A little over five years ago, Elizabeth and I bought land in Dungog. It was a half-acre block in the centre of the town; the block which has the house that we are have been living in, now, for just over 18 months. It turns out that we are just the latest in a line of people who have owned this particular block.

We know the names of the previous owners of this block from the legal documentation that came with the title to the land. And we have been able to find something about each of these owners—from the person who was originally granted the land in 1842, right up to the people who bought the house and land in 1969, from whose deceased estate we bought the house and land a few years back. We have found this through searching the internet and sifting the material we have found.

The block of land in Brown St was part of the original area of land in the town that was made available in 1838 to settlers by the Governor of the Colony of New South Wales, Sir George Gipps. Of course, this land and the surrounding region (like all land that had been granted to the invading British colonisers) had been the land of the Indigenous people of the area for millennia.

As I have done with each move of recent times, I have taken some time to investigate a little of what is known about the First Peoples of the area to which we have moved. I have been exploring the stories about contact between the invading British colonisers and the First Peoples who have cared for the land from time immemorial.

The First Peoples of this area are the Gringai. The traditional lands of the Gringai include an area centred on the place where the town of Dungog is situated, next to the Williams River. It is thought that the name Dungog is derived from a word meaning “clear hills” in the Gringai language. I have explored what we know of the Gringai and this area in my earlier blogs

Once the British government started sending convicts to this continent, and began the process of claiming the land from the Indigenous people, the British system of law, and of land and property, became dominant as new settlements were opened up for the incoming settlers.

(In the following four paragraphs, I am quoting from https://mhnsw.au/guides/land-grants-guide-1788-1856/)

“In 1825 the sale of land by private tender began (Instructions to Governor Brisbane, 17 July 1825, HRA 1.12.107-125). There were still to be grants without purchase but they were not to exceed 2,560 acres or be less than 320 acres unless in the immediate vicinity of a town or village.

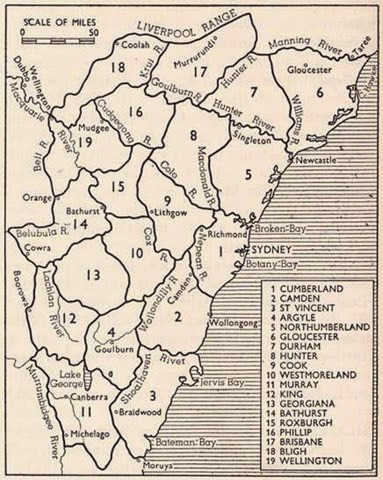

“On 5 September 1826, a Government order allowed Governor Darling to create the limits of location. Settlers were only permitted to take up land within this area. A further Government order of 14 October 1829 extended these boundaries to an area defined as the Nineteen Counties.

“In a despatch dated 9 January 1831, Viscount Goderich instructed that no more free grants (except those already promised) be given. All land was thenceforth to be sold at public auction (HRA 1.16.22) and revenue from the sale of land was to go toward the immigration of labourers.

“Following this, land was sold by public auction without restrictions being placed on the area to be acquired. After 1831 the only land that could be made available for sale was within the Nineteen Counties. This restriction was brought about to reduce the cost of administration and to stem the flow of settlers to the outer areas.”

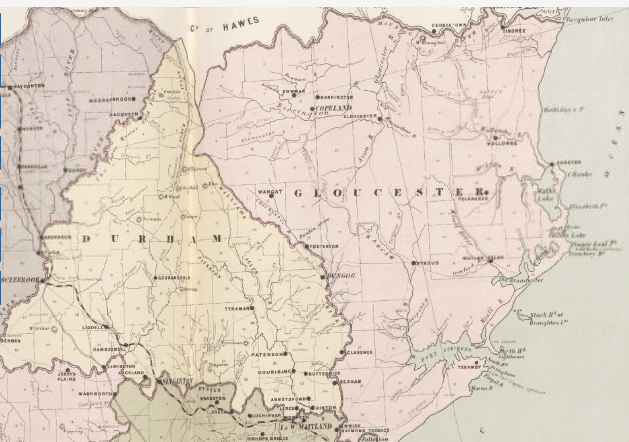

The first county, Cumberland, had been established soon after the British colony was established, in June 1788. a second county, Northumberland, was proclaimed in 1804. By 1820, nine counties had been established: Roxburgh, Northumberland, Durham, Westmoreland, Cumberland, Argyle, Camden, Ayr and Cambridge. The town of Dungog would be established in the Durham County, named after John George Lambton, First Earl of Durham (1792–1840).

