Continuing my explorations of the First Peoples of the area which has been cared for by the Gringai people for millennia. The traditional lands of the Gringai include an area centred on the place where the town of Dungog is situated, next to the Williams River. It is thought that the name Dungog is derived from a word meaning “clear hills” in the Gringai language.

It seems that in Gringai land (as elsewhere), contact with whites led to a decline in the numbers of Indigenous peoples in the area within a relatively short time. It is estimated that around 500 Gringai people would have lived in the area in the late 18th century. However, interactions with the invading settlers soon reduced this number. Syphilis contracted from convicts, and other introduced diseases, contributed to this decline in numbers. By 1847, thirty Gringai children had died of measles.

In 1845, Dr McKinlay, a Dungog-based doctor, had reported that the ‘District of Dungog’ (which he described as ‘from Clarence Town to Underbank’), had 63 Aboriginal inhabitants, made up of 46 ‘men and boys’, 14 women, and three children.

the first white medical practitioner in Dungog

There is a short article about Dr McKinlay at https://www.dungogchronicle.com.au/story/7378123/history-dungogs-first-doctor/

McKinlay also estimated that this was only half the number of Aboriginal people living there ten years earlier, which he attributed to “diseases which affected the women and children in particular”. Although typical of its time, this explanation offered an easy way for the invading settlers to excuse their dominating colonising activities, which included poisoning and shooting “the natives”.

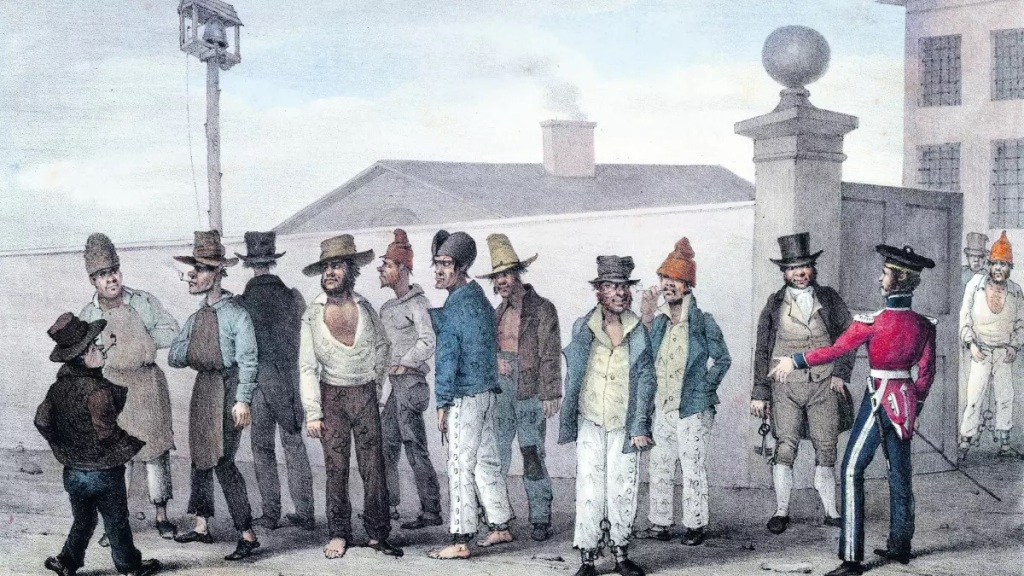

The well-to-do British settlers had high status within the developing society of the Colony. Many deployed their assigned convicts to the work of clearing land and building houses around the district. By the early 1830s the centre of the district was a small settlement first known as Upper William. A Court of Petty Sessions was established in 1833; in 1836, John M’Gibbons was appointed to be the Watch-house Keeper, and Thomas Brown, holding a Ticket-of-Leave, to be Constable at Dungog.

