The church’s year (currently, Year A) draws to a close this coming Sunday, with the festival of the Reign of Christ. After this Sunday, we enter a new church year, as the season of Advent begins (for Year B). The church’s year is organised differently from the calendar year; it revolves around the key events of our faith: the birth of Jesus, which we celebrate each Christmas, the death and resurrection of Jesus, which comes into focus at Easter, the birth of the Church, which we recall at the celebration of Pentecost, and the long season after Pentecost, when we attend to our life as disciples and the mission into which we are called as people of faith.

What I am referring to as the festival of the Reign of Christ has been known traditionally as the festival of Christ the King, when we commemorate the reign that Christ exercises over the world. I prefer the term Reign of Christ as at least one step away from the connotations that are associated with that archaic institution of monarchy. And that flags one of the issues that I have with this feast day—more below.

This is a relatively new festival in the calendar of church festivals—it was introduced by Pope Pius XI in 1925, and has since been adopted by Lutheran, Anglican, and various Protestant churches around the world, and also, apparently, by the Western Rite parishes of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia. (Yes, that is a real denomination!) So that is a second issue that I have with this day—along with Trinity Sunday, it sits as a day devoted to “a doctrine” developed later in the church’s life, rather than “a time in the life of Jesus”, which is what Christmas and Easter is, or “a time in the life of the church”, namely, Pentecost.

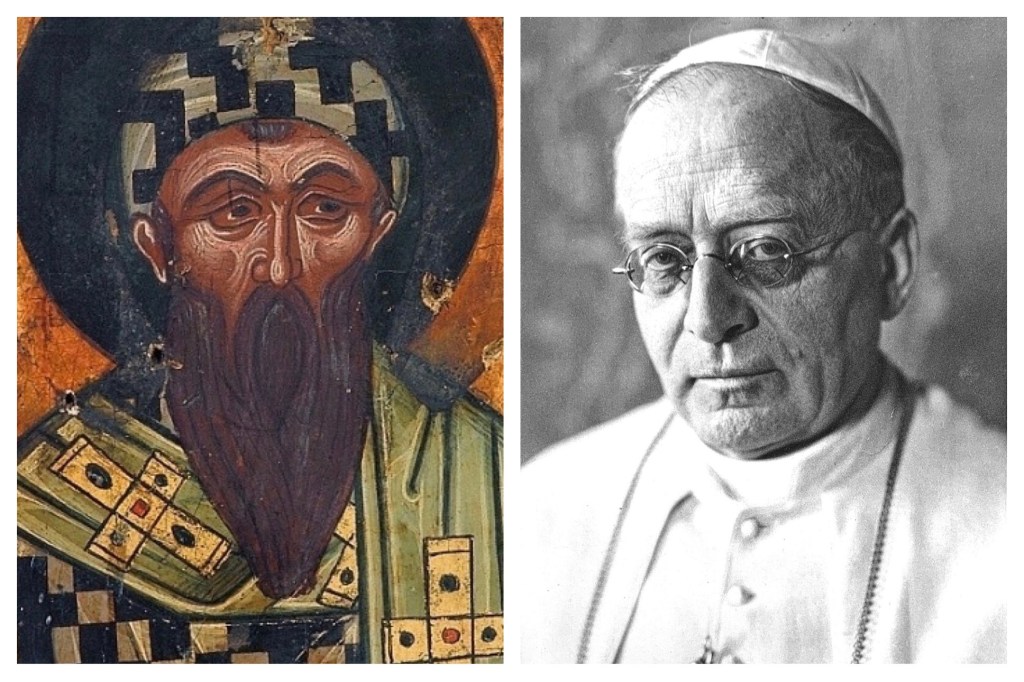

In Roman Catholic tradition, the day is explained by some words from Cyril of Alexandria, a fifth century Doctor of the Church who served as Patriarch of Alexandria, in Egypt, from 412 to 444. In establishing this festival, Pope Pius XI quoted from the writings of Cyril: “Christ has dominion over all creatures … by essence and by nature … the Word of God, as consubstantial with the Father, has all things in common with him, and therefore has necessarily supreme and absolute dominion over all things created. From this it follows that to Christ angels and men [sic] are subject. Christ is also King by acquired, as well as by natural right, for he is our Redeemer. …’ We are no longer our own property, for Christ has purchased us with a great price; our very bodies are the members of Christ.”

