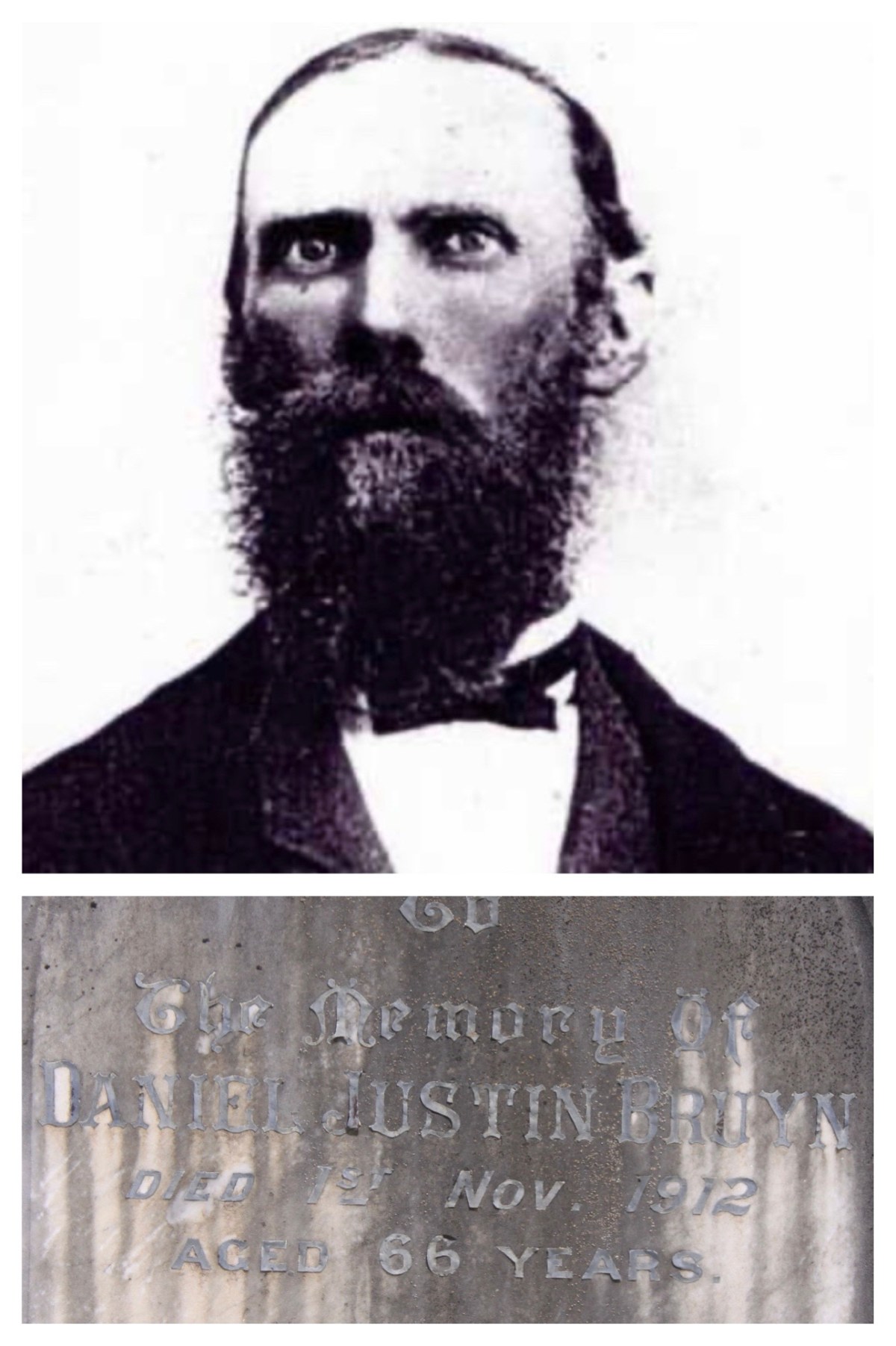

In exploring the history of the land and house which Elizabeth and I purchased in Dungog a few years ago, I have already noted the early landholders for this property, and investigated the life of Daniel and Sarah Bruyn and their family after Daniel purchased the land in 1858. When Daniel died intestate in 1882, all of his property was made over to his son, Daniel Justin Bryan, whose life we have considered. We turn now to his death.

