cooked food or ephahs of grain in the normal course of gleaning.

Naomi’s response is to initially call down a blessing on Boaz, in a reference to herself and her late husband. Again, the discerning Hebrew reader must be wondering here why Boaz has failed to act for Naomi before this time. For the first time Naomi reveals the familial connection to Boaz, and calls him goel, or redeemer. This term indicates a close family member with an assigned role in family legal matters, usually financial. To date Boaz has proved a rather unreliable goel, and Naomi is quick to capitalise on his apparent interest in Ruth by warning her against gleaning in another field “lest she be bothered”.

Despite being poor, female and a Moabite, Ruth has reversed the normal social order to find favour in the eyes of Boaz, rich, male and Israelite. The harvest scenes evoke themes of life and fertility that point towards blessings to come. But for the moment, life is still difficult, and the women’s future needs to be secured.

Despite Ruth’s resourcefulness, she and Naomi are still in a category of people whose well-being depends on the actions of others. The shortcomings of Israelite society that the book highlights challenge us to look more closely at our own cultural context, and how the poor and the foreigner are welcomed and provided for in our community.

Even in a world where prosperity has become available for some on a ridiculous scale, many still die of starvation. Many flee countries where food supplies are insufficient, and where opression is rife. It is clear that true community in our world is broken. While gleaning may be unknown to us, it has been replaced by our welfare system, which is often inadequate to address the real issues facing the poor.

If nothing else, the story of Ruth here should challenge us to work for cultural change, to a society where all are equally valued.

The author of Ruth is a political commentator of the times. He or she disagrees with the extreme nationalistic sentiments of Ezra and Nehemiah, and wants to offer another point of view, a point of view where personal qualities of faith, love and loyalty are placed ahead of race and country of origin. So be with us next week, as we see how this unfolds in the remaining two chapters.