Today is ANZAC Day. It is an annual commemoration that has been held since 1916, which was the first anniversary of the landing of Australian and New Zealand troops on the Gallipoli Peninsula during the early stages of World War I. These troops were the first of approximately 70,000 Allied soldiers whose service included time at Gallipoli; more than 20,000 of these troops were Australian and New Zealand soldiers.

The website of the Australian War Memorial states: “The Australian and New Zealand forces landed on Gallipoli on 25 April, meeting fierce resistance from the Ottoman Turkish defenders. What had been planned as a bold stroke to knock Turkey out of the war quickly became a stalemate, and the campaign dragged on for eight months.

“At the end of 1915 the allied forces were evacuated from the peninsula, with both sides having suffered heavy casualties and endured great hardships. More than 8,000 Australian soldiers had died in the campaign. Gallipoli had a profound impact on Australians at home, and 25 April soon became the day on which Australians remembered the sacrifice of those who died in the war.” See

https://www.awm.gov.au/commemoration/anzac-day/traditions

The first ANZAC Day was observed in 1916 in Australia, New Zealand and England and by troops in Egypt. That year, 25 April was officially named ‘Anzac Day’ by the Acting Australian Prime Minister, George Pearce. It has been held every year since then on the same date, 25 April. It has become, in Australia, a day that commemorates the roles played by Australian servicemen and servicewomen in many arenas of conflict beyond World War I.

So we rightly pause, today, to remember all that is involved warfare: the contributions of these service people, but also the many victims of war, those who lost their lives, those who lost their health and livelihood, those who lost their loved ones, those who lost all hope.

War has many consequences. It damages individuals, communities, societies, and nations. It has many more innocent victims than the casualty lists of enrolled personnel indicate. And there is abundant evidence that one war might resolve one issue, but often will cause other complications which will lead to another war. Look at the outcome of the Armistice at the end of World War One: we can trace a direct sequence of events that led from World War One to World War Two.

In recent years, in ANZAC Day ceremonies, there has at last been due recognition given to Indigenous men who enlisted in our armed services. The War Memorial has an educational programme on this topic for schoolchildren; see

https://www.awm.gov.au/visit/schools/programs/indigenous-service

For many years, the Australian War Memorial insisted that its concern is solely with “Australians serving overseas in peacekeeping operations or in war”. A decade ago, a previous Director, Dr Brendan Nelson, infamously asserted that “the Australian War Memorial is concerned with the story of Australians deployed in war overseas on behalf of Australia, not with a war within Australia between colonial militia, British forces, and Indigenous Australians.” See

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/sep/12/australian-war-memorial-ignores-frontier-war

This means that the War Memorial does not include any memory of the thousands of indigenous people who were killed on Australian soil over many decades, in The Frontier Wars (nor, indeed, those white colonials who also died in these encounters). You can read more about this at https://www.awm.gov.au/blog/2013/12/17/response-question-about-frontier-conflicts/

More recently, in 2023, the recently-appointed chair of the War Memorial, Kim Beazley, says he supports “proper recognition of the frontier conflict” as part of the institution’s $500m expansion, questioning how the institution can “have a history of Australian wars without that”. See https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/australian-war-memorial