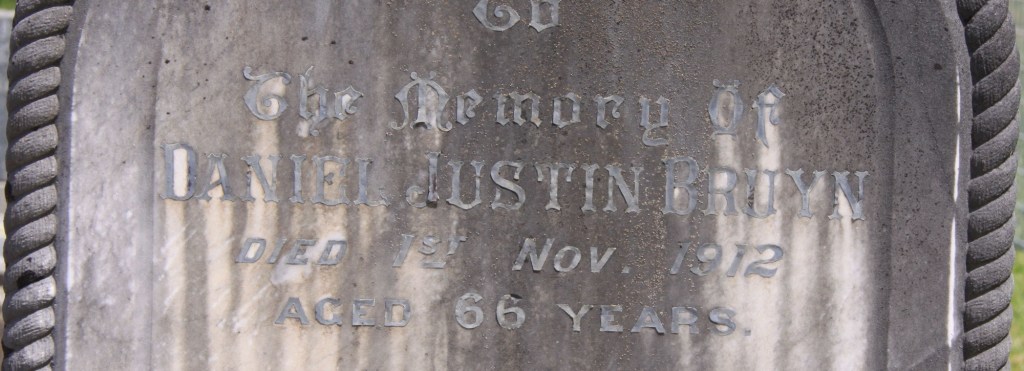

On 22 September 1886, Daniel Justin Bruyn had made his last Will and Testament “whereby he gave devised and bequeathed all his property of whatsoever nature and wheresoever situate to his sister Ellen Bruyn absolutely and appointed the said Ellen Bruyn the sole Executrix thereof”. On 1 November 1912 Daniel Justin Bruyn died, and that will came into effect.

A Coroner’s Inquest for Daniel Justyn Bruyn of Dungog was held by Walterus Le Brun Brown, J.P., on 2 November 1912. The report of the inquest notes that “cash or property possessed by deceased” was “probably over £10,000”. That equates to around $1.45 million in 2023.

Probate for the estate of Daniel Justin Bryan was granted on 26 February 1913. Daniel had never married and had no descendants; as his will prescribed, this collection of property and cash became the possession of Ellen Bruyn. That was a happy result for her in very sad circumstances. The death of Daniel Justin Bruyn, however had a deeper tragedy at its heart.

