“Comfort, comfort all my people”, sings the prophetic voice which opens the second major section of the book of Isaiah (chapters 40—55). Widely considered to be written in a period later than the time when the earlier sections are located, this section of Isaiah is called Deutero—Isaiah, signalling that it is the second main section of the book. (The third main section, chapters 56—66, is called Trito—Isaiah.)

The comfort sung about by the prophet signifies the situation of the people: their forebears had been taken into exile by the Babylonians in 587 BCE, and now a new generation (perhaps four to five decades later) yearns to return to the land of Israel, given to the people in ancient times, as recounted in the foundational myth—story of the Exodus. Other parts of the Hebrew Bible reflect the anguish of the people during their time of Exile (Ps 137 is the most famous instance). Deutero-Isaiah, however, focuses consistently on the hope of return to the land of Israel.

Looking to the new power of Persia to permit this return, the prophet of this later period speaks with hope and joy, to the people living in exile, using vivid imagery and dramatic scenes of promise and confidence. A joyous, positive tone runs right through the oracles in this section of Isaiah. “I am about to do a new thing”, says the Lord; “I will make a way in the wilderness and rivers in the desert” (43:19). “I will pour water on the thirsty land and streams on the dry ground”, the Lord continues; “I will pour my spirit upon your descendants, and my blessing on your offspring” (44:3).

The return to Israel is depicted in vivid scenes: “I will make of you a threshing sledge, sharp, new, and having teeth; you shall thresh the mountains and crush them, and you shall make the hills like chaff” (41:15). It is especially envisaged as a re-enacting of the Exodus through the Red Sea; “I will make a way in the wilderness and rivers in the desert, for I give water in the wilderness, rivers in the desert” (43:19–20); “when you pass through the waters, I will be with you; and through the rivers, they shall not overwhelm you” (43:2).

The imagery reaches back to the start of Genesis; “the Lord will comfort Zion; he will comfort all her waste places, and will make her wilderness like Eden, her desert like the garden of the Lord” (51:3). Indeed, the Lord as creator is emphasised a number of times (40:28; 43:7, 15; 44:2, 24; 45:12, 18; 48:1).

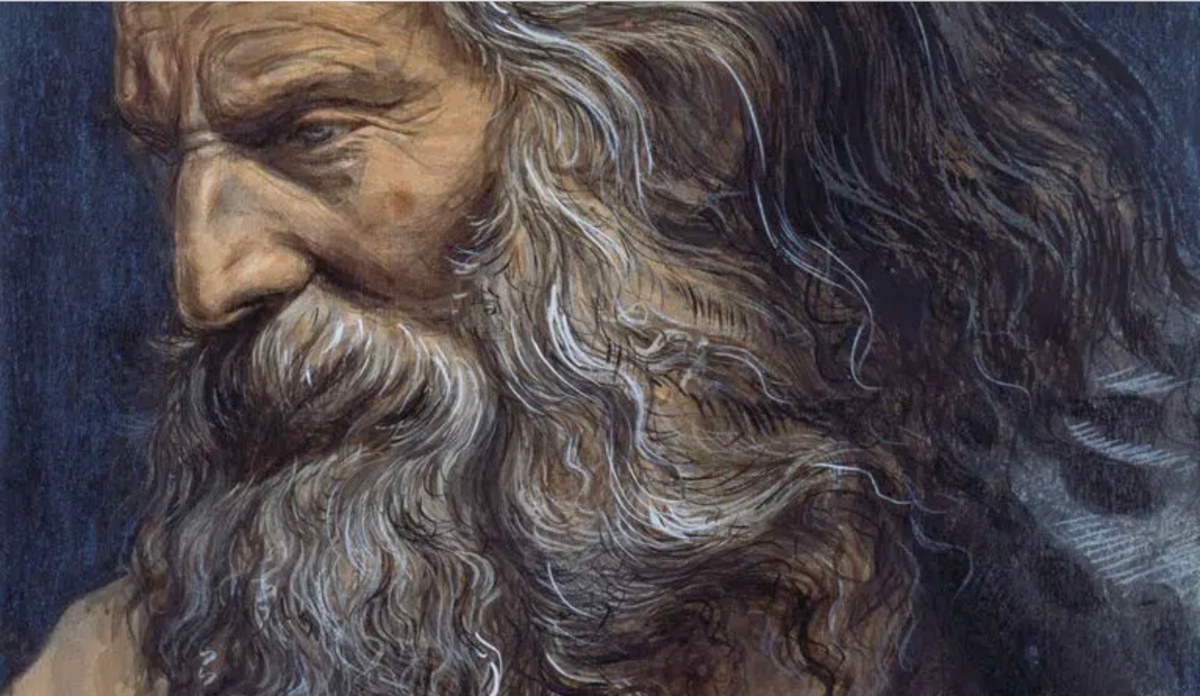

Key to this promised return to the land of Israel is Cyrus, the Persian ruler, who lived from about 600 to 530 BCE. Cyrus led the Persians to dominance in the region from around 550 BCE onwards. The Persian Empire stretched around the eastern edge of the Mediterranean Sea, from the Hellespont (the Dardanelles) in the west to the Indus River in the east.

