“We have a great high priest who has passed through the heavens, Jesus, the Son of God, so let us hold fast to our confession; for we do not have a high priest who is unable to sympathize with our weaknesses, but we have one who in every respect has been tested as we are, yet without sin” (Heb 4:14–15).

In this way, the anonymous author of the word of encouragement written to the Hebrews highlights what will be come the overriding image, the dominating theme, of the whole book. (On the nature of this book, see https://johntsquires.com/2021/09/29/the-word-of-exhortation-that-exults-jesus-as-superior-hebrews-1-pentecost-19b/)

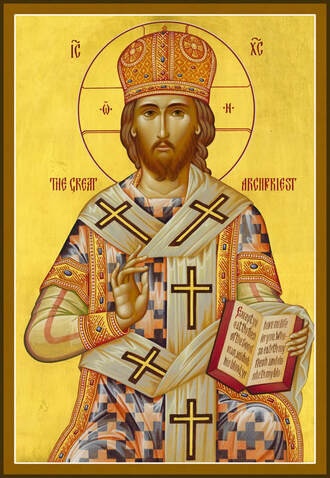

The author has already identified Jesus as “a merciful and faithful high priest in the service of God, to make a sacrifice of atonement for the sins of the people” (2:17), the “apostle and high priest of our confession” (3:1). The claim that Jesus was a sinless high priest (4:15) is striking. He is being placed at a level above and beyond the already high level of the Jewish high priest. This is the foundation for the argument that is proposed and developed in subsequent chapters

When Jesus is designated high priest according to “the order of Melchizedek” (5:10; 6:20), he is understood to be the high priest who has “passed through the heavens” (4:14) and is “holy, blameless, undefiled, separated from sinners, and exalted above the heavens” (7:26). We will come back to the mysterious Melchizedek next week.

As Jesus is seated at God’s right hand (8:1), he is able to enter into the holy place of “the greater and perfect tent” (9:11–12) to offer the sacrifice which “makes perfect those who approach” (10:1, 14). The comparison is made using the long-existing system of offerings and sacrifices which were integral to the Israelite practice of religion.

The Temple was the central point of faith for the people; it was the focus of pilgrimage at festival times, the place where priests mediated between the people and God through the offerings and sacrifices, the place where the rich liturgical life of ancient Israel was developed (as we see in the psalms).

The comparison that is made is stark: the earlier Jewish system of offering sacrifices is exposed as flawed, insufficient, and now rendered redundant. We will return to this element of the comparison in a later post, when we consider again the picture of Jesus as priest in this word of exhortation (the letter to the Hebrews).

The purpose of using the imagery of sacrifice and priesthood in this book is not intentionally negative towards the Jewish sacrificial system. The constructive purpose of this language is to demonstrate that Jesus brings the process of sanctification to a head (13:12; see also 2:11; 9:13–14; 10:10, 14, 29) and enables believers to “approach [God] with a true heart in full assurance of faith” (10:19–22).

This work is not unique in drawing on the language of the sacrificial cult. The death of Jesus is interpreted in language drawn from the sacrificial practices of Israel. He is the one “who gave himself for our sins to set us free from the present evil age” (Gal 1:4), who “loved us and gave himself up for us, a fragrant offering and sacrifice to God” (Eph 5:2), who “gave himself for us that he might redeem us from all iniquity and purify for himself a people of his own who are zealous for good deeds” (Titus 2:14).

Paul draws on the sacrificial system of the Temple when he encourages the followers of Jesus “to present your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to God, which is your spiritual worship” (Rom 12:1-2). He points to his own life as an example, saying that “I am being poured out as a libation over the sacrifice and the offering of your faith” (Phil 2:17), and then encouraging the Philippians that, “in the same way, you also must be glad and rejoice with me” (Phil 2:18).

In another letter attributed to him, but more likely written at a later time by one of his followers, invoking his name to claim his authority, this line of instruction recurs. The saints addressed in the letter allegedly written to the Ephesians directs that they are to “live in love, as Christ loved us”, following the author’s example of living as “a fragrant offering and sacrifice to God” (Eph 5:2).

The Gospel writers use language drawn from the sacrificial cult describe Jesus; most obviously, in the description of Jesus as “the lamb of God” (John 1:29, 36)—there was an unblemished lamb offered daily at the Temple in sacrifice (Exod 29:38–46). The saying that the Son of Man came “to give his life a ransom for many” (Mark 10:45) uses the language of the cult (Exod 21:30); that language is used to describe the effect of the death of Jesus in later letters (Eph 1:17; 1 Tim 2:6; 1 Pet 1:18–19).

The language of covenant, used in the accounts of the last meal that Jesus shared with his followers (Mark 14:24; Matt 26:28; Luke 22:20; 1 Cor 11:25) itself draws from the foundational understanding of the people of Israel. This covenant was the very heart of their relationship with God that undergirded the sacrificial system of the people of Israel (Exod 24:1–8; Lev 26, see verses 9, 15, 25, 40–45). At its heart, the remembrance of the body broken and the blood shed at the final meal of Jesus—the central enduring ritual within the Christian church—continues to evoke the sacrificial practices of ancient Israel.

The way that the idea is developed in Hebrews, however, is curious. Paradoxically, Jesus both stands in the place of the priest slaughtering the sacrificial beast (2:17; 3:1; 5:1–6; 6:20; 7:26–28; 8:3; 10:12) and simultaneously lies on the altar as the one whose blood is being shed (9:11–14; 9:26; 10:19; 12:24; 13:20). Although the details of the imagery are confused, there is a consistently firm assertion developed through this image: Jesus is the assurance of salvation (2:10; 5:9; 10:22).

The use of this idea throughout the book is a piece of contextual theology. It makes use of ideas and practices well-known in the world of the time, to explain the significance of Jesus and to interpret the meaning of his death.

Portraying Jesus as priest is intended to provide comfort to the readers. As the great High Priest, Jesus is now able to broker the relationship between believers and God, in the way that the High Priest did for centuries. That Jesus is the high priest who has “passed through the heavens” (Heb 4:14) provides strong assurance.

Portraying him as victim, however, seeks to make sense of the brutal death of Jesus, suffocating to death of the cross, his dead body laid in a tomb. This death was not in vain; it is effective in securing God’s forgiveness and grace, just as the victims sacrificed in the temple cult removed the sins and provided forgiveness to those who brought those sacrifices. The sacrifice of Jesus “makes perfect those who approach” (Heb 10:1). And because the one who is sacrificed is the same one as the perfect priest making the sacrifice, “by a single offering he has perfected for all time those who are sanctified” (Heb 10:14).

The logic is strange, to us; to the author of Hebrews, it obviously made perfect sense.

A priest forever, “after the order of Melchizedek” (Hebrews 5; Pentecost 21B)