In 1829, when the establishment of the nineteen counties was decreed to be the limits of settlement, the original Durham County was divided into two, with Gloucester County taking the eastern half of the original county. The dividing boundary was the Williams River, with Dungog lying just to the west of the river in County Durham. (Durham County in the UK was the place where Elizabeth’s family, the Raine family, had originated.)

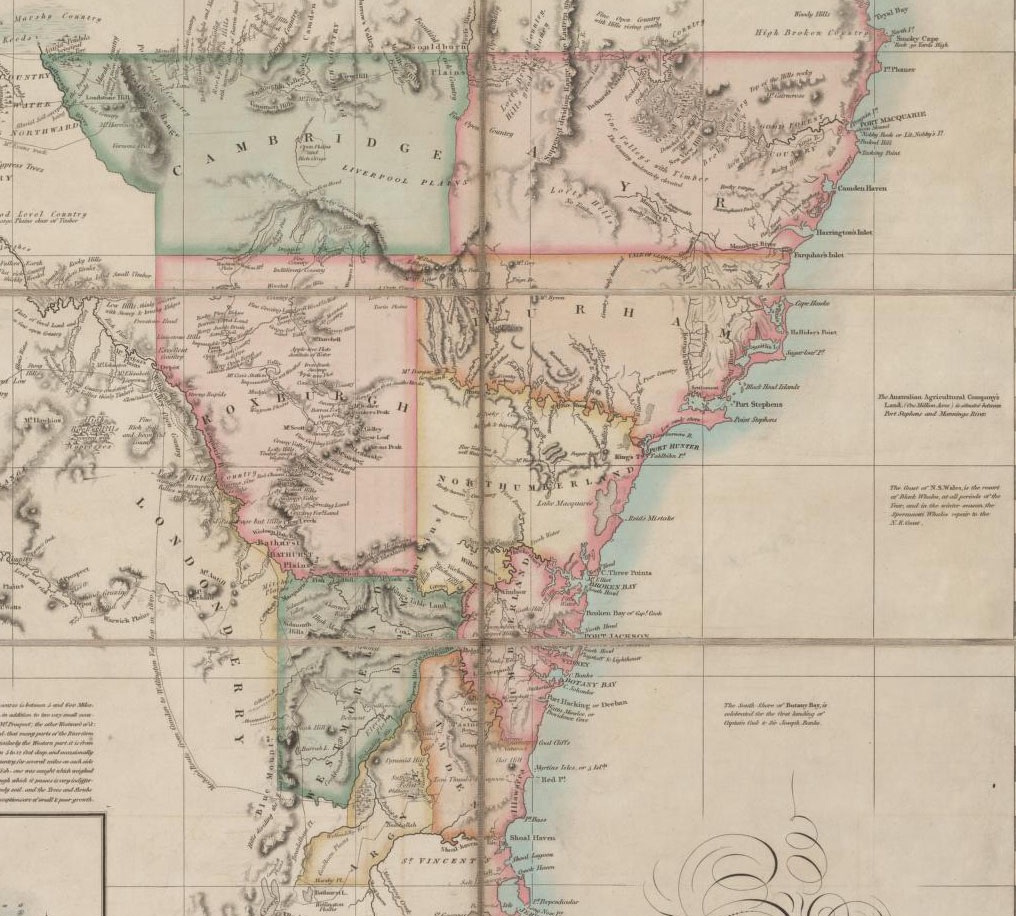

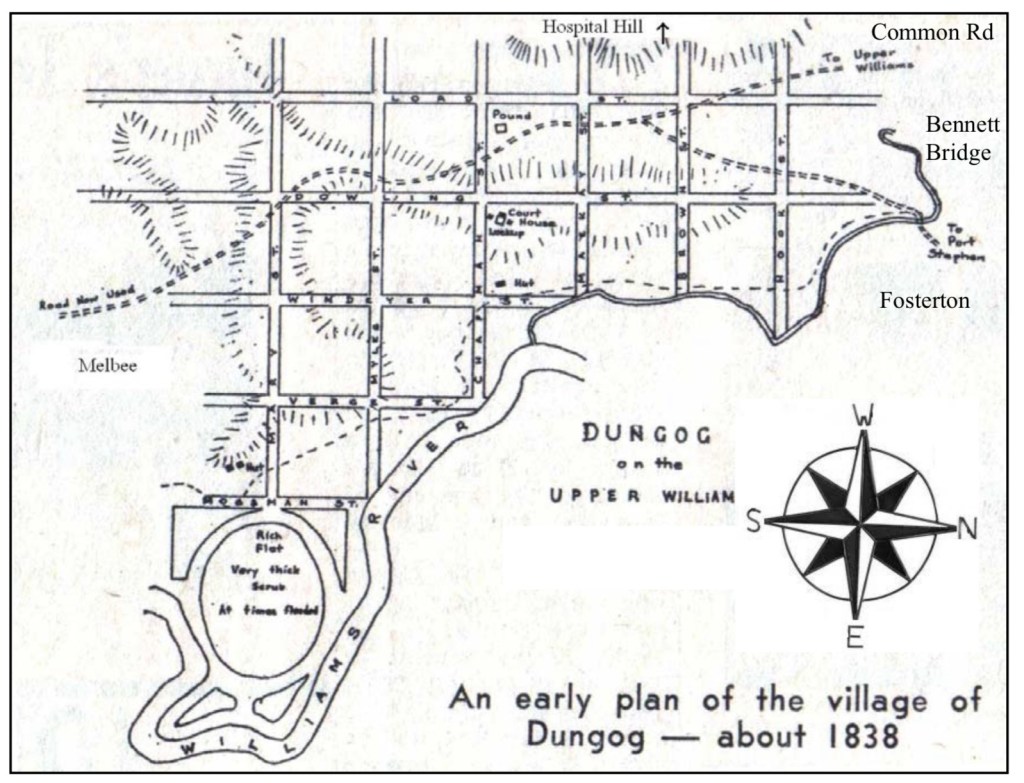

The Census of 1857 indicated that Dungog village had 25 houses and a population of 126 people. By 1861 the population had grown to 458 people. The town had begun some decades earlier, in 1838, when a fully surveyed plan of land for sale in Dungog was advertised in the Sydney Gazette. Initially, land was sold at a “Minimum price” of “£2 sterling per acre”. In 1839, a further parcel of half acre and other sized allotments were offered for sale at £4 per acre.

The 1838 plan can be seen as an example of the early colonial government’s attempts to create an English-style model of small villages and surrounding estates. The central area of the village was divided into a number of sections, each separated by a street. The first grant of land in the area had been made a decade earlier, to John Hooke, of Parramatta, in July 1828.

