Late last year, Elizabeth and I moved to Dungog, a rural town with a population of a little over 2,000, nestled amidst the rolling hills beside the Williams River, one of the tributaries that flows into the Hunter River. (The other major tributaries include Moonan Brook, Stewarts Brook, Pages Creek, Pages River, Paterson River, Goulburn River, and Wollombi Brook.)

The town has one picture theatre, one high school, two primary schools, three pubs, five active churches, five sports clubs, and six tennis courts. It is the place where Test cricketer Douglas Walters was born (in 1945) and later married, and where indigenous boxer Dave Sands died, aged 26, in a road accident in 1952.

The traditional lands of the Gringai include an area centred on the place where the town of Dungog is situated, next to the Williams River. It is often said that the name Dungog is derived from a word meaning “clear hills” or “thinly wooded hills” in Gathung, the language spoken by the Gringai .

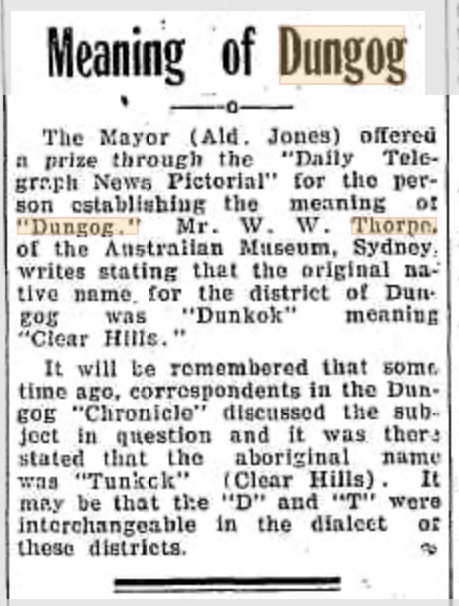

However, this is disputed by historians of the area, who maintain that this was most likely an incorrect explanation introduced in the 1920s. In an attempt to generate a growth in tourism to the town, the then Mayor of Dungog was looking for a perhaps slightly more ‘poetic’ meaning for the name of his town. The Mayor offered a prize through the “Daily Telegraph News Pictorial” for the person establishing the meaning of “Dungog”.

The Dungog Chronicle of 24 May 1927 (see above) reported that “Mr W.W. Thorpe of the Australian Museum, Sydney” declared that the original native name for the district of Dungog was “Dunkok” meaning “Clear Hills”.

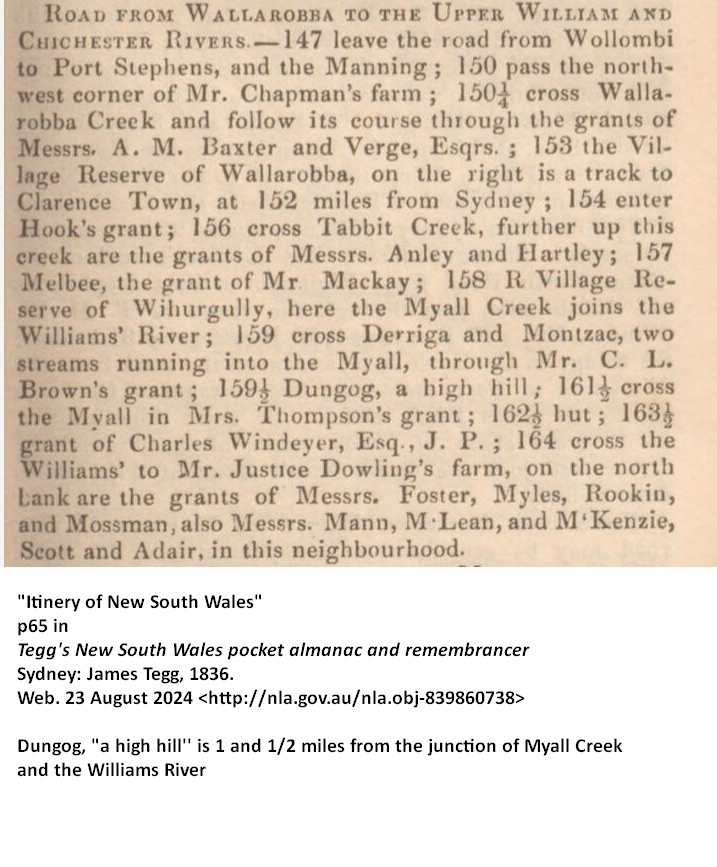

There are, however, references from the 1830s which offers a different explanation. On page 145 of The New South Wales calendar and general post office directory, 1832, there is a detailed description of the route of travel north from Sydney along the road to Wallarobba to what was then known as Upper William, the original name for the British village of Dungog.

In this directory we are told that at a mile past the Melbee Estate comes the point where “the Myall Creek joins the William’s River”, at which is a “village reserve” called, not Dungog, but Wihurghully. The road then continues “following the course of the Myall, along its western bank” for another mile and a half, when it comes to “Dungog, a high hill, part of the range, dividing the waters of the William and Myall”. So the word was originally the name of a specific location, a high hill, to the east of where the town now sits.

As I have done with each move of recent times, I have taken some time to investigate a little of what is known about the First Peoples of the area to which we have moved. I have been exploring the stories about contact between the invading British colonisers and the First Peoples who have cared for the land from time immemorial.

In years past, I have found stories about people in the places where Elizabeth and I have lived: the Eora peoples of Sydney, where I grew up and lived for decades; the Biripi peoples, on the mid north coast of NSW; and the Noongyar peoples, of Perth, WA. More recently, I have read and learnt about the Ngunnawal, Ngarigo, and Ngambri peoples, whose lands overlapped in the southern of Canberra, where we were living. It is always an enriching process. You can find the link to my blogs about these peoples and their lands at the end of this blog.