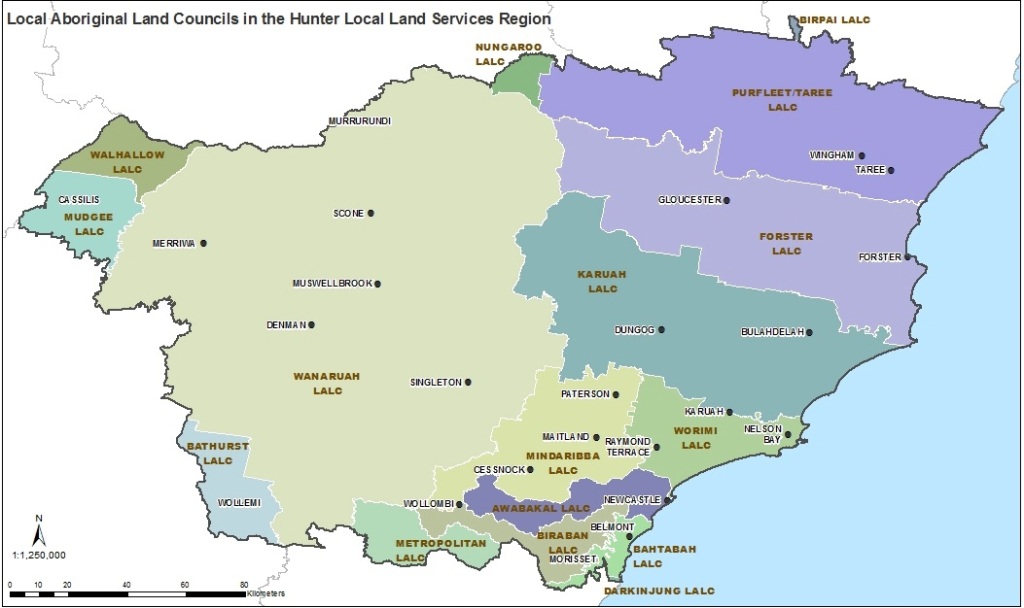

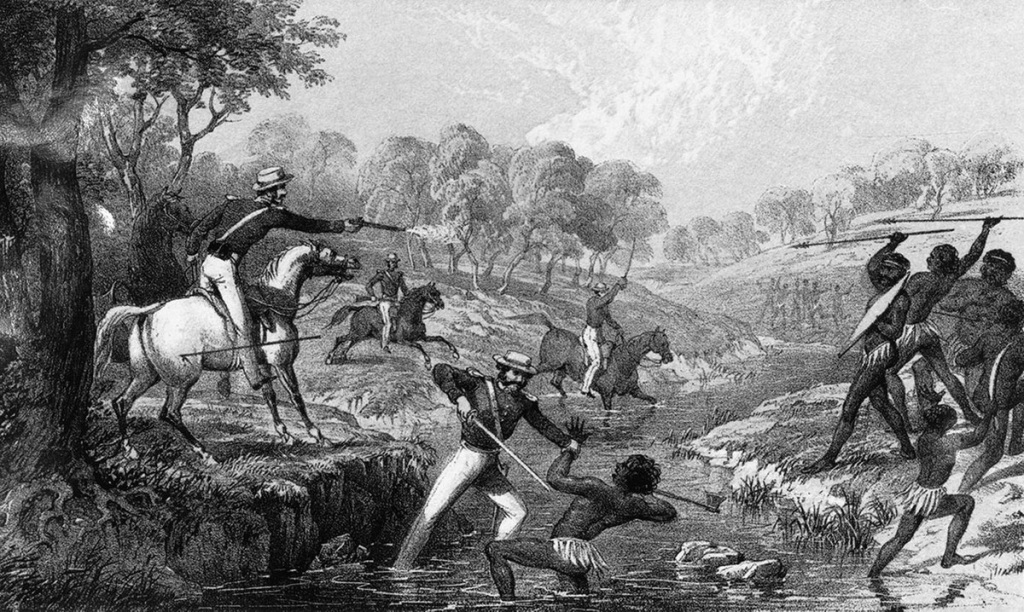

Studies have indicated that, over those decades, more indigenous people died here, in Australia, at the hands of the colonisers, than the 60,000+ Australians who died in 1915—1919 on foreign soil, fighting a European war at the behest of our imperial overlords.

[Raymond Evans and Robert Ørsted-Jensen used statistical modelling to hypothesize that total fatalities suffered during Queensland’s frontier wars were no less than 66,680. See http://treatyrepublic.net/content/researcher-calls-recognition-frontier-wars]

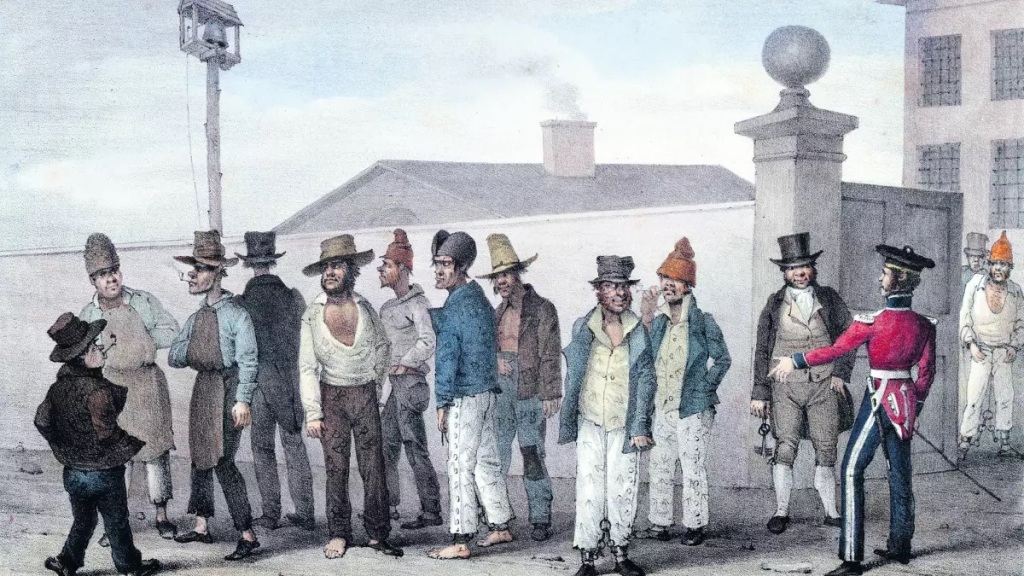

The Australian War Memorial blog cited above states, “The ‘Frontier Wars’ were a series of actions that were carried out by British colonial forces stationed in Australia, by the police, and by local settlers. It is important to note that the state police forces used Indigenous Australians to hunt down and kill other Indigenous Australians; but the Memorial has found no substantial evidence that home-grown military units, whether state colonial forces or post-Federation Australian military units, ever fought against the Indigenous population of this country.”

The myth that there was no official, state-sponsored military force which was charged with the task of dealing with “the troublesome natives” (or however else they were described in derogatory terms), is, however, punctured by this Wikipedia note: that on 3 October 1831, Governor Stirling appointed Edward Barrett Lennard as Commanding Officer of the Yeomanry of the Middle Swan, a citizens militia to pursue and capture Aboriginal offenders, with Henry Bull appointed as Commander of the Upper Swan.

The orders were that on being called out, the Yeomanry were “to cause the offending tribe to be instantly pursued, and if practicable captured and brought in at all hazard, and take such further decisive steps for bringing them to Punishment as the Circumstances of the Case may admit.” [Wikipedia here quotes from Michael J. Bourke (1987). On the Swan: a History of the Swan District of Western Australia. Nedlands, WA: University of Western Australia Press.]

The evidence is clear: Australian servicemen have been party to an officially-organised programme to attack First Nations people. And the evidence is also clear, that across the continent over many decades, thousands upon thousands of Indigenous people have been massacred by the invading British settlers and troopers. See the careful historical work of Prof. Lyndall Ryan and her team in the Centre for 21st Century Humanities in the Newcastle University, at

https://c21ch.newcastle.edu.au/colonialmassacres/map.php

So today, as we remember those who served in war and the many victims of war, let us remember also the victims of The Frontier Wars, indigenous and white alike … especially the many thousands of First Nations people who died in these wars.

See more at