There is a most informative website, History in the Williams Valley, which provides further details. It notes that “Tenders were called in 1837 for the erection of a Mounted Police Barracks and the Police Magistrate was transferred from Port Stephens to Dungog. The first courthouse and lockup was on land now occupied by Dungog Public School and St Andrews Presbyterian Church. The barracks were placed on another hill dominating the town which, after the withdrawal of the troopers, was converted into a new courthouse that continues to operate today.”

See https://williamsvalleyhistory.org/law-order/

It is courtesy of the records of this local court house that two individuals of the Gringai are known by name, because of their arrests and trials. Wong-ko-bi-kan (Jackey) and Charley were both arrested within a year or so of each other in the 1830s.

On 3 April 1834, Jackey (Wong-ko-bi-Kan) was judged guilty and sentenced to be transported to Van Diemen’s Land for manslaughter, after he had speared and killed the settler John Flynn. Flynn had been a member of an armed troop of nine settlers who went to the Gringai camp at the Williams River at dawn to arrest some of them for culling sheep on their land.

From another perspective, of course, Wong-ko-bi-kan could be said to have been defending the native camp from armed intruders. True justice would have been to uphold his rights to his ancestral land—but in this instance, as with thousands of similar cases, the justice that was meted out favoured the recent invading colonisers, not the longterm inhabitants of the land.

It was said that Wong-ko-bi-kan’s case elicited some sympathy from the presiding judge and several observers, because of the way the settlers had approached the native camp with aggression. Wong-ko-bi-kan did not spend much time in Van Diemen’s Land; he died there in prison in October 1834. A sad end to a sorry tale.

(built some decades after the original building)

Another Gringai man, known only as Charley, was arrested in May 1835, soon after the incident with Wong-ko-bi-kan. In August of that year, he was deemed responsible for the death of five convict shepherds who were working for Robert Mackenzie (who would later become Premier of Queensland). Mackenzie had a property at Rawden Vale, 26 miles west of Gloucester.

Charley’s interpreter in the course case was Lancelot Threlkeld, a missionary who had been appointed by the London Missionary Society (LMS) to teach Aboriginal people European agricultural and carpentry skills, and to establish a school for children. The LMS also required Threlkeld to learn the local language, for this was seen to be a precursor which would open the way for successful Christian conversions amongst the Aboriginal people.

Threlkeld reported Charley’s defence, that he had acted after an Englishman had stolen a sacred object, a talisman called a muramai. The man showed the muramai to a native woman with whom he was cohabitating. Charley’s actions were thus in accord with his tribal law, consistent with a decision had been made by the elders.

Charley was sentenced to be hung in public as a warning to other Gringai; this took place in Dungog. Local historian Michael Williams comments that “Charley … was both an enforcer of one law and the victim of the enforcement of another set of laws.” One later story, recounted in 1922 in the Wingham Chronicle, suggests that a raiding party set out to enforce the verdict by hunting other Gringai, managing to round some up and push them all over a cliff at Barrington.

A report in the Sydney Gazette for 27 June 1835 that relates to the Dungog area refers to “the insolence and outrage of Convicts who in the service of gentleman squatters … and out of the reach almost of a magistrate, offend and ill-treat the poor blacks with impunity.” The next year, settler Lawrence Myles, J.P., requested assistance from mounted police because of intelligence he had received “that the Blacks are becoming more troublesome” (from the Dungog Magistrates’ Letterbook of 15 May 1836).

Nevertheless, in 1838 the Police Magistrate, Mr Cook, wrote to the Colonial Secretary that “the conduct of all the Blacks in this neighbourhood has been quiet and praiseworthy during the last two years”. Cook noted this in his Return on Natives taken at blanket distribution for 1838. In this region, as elsewhere in the Colony, the annual report of blankets distributed gives an idea of the numbers of Aboriginal people who were in contact with the British colony.