This time, the task of investigating and reporting has been somewhat more difficult. The land council for the area where the Gringai lived is based in Karuah, where the Karuah River flows into Port Stephens. As far as I can tell, there are very few people who claim Gringai heritage today in the area. The invading British colonisers, in their insatiable search for land to settle in the early 19th century, were quite thorough, it would seem, in removing from that land those Indigenous people who had lived on it for millennia.

There are scattered references to the Gringai people in the writings of the settlers from the late 19th century. (I am indebted to Noel Downs, who provided me with links to this material.) And it seems that there has been some debate about the precise scope of the lands of the Gringai, and their relationship to the neighbouring nations of the Wonnarua and the Biripi.

A local history site refers to “two major tribal groups of the broader Hunter River Valley and coastal region; the Wonnarua of the Hunter Valley and the Worimi of the Port Stephens coast area” and claims that “the Gringai were not a separate tribe but a sub-group of one of the two region’s tribes, though which one is in some doubt, with perhaps the Wonnarua being the more likely.” See

Working from “land borders” is a very western way of operating; we want to identify and demarcate the lands of one people from another by drawing a clear, precise border. We erect fences around houses, draw lines to mark off states and set up different time zones according to those lines, and have stern staff at the borders of the country to ensure that “undesireables” don’t enter the country. It’s all very precise.

However, Indigenous life was not so squared-off and precise. I remember an Aunty in Wauchope telling us about land not far from where we lived, that was in Biripi country but was considered Dunghutti land, as that was where the two groups of people would meet and yarn and trade—and also where marriages were arranged. This is something that jars to western ears—how can both sets of people “own” the same land?

A better way to go is to be guided by the markers which linguists make from their study of what we know of the languages of the peoples of the First Nations. Linguist Amanda Lissarrague has researched and published A grammar and dictionary of Gathang, in which she explores the links between “the languages of the Birrbay, Guringay and Warrimay peoples”.

These languages, spoken on the northern side of the Hunter River, she identifies as the Lower North Coast (LNC) language also known as Katang, or Guthang. This is distinguished from the Darkinjung and Wanaruah, on the south of the Hunter River, who speak the Lake Macquarie (HRLM) language.

[Lissarrague’s argument for linking the three groups into the LNC language is technical: “The evidence for linking Wonnarua (M, F), Awabakal (T), Kuringgai (L) and ‘Cammeray’ (M2) is found when one compares verbal inflections and pronoun forms, including bound pronouns, from different sources.” ]

In 1788, Britain established a penal colony at a place that was named Sydney Cove, after Thomas Townshend, the 1st Viscount Sydney. Early in the colonial era, the invading settlers began moving into the region north of Sydney, building on land and claiming the use of that land, citing the grant of land from the British Governor in support of that activity. That inevitably brought them into conflict with the local pIndigenous peoples, who had cared for this land from time immemorial. We now know that this relationship with the land has stretched back at least 60,000 years—perhaps even longer.

The first exploration of the Hunter, Williams and Paterson Rivers by those invading British colonisers had already commenced just 13 years after that initial settlement in Sydney. Convict timber cutters were sent into the area from 1804 onwards, and small land grants at Paterson were made from 1812, and at Clarence Town from 1825.

By 1825 most of the prime alluvial land along the lower reaches of the Paterson River had been granted to the settlers amongst the British colonists who prosecuted the increasing invasion of Aboriginal land. This scale of settlement drastically reduced the hunting areas of the Indigenous people, restricted their supply of game and materials, and further exposed them to diseases brought by the British, against which they had little or no immunity.

In 1825, Robert Dawson named the Barrington area after the British Lord Barrington (who had never travelled downunder, of course, to this area). Two young Welshmen, George Townshend (1798–1872) and Charles Boydell (1808–1869), arrived in Australia on 22 March 1826 to take up land grants in the region. They named the Allyn River, the locality of Gresford, and their homesteads, Trevallyn and Camyr Allyn, after places near their homes in Wales.

In 1827, surveyor Thomas Florance named the Chichester River after the city of that name in England. Then, in 1829, George Boyle White explored the sources of the Allyn and Williams rivers. (The origins of the name for the Williams River is uncertain; see the excellent discussion at https://williamsvalleyhistory.org/williams-river-origin/)

Land grants along the Williams River were made to a number of men, including Duncan Mackay, John Verge, and James Dowling (after whom the main street of Dungog is named). Dowling was later to become the second Chief Justice of NSW, serving from 29 August 1837 to 27 September 1844, the day of his death.

The practice of obliterating the Indigenous names by imposing English names is evident in a number of names in the region. The river known as Coqun, meaning “fresh water”, was renamed the Hunter River, after Vice-Admiral John Hunter, the second Governor of NSW (1795–1800). The river known as Yimmang is now known as the Paterson River, named after Colonel William Paterson, who surveyed the area beside the river in 1801. Erringi, meaning “black duck”, was renamed Clarence Town in 1832, after the Duke of Clarence, who had been crowned King William IV in 1830—who, of course, never came to the colonies!

Some Gringai words are retained in the names of the Wangat River and the rural locations of Wallarobba (“rainy gully”), Dingadee (“place for playing games”), Wirragulla (“place of little sticks”), Mindarabbah (“hunter”), and Bolwarra (“high place”).

See https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/134093649

See also

https://www.patersonhistory.org.au/museumaboriginal.pdf