Last Sunday, the lectionary took us away from the Gospel of Mark, with an awkward detour into the Gospel of John that will see preachers being invited to grapple for another four weeks with a long, extended discourse of Jesus revolving around the first of seven I AM statements found in this Gospel. The statement that “I am the bread of life” has been motivated by the account of Jesus miraculously feeding a large crowd with only “five barley loaves and two fish”, which is told in the passage heard last Sunday (John 6:1–21).

This coming Sunday, this awkward detour leads us into the opening section of this long discourse, as John 6:24–35 is the passage that the lectionary proposes as the Gospel reading. This passage ends with the first declaration by Jesus, “I am the bread of life” (6:35). After this week, we are in store for further sections of that discourse, dealing with an elaborated exposition of that “bread of life” (6:35–51), the disputes that this teaching generated with the Judaean authorities (6:51–58), and the final section of the discourse where Jesus then has to deal with dissent from his own disciples (6:56–69).

I have often heard preachers grumble about the repetitive nature of these selections—“not another week on ‘the bread of life’”—but I think that this underestimates the intricacy of this chapter, and the complexity of the issues that are signalled as Jesus pursues his teaching about “the bread of life”. So the challenge I am taking up is to offer a series of four blogs in which a number of those issues are explored and explained.

Perhaps the first stumbling block in dealing with this chapter is that it does appear to be incredibly repetitive. The phrase “the bread of life”, for instance, appears four times (6:33, 35, 48, 51), with the stylistic variant “the bread from heaven” another five times (6:31, 32a, 41, 50, 58), the intensified phrase “the true bread from heaven” (6:32b), and “the living bread that came down from heaven” also in 6:51. That does, to be fair, seem like overkill. But other discourses in this distinctive Gospel exhibit a similarly repetitive style (as, indeed, does the first letter attributed to John). It is a particular style which characterises this Gospel—one of the many features that set it apart from the three Synoptic Gospels.

Each discourse in the series of discourses found in the first half of John’s Gospel displays some standard features. Each discourse arises out of a specific incident; in this case, the feeding of the large crowd (6:1–21) is the stimulus for discussing “the bread of life”. The discourse picks up a key word or idea from the report of the incident and develops that idea by relentless repetition. That is an integral part of its style. So there are eleven references to bread in ch.6, just as there had been seven references to water in ch.4, seven references to life or living in ch.5, and later there are twelve references to sheep in ch.10.

In typical Johannine style, the thesis of the discourse is driven by questions and misunderstandings. Questions invite an answer; misunderstandings require an explanation. And so the argument in this whole chapter proceeds by means of a series of questions.

First, after the feeding of the large crowd and the crossing of the lake (vv.22–25), the crowd asks Jesus, “ Rabbi, why did you come here?”(v.25). This opens the way for Jesus to explain that his work is not “for the food that perishes [a reference to the loaves of bread that they had recently eaten], but for the food that endures for eternal life” (v.27). And so the theme for the discourse that follows is set; and the irony that is embedded in the language of “bread” becomes foundational for what follows.

Next, they ask Jesus, “what must we do?” (v.28), allowing Jesus then to define the nature of “the works of God” as “that you believe in him whom he has sent” (v.29)—that is, in Jesus himself. Next, the crowd asks a third question: “what sign are you going to give us? … what work are you performing?” (v.30). They continue by quoting scripture—a move that will prove to be fundamental for the nature of what follows.

By quoting scripture (a variant of Exod 16:4 and 15; also Psalm 78:24) the crowd is gives Jesus his “text” for the teaching that follows. And, of course, as they are Jews, and as Jesus was a Jew, the argument is developed by means of a typical midrashic “playing with the text” in the words that follow. We will come back to the midrashic nature of this discourse in a later blog.

Jesus offers an interpretation of this scripture; it is “not Moses … but my Father in heaven” who provided the bread (v.32). At this point, he pivots from speaking about the bread that God gave from heaven, to speaking about “the true bread from heaven”, himself. He is the bread which “gives life to the world” (v.33).

So this section of the discourse ends, not with a question, but with a request from the crowd; “Sir, give us this bread always” (v.34). Which means that Jesus can now make very clear what his thesis is: “I am the bread of life” (v.35). And so, at last, we get to the point! And at this point, the lectionary passage for this Sunday stops—but we will return next week!