From the records of blanket distribution, names of some Gringai people are known today: Mereding, known as King Bobby, who had two wives; Dangoon, or Old Bungarry; Tondot, known as Jackey; as well as some men from the Wangat group. The report for 1837 lists 144 “natives”; undoubtedly there were more living in the area not identified in the report. Men named Fulham Derby and Pirrson are identified in a legal process of the same year, for instance, as noted in the Dungog Magistrates’ Letterbook for 14 December 1837.

In the Maitland Mercury for 18 July 1846 (p.2), a visitor to Dungog reported, “On the skirts of the brushwood, we came upon some tribes of blacks, encamped. They are a very fine race here, being chiefly natives of Port Stephens and its neighbourhood. A princely-looking savage, almost hid in glossy curls of dark rich hair, calling himself “Boomerang Jackey,” smiled and bowed most gracefully, saying, “bacco, massa? any bacco?” Some chiefs, with shields, and badges of honour on their breasts, sat silently by the fire with some very young natives, who were going to a “wombat,” or “grand corrobbaree,” when the moon got up.”

Later that same year, the Maitland Mercury (2 Dec 1848, p.2) reported that some farmers in the Paterson area were employing local natives—the price demanded by white labourers was considered too high. “They have certainly exhibited an industry, perseverance, and skill in the execution of their task which cannot be surpassed by Celt or Saxon”, said one farmer. Another noted, “they have done their work very creditably; but unfortunately their habits of industry are not of long duration, and they could not be kept long enough at work to make themselves really valuable.”

The Williams Valley Historical site then notes that “In the last quarter for the 19th century there was an increasing consciousness of severe Aboriginal population decline, the attitude to which was mixed. Many were indifferent; some welcomed it as removing a problem, while a few looked on with pity and made efforts to assist the survivors.”

This site also notes that a number of the settlers exhibited “an interest in tribal habits and customs … of a scientific and anthropological nature … thus James Boydell compiled lists of Aboriginal words, and Dr McKinlay and others made various observations, many of which were used by Howitt. Howitt [also] compiled a study based upon information elicited from many locations, including the Dungog area.” (Howitt, Alfred William, The native tribes of south-east Australia.)

(date and place unknown) under the care

of the Aborigines Protection Board

By the 1880s, across the Colony, a paternalistic approach to dealing with Aboriginal people had gained hold. A “Protector of Aborigines” was appointed, then replaced with the “Aborigines Protection Board”. The Board disapproved of “the system of issuing Government rations to able bodied aboriginals, as it tends to encourage idleness in a large degree”, and maintained that “a supply of flour, suet, and raisins sufficient to make a pudding can be issued to the aged, young and helpless, and those unable to earn a living through bodily infirmity, for Christmas Day”. (Maitland Mercury, 23 July 1887, p.13)

Numbers reported in ensuing years varied, but those noted in various locations were inevitably small. A man named “Brandy” was tagged as “The Last of the Gringai” by writers in the area—but, as is always the case (witness the famous case of Triganini, in Tasmania), this claim ignores the reality of the forced movement and relocation, as we as the continued intermarriage of Gringai with nearby Worimi and Wonnarua peoples. People of Gringai heritage are found today across many parts of The Hunter region, and in Sydney.

After the passing of the Native Title Act in 1993, a group of local Indigenous people worked to make a claim for an area of roughly 9,500 square kilometres (3,700 sq mi). The claim included the towns of Singleton, Muswellbrook, Dungog, Maitland, and the shire council lands of the Upper Hunter.

The claim was made on behalf of the Plains Clans of the Wonnarua People by Scott Franks and Anor, on 19 August 2013. The claim was registered in January 2015 and referred to the Federal Court to deliberate over the claim and to make a determination. However, it was ultimately discontinued and removed from the register of native title claims on 2 March 2020.

The discontinuance appears to have been the result of disputes with other Aboriginal people who claimed native title in the area. These disputes led to an independent anthropologist, Dr Lee Sackett, being appointed by the Court to prepare a report to resolve the different views of native title in the area. Dr Sackett’s conclusions were to the effect that key details of the claim’s structure were not supported by the evidence.

See