(born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti)

Now, if you wonder where the Pope derived this understanding from, then perhaps the words offered this Sunday by the Revised Common Lectionary, from the letter to the Ephesians, might have provided the foundations for this grand cosmic vision of the place of Jesus, the Risen Lord, in the overall scheme of things (Eph 1:15–23). This section of the letter is a prayer of thanks, as the writer affirms that “I do not cease to give thanks for you as I remember you in my prayers” (1:16), and indicates that “I pray that the God of our Lord Jesus Christ, the Father of glory, may give you a spirit of wisdom and revelation as you come to know him” (1:17).

A part of that wisdom and revelation is the image of the resurrected Jesus, who is seen as seated at the right hand of God “in the heavenly places, far above all rule and authority and power and dominion, and above every name that is named” (1:20–21). That place of authority for Jesus is envisaged as stretching into eternity, “not only in this age but also in the age to come” (1:20), and as encompassing all places, for God “has put all things under his feet and has made him the head over all things” (1:22). The global and eternal rule of Christ is here clearly articulated.

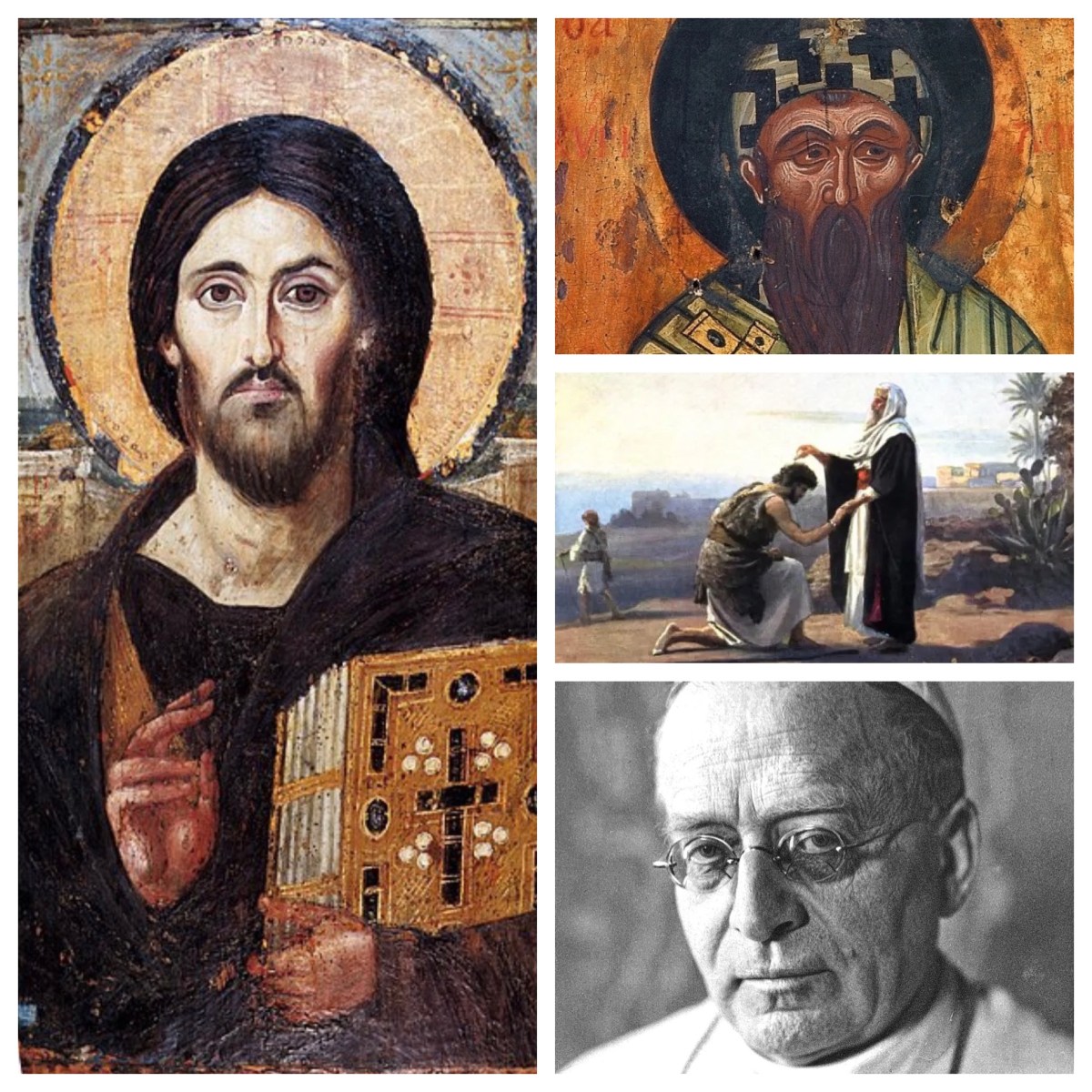

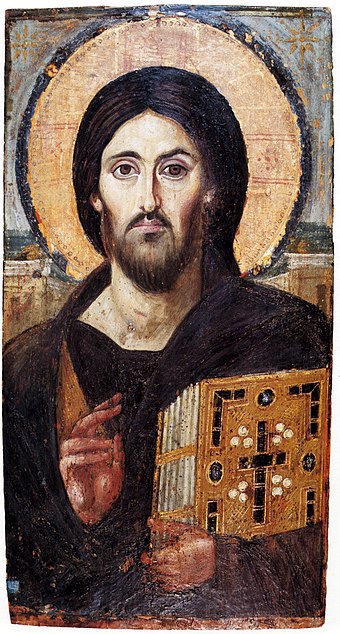

The statement by the writer that God “seated [Jesus] at his right hand in the heavenly places, far above all rule and authority and power and dominion” (1:20–21) has inspired the development of the imagery of Christ as Pantocrator (Greek for “ruler of all”) in Eastern churches, both Orthodox and Catholic.