A defining feature of Cyrus is that he respected the religious practices and cultural customs of the lands he conquered. The evidence for this,policy comes from an artefact known as the Cyrus Cylinder, made of clay (and now broken into a number of pieces). The Cylinder was found in modernity in 1879 during an expedition under the auspices of the British Museum, near a large shrine to the chief Babylonian god Marduk.

The Cylinder articulates the policy which undergirded the decision of Cyrus to allow the exiles in Babylon to return to the land of Judah (2 Chron 36:22–23; Ezra 1:1–10). The Cylinder does not refer directly to Judah or Israel, but it does include the line, “the gods, who resided in them [a list of cities across the Tigris], I brought back to their places, and caused them to dwell in a residence for all time, and the gods of Sumer and Akkad … I caused them to take up their dwelling in residences that gladdened the heart”.

Because of this policy, Cyrus is most strikingly described by Deutero-Isaiah as the Lord’s anointed one (45:1), the one of whom the Lord says, “he is my shepherd and he shall carry out all my purpose” (45:28). The prophet affirms that the Lord says, “I have aroused Cyrus in righteousness, and I will make all his paths straight; he shall build my city and set my exiles free, not for price or reward” (45:13). (The Hebrew word used, mashiach, is the same used to refer to the one anointed as Messiah at Dan 9:25–26; it is translated into Greek as Christos, from which Jesus is known as the Christ.)

Choosing a foreigner, the ruler of the dominant empire of the time, to carry out the will of the God of Israel, is a bold claim indeed. It is a striking development in Israel’s theology, especially since an intensified nationalism—indeed, xenophobia—is evidenced in literature from the time when people have returned (Ezra and Nehemiah, in particular).

After the return to the land under Cyrus (2 Chron 36:22–23), the narrative books which follow immediately, Ezra and Nehemiah, recount the details of this return as the walls around the city of Jerusalem are rebuilt (Neh 2—6, 12), the Temple is rebuilt and rededicated (Ez 3, 5–6), the Law is read in the city and the covenant with the Lord is renewed (Neh 8—10).

*****

Because of this word of good news about the fate of the exiles, God is regularly described as Redeemer (Isa 41:14; 43:14; 44:6, 24; 47:4; 48:1, 17; 49:7, 26; 54:5, 8). God is also regularly named as “the Holy One” (Isa 40:25; 41:14, 16, 20; 43:3, 14, 15; 45:11; 47:4; 49:17; 49:7; 54:5; 55:5), picking up a title found already in other texts (1 Sam 2:2; 2 Ki 19:22; Job 6:10; Ps 71:22; 78:41; 89:18; Prov 9:10; Isa 1:4; 5:19, 24; 10:17, 20; Ezek 39:7; Hos 11:9, 12; Hab 1:12; 3:3).

Later, Jesus is described in ways that use both terms: as “the one to redeem Israel” (Luke 24:21; see also Rom 3:24; 1 Cor 1:30; Gal 4:5; Eph 1:7, 14; Col 1:14; Tit 2:14; Heb 9:11–12), and as the “Holy One” (Acts 3:14; 1 John 2:20).

Within these oracles of promise and hope, the theological understanding of monotheism is clearly articulated for the first time in the history of Israel. “Is there any god besides me? There is no other rock; I know not one” (44:8). The phrase, “there is no other (god)”, recurs a number of times in this section (42:8; 45:5, 14, 21, 22; 46:9).

This is in contrast to the way that the God of Israel had previously been portrayed, as “among the gods” (Exod 15:11; Judg 2:12; Ps 86:8), with the commandment to have “no other gods before me” (Exod 20:3; Deut 5:7) distinguishing this God from those other gods whom Israel was clearly forbidden to worship (Deut 6:14; 7:4; 8:19; 11:16; 13:1–18; 17:2–5; 18:20).

Time after time, the straying of Israel to worship these ”other gods” resulted in punishment sent by the Lord (Josh 23:16; Judg 2:11–23; 10:13; 1 Sam 8:8; 1 Ki 9:6–9; 11:9–13; 14:6–14; 2 Ki 17:7–8, 35–40; 22:14–17; 2 Chron 7:19–22; 28:25; 34:24–25; Jer 1:16; 7:16–20; 11:9–13; 16:10–13; 19:4–9; 22:6–9; 32:29; 35:15–17; 44:1–19; Hos 3:1—4:11). Monotheism was not in view in earlier, pre-exilic literature.