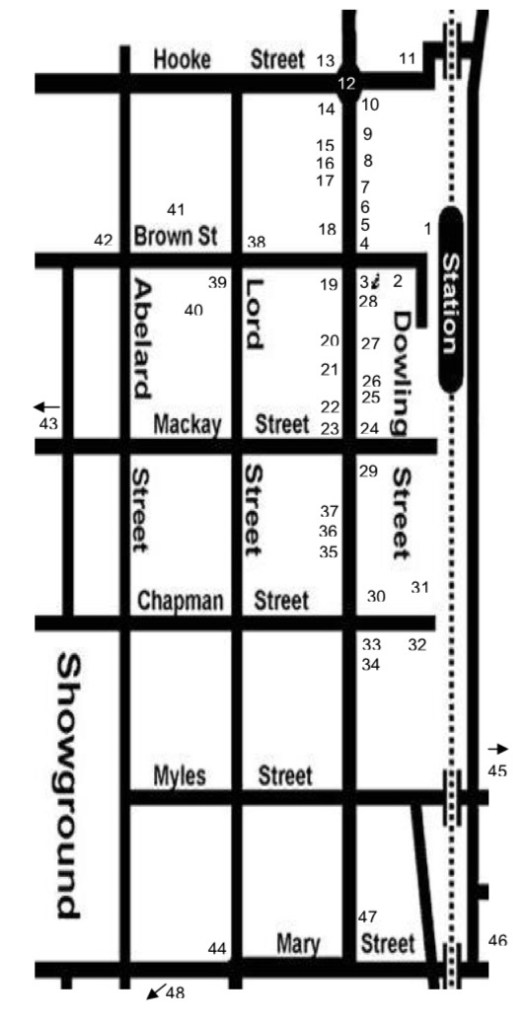

The block of land which we recently bought was originally bought under the system of colonial landholding by James Fawell on 9 May 1842. It cost him £4.0.0. The legal documentation identifies it as “Lot No. Seven Section No. Five in the Town of Dungog”. Section Five is the block bounded by Dowling, Brown, Lord, and Mackay Streets. Dowling St runs along the ridge beside the Williams River, and it developed early into the street of commerce for the town.

All four streets are named after early British settlers in the town. Dowling St bears the name of James Dowling, who was granted land in 1828. Dowling became the second Chief Justice of NSW, serving from 29 August 1837 to 27 September 1844, the day of his death.

The Hon. Sir James Dowling;

engraving by Henry Samuel Sade, c. 1860

Mackay St is named after D.F. Mackay, whose grant of 640 acres was made in 1829. Mackay took up the position of Superintendent of Prisoners and Public Works in Newcastle.

Lord St carries the name of John Lord, whose land (2560 acres) had been designated, in 1829, to be granted to Archibald Mosman; in 1836 it was re-allocated to John Lord. (Mosman did purchase land in the area in 1837, but sold it a year later and moved to Glen Innes.)