In icons from the sixth or seventh century onwards, Christ Pntocrator appears in a standardised manner, which depicts him “fully frontal with a somewhat melancholy and stern aspect, with the right hand raised in blessing or, in the early encaustic panel at Saint Catherine’s Monastery, the conventional rhetorical gesture that represents teaching. The left hand holds a closed book with a richly decorated cover featuring the Cross, representing the Gospels.” See

https://www.cappadociahistory.com/post/pantocrator-the-most-important-icon

One of the images associated with the king in ancient Israel was the shepherd. The prophet states this most clearly when he declares God’s words: “my servant David shall be king over them; and they shall all have one shepherd” (Ezek 37:24). This connection underlies the Hebrew Scripture passage for the Sunday of the Reign of Christ, which comes from this prophet.

Ezekiel had been exiled to Babylon during the siege of Jerusalem by King Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon (599 BCE; see 2 Kings 24:10–17). His prophetic activity was undertaken entirely in exile. He addresses both those in exile with him in Babylon, and also those left behind in Judah. His prophecies continue through the period when the people in Judah were conquered and taken to join Ezekiel in exile (587 BCE; see 2 Ki 25:1–21), and then for some time after that.

As the destruction of Jerusalem occurs in that year (33:21–29), Ezekiel berates “the shepherds of Israel”: “you have not strengthened the weak, you have not healed the sick, you have not bound up the injured, you have not brought back the strayed, you have not sought the lost, but with force and harshness you have ruled them” (34:4). The disaster for Jerusalem that is taking place, he considers, is due to their poor leadership.