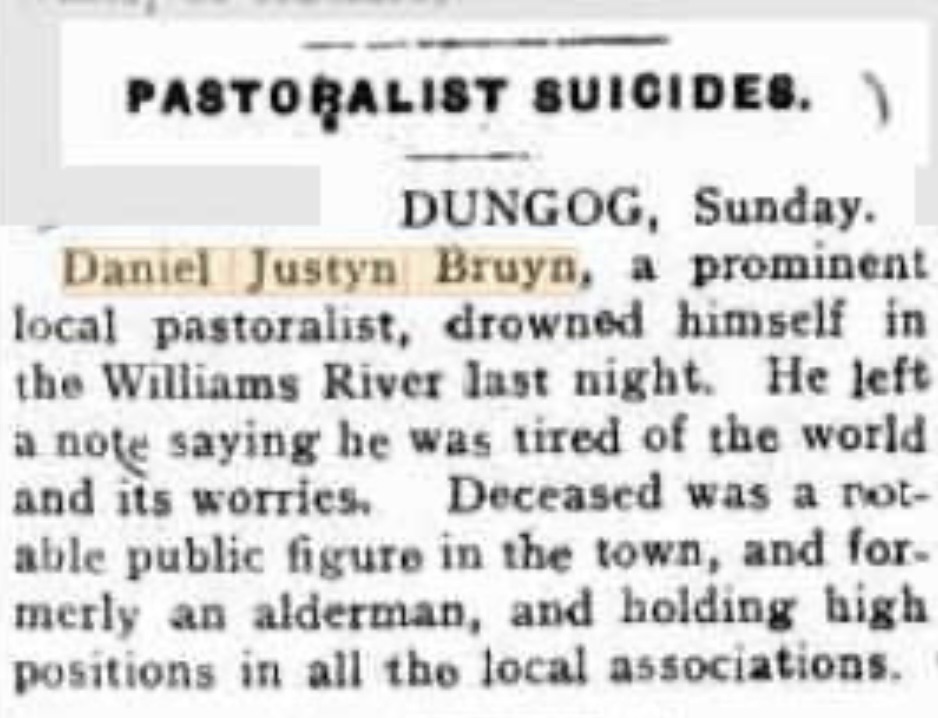

The Bathurst National Advocate stated the matter plainly, in a brief report published on Monday 4 November 1912, under the heading PASTORALIST SUICIDES: “Daniel Justin Bruyn, a prominent local pastoralist, drowned himself in the Williams River last night. He left a note saying he was tired of the world and its worries. Deceased was a notable public figure in the town, and formerly an alderman, and holding high positions in all the local associations.”