As a consequence of this development, if the Lord God is the only god, then the Lord must take responsibility for all that takes place: “I form light and create darkness, I make weal and create woe; I the Lord do all these things” (45:7). This affirmation creates problems; if God causes both good and bad things to happen, he is accountable for all that takes place.

Over time, this theological development would lead to the development of another theological milestone: the creation of an opposing force who would be held responsible for all evil. The accuser from the heavenly court, delegated by God to prosecute cases (Job 1:6–12; 2:2–8; 1 Chron 21:1; Zech 3:1–10) would become Satan, tester of Jesus (Mark 1:13), fallen heavenly being (Luke 10:18), and “deceiver of the whole world” (Rev 12:9; 20:2–3).

*****

Deutero-Isaiah is fundamental, in other ways, for the theological developments that we find in the New Testament. Scattered through this section, we find four Songs of the Servant—three relatively brief (42:1–9; 49:1–7; 50:4–11); and the fourth, best-known within Christian circles, a longer description of the servant who “was despised and rejected by others; a man of suffering and acquainted with infirmity” (Isa 52:13–53:12).

The resonances that this longer song has with the passion narrative of Jesus are crystal clear. The song is explicitly linked with Jesus six times in the New Testament (Matt 8:14–17; Luke 22:35–38; John 12:37–41; Acts 8:26–35; Romans 10:11–21; 1 Pet 2:19–25); furthermore, so many of the details of the passion narrative are shaped in the light of this song, along with a number of psalms of the righteous sufferer. (See https://johntsquires.com/2021/03/22/3-mark-placing-suffering-and-death-at-the-heart-of-the-gospel/)

The list of connections with details in the passion narrative is impressive. The prophet describes the marred appearance of the Servant (52:14); he is despised, rejected, and suffering (53:3), bearing our infirmities (53:4), and wounded for our transgressions (53:5). The Servant is led like a lamb to the slaughter (53:7), suffering “a perversion of justice” (53:8), not practising violence or speaking deceit (53:9), and is buried with the rich (53:9).

The Servant gives his life as “an offering for sin” (53:10), carrying the iniquities of many (53:11), making them righteous (53:11), bearing the sin of many (53:12), making “intercession for the transgressors” (53:12). The role that the Servant plays in relation to sin, for the sake of the many, shapes the important saying of Jesus, that “the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life a ransom for many” (Mark 10:45).

Deutero-Isaiah as a whole is the most-quoted part of Hebrew Scripture in New Testament texts. Another element in the Servant songs shapes the way that Luke envisages the story of Jesus and his followers. The Servant is given “as a covenant to the people, a light to the nations” (Isa 42:6), as “a light to the nations, that my salvation may reach to the end of the earth” (Isa 49:6).

The phrase is cited at critical moments by Simeon (Luke 2:32), Paul and Barnabas in Antioch (Acts 13:46–47), and Paul alone when on trial in Caesarea (Acts 26:23). Jesus foresees that witness to the good news will take place “in Jerusalem, in all Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth” (Acts 1:8).

Further, the Servant is given as “a light to the nations, to open the eyes that are blind, to bring out the prisoners from the dungeon, from the prison those who sit in darkness” (Isa 42:6–7), words which resonate with the later scriptural citation spoken by Jesus in Nazareth: “the Spirit … has sent me to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free” (Luke 4:18).

The author of the fourth Gospel also made much of what was spoken to the Servant, “you are my servant, Israel, in whom I will be glorified” (Isa 49:6), a description of what happens to Jesus which recurs regularly in this book, when “the Son of Man has been glorified” (John 13:31; see also 7:39; 11:4; 12:16, 23, 28; 13:32; 17:10).

The prophet reports the decision of the Lord: “I have taken from your hand the cup of staggering; you shall drink no more from the bowl of my wrath, and I will put it into the hand of your tormentors” (51:22). Accordingly, any oracles of judgement and threat of punishment are directed squarely towards Babylon, (43:14; 45:20-47:15), not Israel (54:9).

The closing oracles of this section of Isaiah promise abundance and peace to the exiles, looking towards their return to the land. “Enlarge the site of your tent, and let the curtains of your habitations be stretched out … you will spread out to the right and to the left, and your descendants will possess the nations and will settle the desolate towns” (Isa 54:2–3). Israel is invited to “come, buy wine and milk without money and without price” (55:1), with the assurance that “as the rain and the snow come down from heaven, and do not return there until they have watered the earth, making it bring forth and sprout, giving seed to the sower and bread to the eater, so shall my word be that goes out from my mouth; it shall not return to me empty” (55:10–11).

Deutero-Isaiah ends with a portrayal of cosmic joy as the exiles prepare to return to Israel: “the mountains and the hills before you shall burst into song, and all the trees of the field shall clap their hands” (55:12). All will be well.

*****

See also