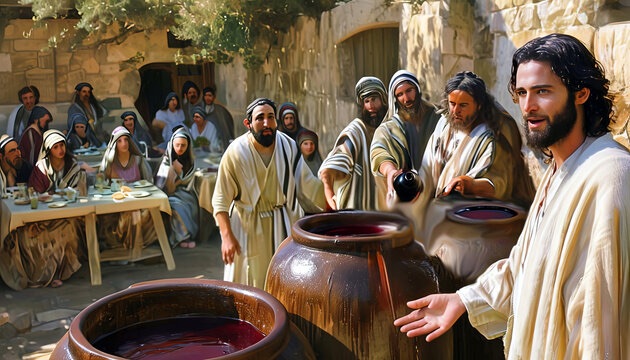

For the second Sunday in Epiphany, we are offered a passage from early in the book of signs—the work that we know as the Gospel according to John. It is the first sign performed by Jesus, when he was attending a wedding in the town of Cana in Galilee (John 2:1–11).

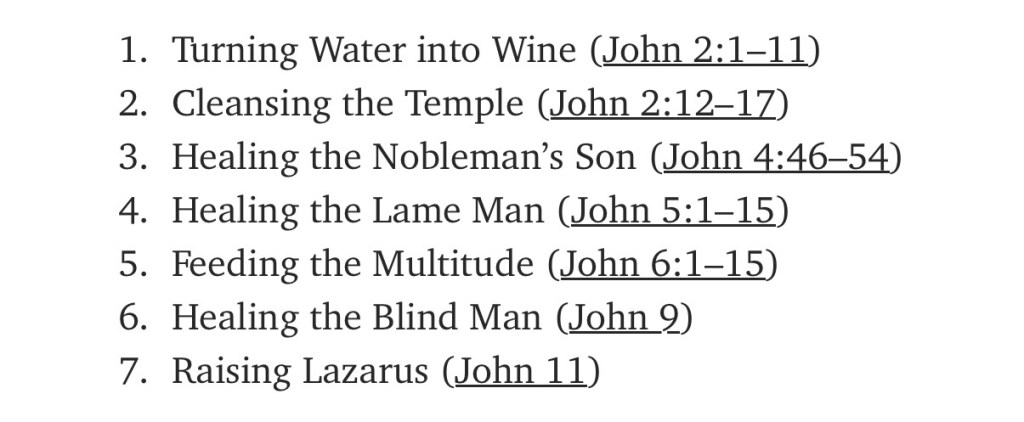

I call this Gospel the book of signs because it includes seven clearly narrated signs, or miracles, performed by Jesus. Most of them are inserted in the midst of an evolving narrative, in which followers of Jesus grow in their understanding of who he is, whilst at the same time a movement of those opposed to Jesus gains strength. Both of those features are evident in this first sign.

The author of this Gospel makes it clear that there were more signs performed by Jesus than what is narrated (20:30), and that the signs actually narrated are told in order to strengthen the faith of those hearing or reading them (20:31).

The first and second signs take place in Galilee (2:1–11, 4:46–54). Subsequent signs are located in Jerusalem (5:2–9), the Sea of Galilee (6:1–14), on the Sea of Galilee near Capernaum (6:16–21), back in Jerusalem (9:1–7) and then, for the seventh, and final, sign of those narrated, in Bethany, where Lazarus had recently died (11:17–44).

This final sign provides a clear climax to the Book of Signs, the first half of the whole Gospel. This is the miracle supreme—raising a dead person back to life takes some beating! It is told at some length, with many details, leading to the climactic moment of the appearance of the once-dead man, now alive. “The dead man came out, his hands and feet bound with strips of cloth, and his face wrapped in a cloth. Jesus said to them, “Unbind him, and let him go.” (11:44).

In the literary framework of the whole Gospel, however, this building to a climax through the seven signs is paralleled by the growing tension as leaders in the Jewish community marshal forces in plotting against Jesus. Initially, there were positive responses to Jesus (2:23, 4:42, 4:45). Then, an engagement in debate and controversy with “the Jews” (5:13) quickly escalated into persecution (5:16) and indeed an attempt to kill Jesus (5:18).

This early opposition then continues unchecked throughout the narrative. Whilst Jesus remained popular in Galilee (6:14, 34) and amongst some in Jerusalem (7:31, 40-41a, 46: 8:30; 9:17, 38; 10:21, 41) and Bethany (11:27, 45), hostility towards Jesus continued, being expressed both in verbal aggression (6:41, 52; 7:15, 20; 8:48; 9:18-19; 10:20), threats of his arrest (7:32, 44; 11:57), direct physical threats (stoning at 8:49, expulsion from the synagogue at 9:22, and stoning once more at 10:31) and threats against his life (7:1, 25, 32).

Then, at the climactic moment, after Lazarus appears, the Jewish leadership plans a strategy to put Jesus to death (11:45-53). The plot is hatched, the fate of Jesus is sealed. That section of the narrative also includes the famous, yet ironic, comment by Caiaphas: “it is better for you to have one man die for the people than to have the whole nation destroyed” (11:50). And so the inevitable process begins, moving towards the death of Jesus (11:53, 57).

For the author of the book of signs, affirming the identity of Jesus shapes the whole narrative of this Gospel. Each sign points to the significance of Jesus. The first sign, in Cana of Galilee, manifests his glory (2:12); the next sign, also in Cana, fosters belief in Jesus (4:48, 53). What Jesus does beside the Sea of Galilee identifies him as “the Prophet who is to come into the world!” (6:14), whilst the sign performed in Jerusalem signal that he is the Son of Man (9:35–38). Later, in Bethany, Jesus raises Lazarus from death, and Martha articulates the faith of others when she confesses Jesus to be Son of God and Messiah (11:27). Alongside these seven signs, the various interpersonal encounters that are narrated illuminate the identity of Jesus.

I read the whole sequence of scenes in this Gospel, from the wedding in Cana, with its implicit criticism of “the Jewish rites of purification” (2:1–11), through the heated debates of chs. 5—8, the high drama of the multi-scene conflict with Jewish leaders and “expulsion from the synagogue” in ch.9, on into the plot of ch.11, as a story that reflects the position of the followers of Jesus who comprised the community in which this book was eventually written.

This group of people (what Raymond Brown called “the community of the beloved disciple”) had been rejected by their fellows, expelled from their community of faith, because of their views about Jesus. They had become yet another sectarian group in the mixture of late Second Temple Judaism, which then bled into early Rabbinic Judaism.

It is this “Johannine sectarianism”, as Wayne Meeks called it, which explains the bruising debates in this Gospel; Jesus is being remembered as “standing up for the truth” by a group of people who had been pillaged and persecuted for standing up for what they say as “the truth”. They had become outsiders; some of them had met death for the stand they took. This was what it meant for them to be faithful to Jesus.

This tragic development is a natural development, at least as the author tells it, from that initial sign, where Jesus is already portrayed as being in tension with others of his own faith. Although it was a wedding—a time of joyous celebration—there were ominous clouds overshadowing what transpired in Cana that day.

Wayne Meeks, “The Man from Heaven in Johannine Sectarianism”, JBL 91 (1972) 44–72)

Raymond E. Brown, The Community of the Beloved Disciple (Paulist, 1978)