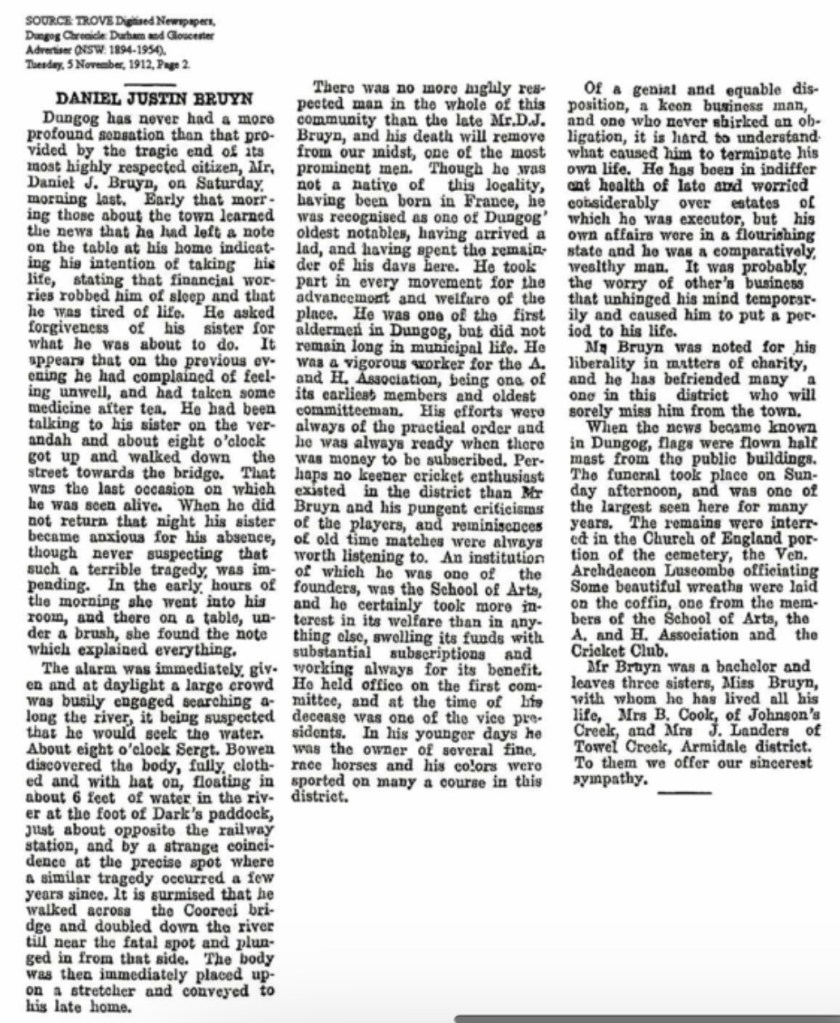

The next day, the Dungog Chronicle provided a much fuller obituary which provided details of the incident and demonstrated just how high a regard was had for Mr Bruyn in the town (Tuesday, 5 November, 1912, Page 2). “Dungog has never had a more profound sensation than that provided by the tragic end of its most highly respected citizen, Mr. Daniel J. Bruyn, on Saturday morning last”, it began.

“Early that morning those about the town learned the news that he had left a note on the table at his home indicating his intention of taking his life, stating that financial worries robbed him of sleep and that he was tired of life”, it continued. It then offered this sad commentary: “He asked forgiveness of his sister for what he was about to do.”

The Chronicle had been advised that “on the previous evening he had complained of feeling unwell, and had taken some medicine after tea. He had been talking to his sister on the verandah and about eight o’clock got up and walked down the street towards the bridge. That was the last occasion on which he was seen alive.”

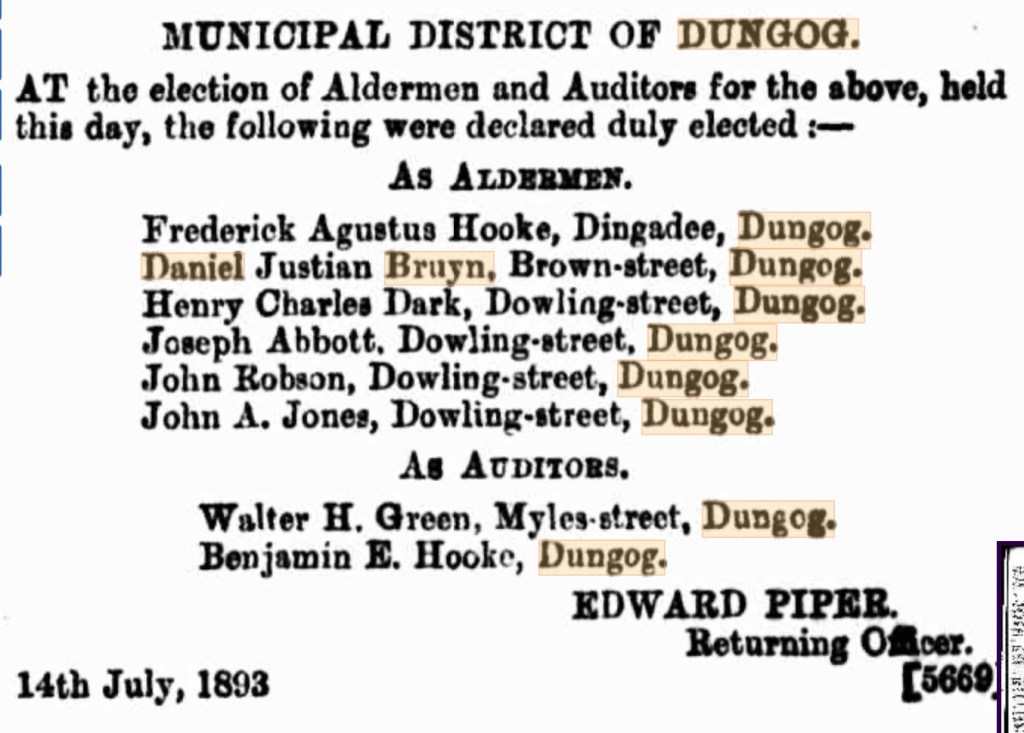

This report indicates that Daniel Bruyn did spend time living in the house at Brown Street with his sister, at least at this stage of his life. As both were unmarried, and as the house was ideally placed in the centre of town—next to Dark’s burgeoning general store on Dowling Street, near to the School of Arts where the Municipal Council met—it would make sense for Bruyn of Sugarloaf to have his base in Brown St for such town activities.