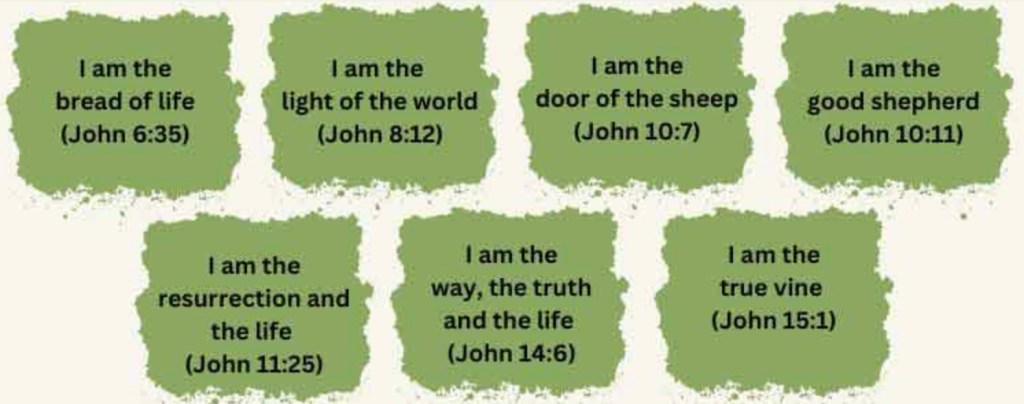

This statement is one of a number of “I Am” statements that are placed on the lips of Jesus in the book of signs, which we know as the Gospel according to John. These sayings comprise a verb (“I am”) followed by a predicate (the entity which Jesus claims to be). The predicates in most of these sayings are drawn from traditional Jewish elements.

When Jesus calls himself “the bread of heaven” (6:25–59), he is clearly evoking the scriptural account of the manna in the wilderness (Ex 16:1–36; Num 11:1–35; Pss 78:23–25; 105:40). The discourse which develops from this saying includes explicit quotations of scripture, as well as midrashic discussions of its meaning.

When Jesus presents himself as “the vine” (John 15:1–11), he draws on a standard scriptural symbol for Israel (Ps 80:8; Hos 10:1; Isa 5:7; Jer 6:9; Ezek 15:1–6; 17:5–10; 19:10–14). Likewise, when Jesus calls himself “the good shepherd” (10:1–18), he evokes the imagery of the good shepherd as the true and faithful leader in Israel (Num 21:16–17; Ezek 34:1–31; Jer 23:4), and the people as the sheep who are cared for (Pss 95, 100; Ezek 34:31).

The statement that Jesus is “the light of the world” (8:12; 9:1–5) evokes the story of the creation of light (Gen 1:3–5) and the light which the divine presence shone over Israel (Exod 13:21–22). The Psalmist uses the imagery of light to indicate obedience to God’s ways (Pss 27:1; 43:3; 56:13; 119:105, 130; etc.), and it is a common prophetic motif as well (Isa 2:5; 42:6; 49:6; Dan 2:20–22; Hos 6:5; Mic 7:8; Zech 14:7; cf. the reversal of the imagery at Jer 13:16; Amos 5:18–20).

Although it is not part of an “I am” statement, the references to the “living waters” which flow from Jesus (4:7–15; 7:37–39) are reminiscent of the water which were expected to flow from the eschatological temple (Ezek 47:1; Joel 3:18; Zech 14:8), and, more directly, refer to the description of God used by the prophet Jeremiah (Jer 2:13).

In addition, biblical scholars have noted that rabbinic symbolism has affinities with Johannine symbols; for example, the terms bread, light, water and wine are all used by the rabbis in connection with the Torah. The author of John’s Gospel stands in the stream of Jewish writers who have used multiple images to convey their faith in the Lord God.

Thus, the distinctive set of Christological claims made for Jesus in the Gospel according to John seek to enter into this stream of writing. They are both thoroughly grounded in scriptural images and familiar from the ongoing traditions taught by the rabbis. The author of this Gospel is using a number of ways to declare his faith in Jesus as “the Word of God”, “the Way”, and indeed as being at one with God. It is a high claim.

Amidst the variety of Jewish voices at the end of Second Temple Judaism clamouring to be holders of “the truth”, using a wide variety of rhetorical means, this author seeks to position his community—a sectarian Jewish group—as the holder of the true faith, the ones who adhere most clearly to what the Lord God requires amongst his faithful people. And for this group, it is Jesus of Nazareth who most clearly and faithfully leads them along that pathway of understanding and living.

See more on this understanding of the community of John at

So this discourse addresses what we might assume to have been a well-known and widespread understanding of the nature of God amongst Jews of the time; he is the one who provides the bread to nourish and sustain lives of faith. When Jesus lays claim to being “the true bread”, it is yet another moment when he says, quite poetically, what he later declares in a very prosaic manner: “the Father and I are one” (10:30).

*****

Still to come in considering the lectionary passages from John 6 that lie ahead:

Jesus offers a midrashic exposition on “the bread of life” (6:35–51): how does Jesus operate in his Jewish context?

Disputing the claim of Jesus to be “the bread of life” (6:51–58): the characters in the story John tells, the sectarian nature of his community

The Johannine remembrance of Eucharistic communion and the community’s distinctive “structure of reality” (6:56–69)

and on the various I AM statements