Each year for the Festival of Pentecost, alongside the story from Acts 2, the lectionary places a section from the latter part of Psalm 104 (Ps 104:24–34, 35b). The whole psalm is a stirring poem on the beauty and grandeur of God’s creation, worth reading in full for the grand sweep over earth and seas and sky that it offers.

The section proposed for Pentecost has been chosen, it seems clear, for the two references to the spirit that are included. The first links the spirit with God’s creative work: “you send forth your spirit, they [God’s creatures] are created; and you renew the face of the ground” (v.30).

The second reference (v.29) is less obvious in many English translations. The same word, ruach, is used in this verse as in the following verse. In v.29, God is said to “take away their breath [ruach], [so] they die and return to their dust”. In v.30, at the other end of life, God is said to “send forth your spirit [ruach], [so] they are created”. God’s spirit is given at birth and taken away at death. The same word, ruach, indicates the same divine spirit which imbues all human beings. Rendering it differently in these two consecutive verses is mischievous!

The section of the psalm offered for Pentecost affirms that the many works of God (quaintly translated as “manifold” in the NRSV and the NIV, following the earlier KJV) are created “in wisdom” (v.24). What has come before this verse, as well as what immediately follows it, is all encompassed within this overarching claim that these many works are the fruit of divine wisdom.

The psalm has already identified, as part of God’s creativity, the heavens (vv.2–4) and the earth, with its mountains (vv.5–9); it continues with descriptions of rivers, streams, and rain (vv.10–13; and see more at vv.25–26), noting the various classes of creatures—wild animals (v.11), birds of the air (v.12), cattle and plants (v.14), as well as sea creatures (vv.25–26), leading on to the production of food to nourish humanity—wine, oil, and bread (v.15; and see more at vv.27–28).

The threefold classification of creatures evident in this psalm is found elsewhere in Hebrew Scriptures. In Psalm 8, another psalm which offers praise to God (“how majestic is your name in all the earth”, vv.1,8), those who are placed “under the feet” of human beings are “all sheep and oxen, and also the beasts of the field, the birds of the air, and the fish of the sea, whatever passes along the paths of the seas” (Ps 8:7–8).

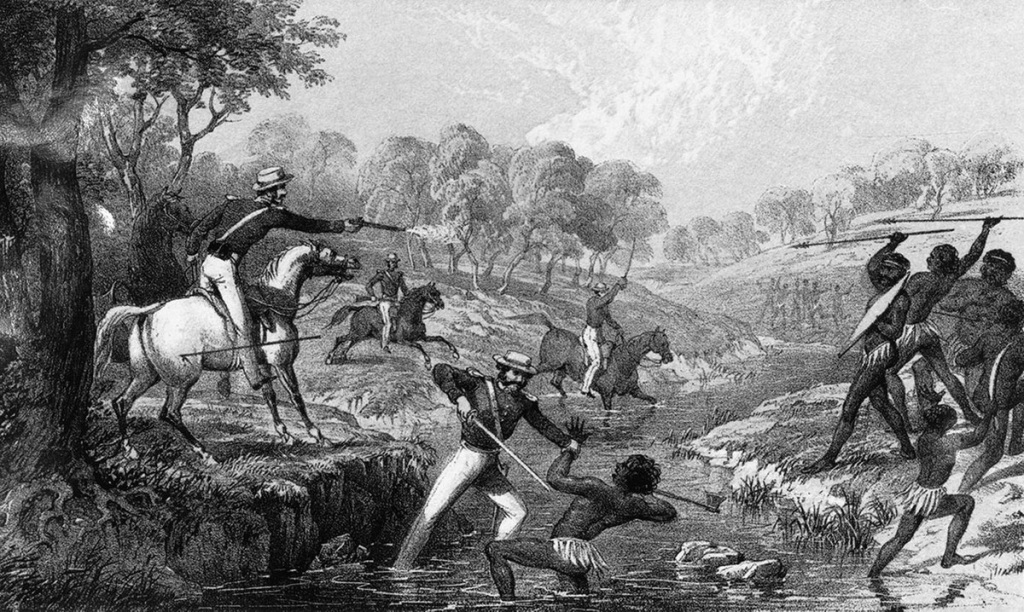

This echoes the declaration of God found in the priestly account of creation, after humanity is made “in the image of God”, that humans will have “dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the birds of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the wild animals of the earth, and over every creeping thing that creeps upon the earth” (Gen 1:26, 28). It also resonates with the commitment of God to Noah and his sons, after the great flood, that “the fear and dread of you shall rest on every animal of the earth, and on every bird of the air, on everything that creeps on the ground, and on all the fish of the sea; into your hand they are delivered” (Gen 9:2). The same classification is noted in the prohibitions of idols that Moses delivers to the people of Israel (Deut 4:15–18) and an early speech of Job in response to Zophar (Job 12:7–8).

After the food produced to nourish humanity (v.15), there follows mention of trees, birds, and wild animals (vv.16–18) including lions (vv.21–22); interpersed between these are the sun and the moon (vv.19–20), and concluding with the daily labour of human beings (v.23). All of these are wrapped into the inclusive statement, “O Lord, how many are your works! In wisdom you have made them all; the earth is full of your creatures” (v.24).

All of these elements—heaven and earth, sea and land and sky, birds and animals both domesticated and wild—are included in this listing of God’s creation, made in wisdom, all created by the breath of God (v.30) and all returning to dust when their breath is taken from them (v.29). The psalm draws to a close with a typical stanza of praise (vv.31–34), in which the psalmist sings with joy: “I will sing praise to my God while I have being; may my meditation be pleasing to him” (vv.33b—34a).

It is worth noting that the lectionary—typically—omits the main part of the final verse, in which the psalmist prays, “let sinners be consumed from the earth, and let the wicked be no more” (v.35a). This is a typical petition which is found in a number of psalms (Ps 1:5–6; 9:5, 17; 11:6; 21:9; 28:3–5; 34:21; 37:9, 20; 58:3–10; 59:13; 68:2; 71:13; 75:8–10; 90:7; 101:7–8; 119:119; 129:4; 139:19; 145:20; 146:9; 147:6), so it should not surprise us; the judgement of God was always seen to exist alongside the steadfast love of the Lord in the songs of the psalmists.

Including this verse in the excerpt that we read and hear on Pentecost Sunday both maintains the integrity of the text, and invites the preacher to address the full picture of the deity that is found in the texts of Hebrew Scriptures.

![I am the good shepherd [who] lays down his life for the sheep (John 10; Easter 4B)](https://johntsquires.files.wordpress.com/2024/04/img_4491-1.jpg?w=1200)