Indeed, as the report states, when his sister Ellen “became anxious for his absence … in the early hours of the morning she went into his room, and there on the table, under a brush, she found the note which explained everything”. It continues by noting that upon discovery of Mr. Bruyn’s body, he was “immediately placed upon a stretcher and conveyed to his late home”—that is, the residence in Brown St that he had so recently left.

And, as we have seen, when he was elected to Dungog Council in 1893, his residence is listed as Brown Street. (Michael Williams, in his extensive survey of the historic buildings of Dungog, notes that street numbers were not used until the 1960s; see Ah! Dungog, 2011, p.11.)

The detailed report of Daniel Bruyn’s death in the Dungog Chronicle of 5 November 1912 noted that once his note was discovered and the alarm was raised, “at daylight a large crowd was busily engaged in searching along the river, it being suspected that he would seek the water.”

Sure enough, the report continues, “about eight o’clock Sergt. Bowen discovered the body, fully clothed and with hat on, floating in about 6 feet of water in the river at the foot of Dark’s paddock, just about opposite the railway station, and by a strange coincidence at the precise spot where a similar tragedy occurred a few years since. It is surmised that he walked across the Cooreei bridge and doubled down the river till near the fatal spot and plunged in from that side.” (The Cooreei Bridge crosses the Williams River about a kilometre out of town, on the road that connects Dungog with Stroud.)

The report continues with words that emphasise the regard felt for the deceased: “There was no more highly respected man in the whole of this community than the late Mr.D.J. Bruyn, and his death will remove from our midst, one of the most prominent men … he was recognised as one of Dungog’s notables.” Then, musing on the manner of his death, it opines, “of a genial and equable disposition, a keen business man, and one who never shirked an obligation, it is hard to understand what caused him to terminate his own life.”

the Dungog Chronicle just four days after his death

The report further offers comments on the character of Mr. Bruyn: he was “noted for his liberality in matters of charity, and he has befriended many a one in this district who will sorely miss him from the town.” The report notes the fitting tribute paid to Daniel Justin Bruyn: “when the news begame known in Dungog, flags were flown half mast from the public buildings”.

In pondering a possible reason for this suicide, the article offers a hypothesis, noting that Daniel Bruyn “has been in indifferent health of late and worried considerably over estates of which he was executor, but his own affairs were in a flourishing state and he was a comparatively wealthy man. It was probably the worry of other’s business that unhinged his mind temporarily and caused him to put a period to his life.” The truth of this hypothesis, however, will never be able to be ascertained.

A correspondent in the Maitland Daily Mercury on Wednesday 6 Nov 1912, p.2, further expresses the dismay of the locals at the news of Daniel’s death: “to say that Dungog and district were struck dumb when it became known that Mr. Daniel Justin Bruyn had left a note expressing his intention to end his life, is putting the truth very mildly. The deceased was about the last person anyone would have expected to do such an act. He was a very quiet man of a retiring disposition, and as far as an onlooker could see had less worry than most people. He was more universally trusted than most men, as proved by the number of wills in which he was appointed an executor, and it is thought that his troubles were not his own, but were those which he voluntarily shouldered for others.”

Of the funeral of Daniel Justin Bruyn, the Dungog Chronicle notes that, as might be expected, it was “one of the largest seen here for many years”. The Anglican minister, the Ven. Archdeacon Luscombe, officiated, and wreaths were laid on the coffin from organisations including the School of Arts, the A. and H. Association, and the Cricket Club. Three of his sisters remained: Ellen Bruyn in Brown St, Elizabeth Cook of Johnson’s Creek north of Stroud Road, and Sarah Landers of Towel Creek in the Armidale district.

Our particular story will continue with Daniel’s sister, Ellen Bruyn … … …

For earlier posts, see

For the story of Ellen Bruyn, see