In contrast, God himself will “will search for my sheep, and will seek them out. As shepherds seek out their flocks when they are among their scattered sheep, so I will seek out my sheep. I will rescue them from all the places to which they have been scattered on a day of clouds and thick darkness” (34:11–12). God will find a way to exercise good, healthy leadership within the nation.

So the extended oracle of this chapter ends with the affirmation, “you are my sheep, the sheep of my pasture and I am your God, says the Lord God” (34:31). The mercy of God is bound up with the justice of God, and the king is expected to exemplify that. The resonances that this passages has with Psalm 23, as well as the sayings of Jesus in John 10 and the well-known parable of Jesus found in Luke 15 and Matt 18, are clear.

There follows an extended blessing on Israel (36:1–38) and the well-known vision of bones brought to life in the valley (37:1–28), followed by visions relating to Gog and Magog (38:1–39:20; and see Rev 20:7–8). Finally, as the exile ends, and Ezekiel speaks of the restoration of Israel to their land (39:21–29); “I will never again hide my face from them, when I pour out my spirit upon the house of Israel, says the Lord God” (39:29). Good shepherds will rule once again, is the promise—although they will not be accorded the title, or have the power, of a monarch.

There is, however, a king in the Gospel reading proposed for this Sunday. It is the final parable of Jesus included in Matthew’s book of origins (25:31–46), in which the Son of Man appears and exercises the authority of the king that had been envisaged over the centuries in the story of Israel.

In Hebrew Scripture, the king of Israel was expected to “judge [the] people with righteousness, and [the] poor with justice” (Ps 72:1–2). Here, in the parable, the king assesses the actions of those who come before him, inviting the righteous to “inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world” (Matt 25:34) and cursing others to “depart from me into the eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels” (Matt 25:41). This king clearly judges according to the righteousness and justice of God.

We know, of course, from the narratives that tell the story of Israel over many generations (1–2 Samuel, 1–2 Kings, 1–2 Chronicles), that many kings failed in this requirement, and “did evil in the sight of the Lord”, fulfilling the predictive prophecy of the prophet Samuel (1 Sam 8:10–18). Nevertheless, the idealised view of kingship, which Samuel dutifully set out in writing for the people (1 Sam 10:25), held sway through the ensuing centuries.

This idealised vision of kingship was particularly developed in the scriptural portrayal of Solomon, who is portrayed as being filled with “wisdom and knowledge” and granted “riches, possessions, and honour, such as none of the kings had who were before you, and none after you shall have the like” (2 Chron 1:7–12, especially verses 10 and 12).

Does the festival of the Reign of Christ draw on the idealised view of kingship that Hebrew Scripture advocates? Is Jesus put forward as the King who fulfils the hopes for Israelite kingship—which so many of the kings of the past had failed to achieve? That’s a disturbing, possibly antisemitic, way of treating the stories of scripture.

Or even more disturbingly, does the festival of the Reign of Christ reflect the height of Christendom, ideas first shaped by Cyril in the 5th century, then adopted and expanded by Christian rulers over the centuries (Charlemagne, or Vladimir the Great, for example)? That, too, is worrying.

The reality is that this festival was introduced into the liturgical cycle of the Roman Catholic Church by Pope Pius XI in 1925, at a time when Fascist dictators were rising to power in Europe. I have read that “the specific impetus for the Pope establishing this universal feast of the Church was the martyrdom of a Catholic priest, Blessed Miguel Pro, during the Mexican revolution”; see Today’s Catholic, 18 Nov 2014, at

The article continues, “The institution of this feast was, therefore, almost an act of defiance from the Church against all those who at that time were seeking to absolutize their own political ideologies, insisting boldly that no earthly power, no particular political system or military dictatorship is ever absolute. Rather, only God is eternal and only the Kingdom of God is an absolute value, which never fails.”

The scriptures puncture the pomposity of powerful kings, and subversively present Jesus as the one who stands against all that those kings did. This festive day shares in that purpose. In that sense, and only in that sense, this is a feast day to maintain and support.

See also