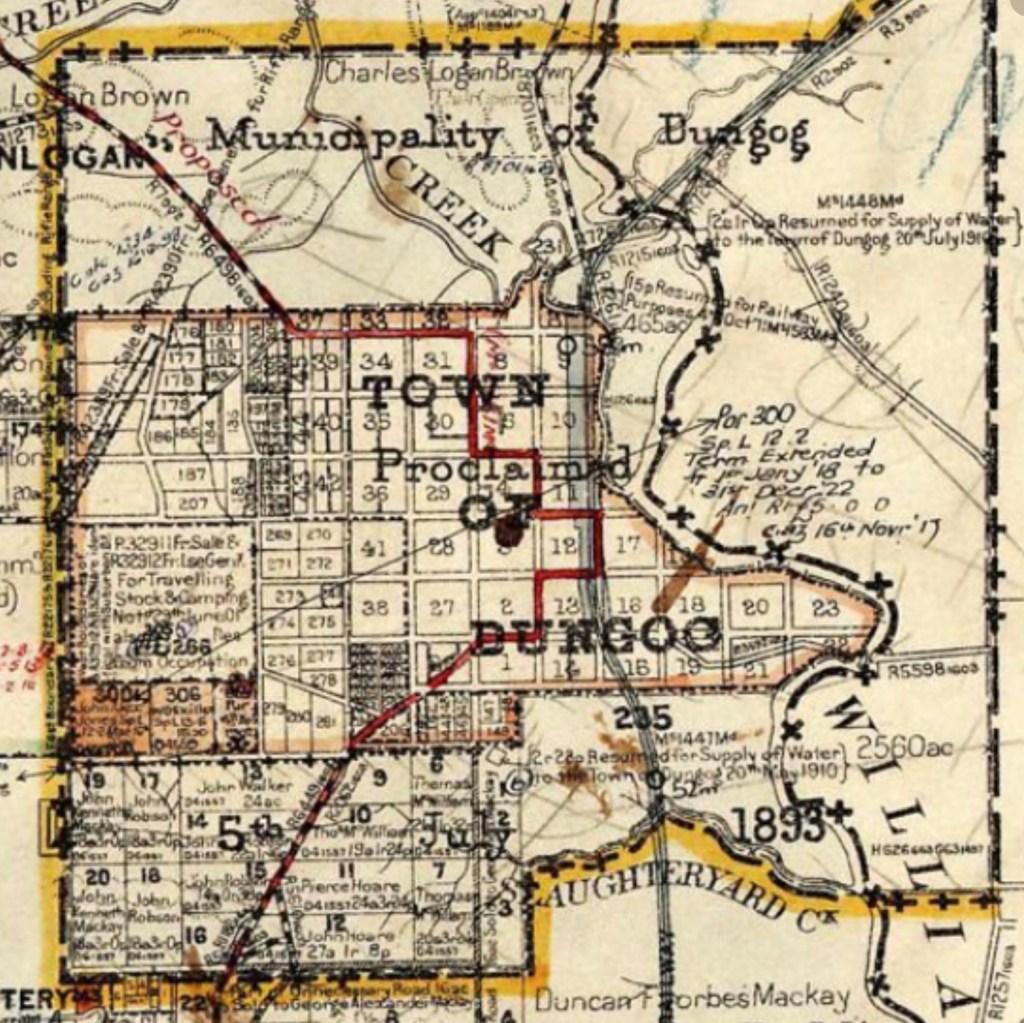

Brown Street, it seems, carries the name of one Crawford Logan Brown, a Scotsman who in 1829 had been granted 1280 acres at Dungog by the then Governor, Sir Ralph Darling.

Brown’s estate was named Cairnsmore. In 1836 he added to his grant with a purchase of 640 acres at a cost of £160. In addition to Cairnsmore at Williams River, Crawford L. Brown also owned land at Patrick Plains known as Blackford. He exemplifies the expansionary style of those privileged to obtain grants—and to have convict labour assigned to them—under the British colonial system.

Crawford Logan Brown served as a Magistrate at Dungog from 1845 until his death on 13th December 1859 in Dungog. An interesting—and startling—anecdote known about him is that in January 1846, whilst serving as Magistrate, he sentenced his own assigned servant Thomas Fry to two years in irons. This sentence was punishment for an assault that Fry had made on Brown himself!

of the Parish of Dungog, showing the grid plan

and numbered Lots in the Town of Dungog.

There will be more of the story told in a series of blogs to follow, focussing in on the history of the people, the land, and the house on the property that we currently occupy … … …

*****

See subsequent blogs at