This year, 2025, marks 1700 years since the Council of Nicaea was held. The Council was called by the Roman emperor Constantine; he invited bishops (local church leaders) from around the Roman Empire, to meet in in his imperial palace in Nicaea, Bythinia (in modern-day Turkey).

Those bishops met in council from May to July in 325CE. The traditional account of the Council was that 318 bishops attended; most came from eastern churches, with only a small number from western churches. Despite this lopsided representation, the council is known as the first of a series of Ecumenical Councils, allegedly representing the worldwide church.

The end result of the Council was a Creed which bears the name of the meeting place: the Nicene Creed. Half a century later, this creed was expanded at the Council of Constantinople in 381 CE—another council called by the Roman emperor, who was by then Theodosius.

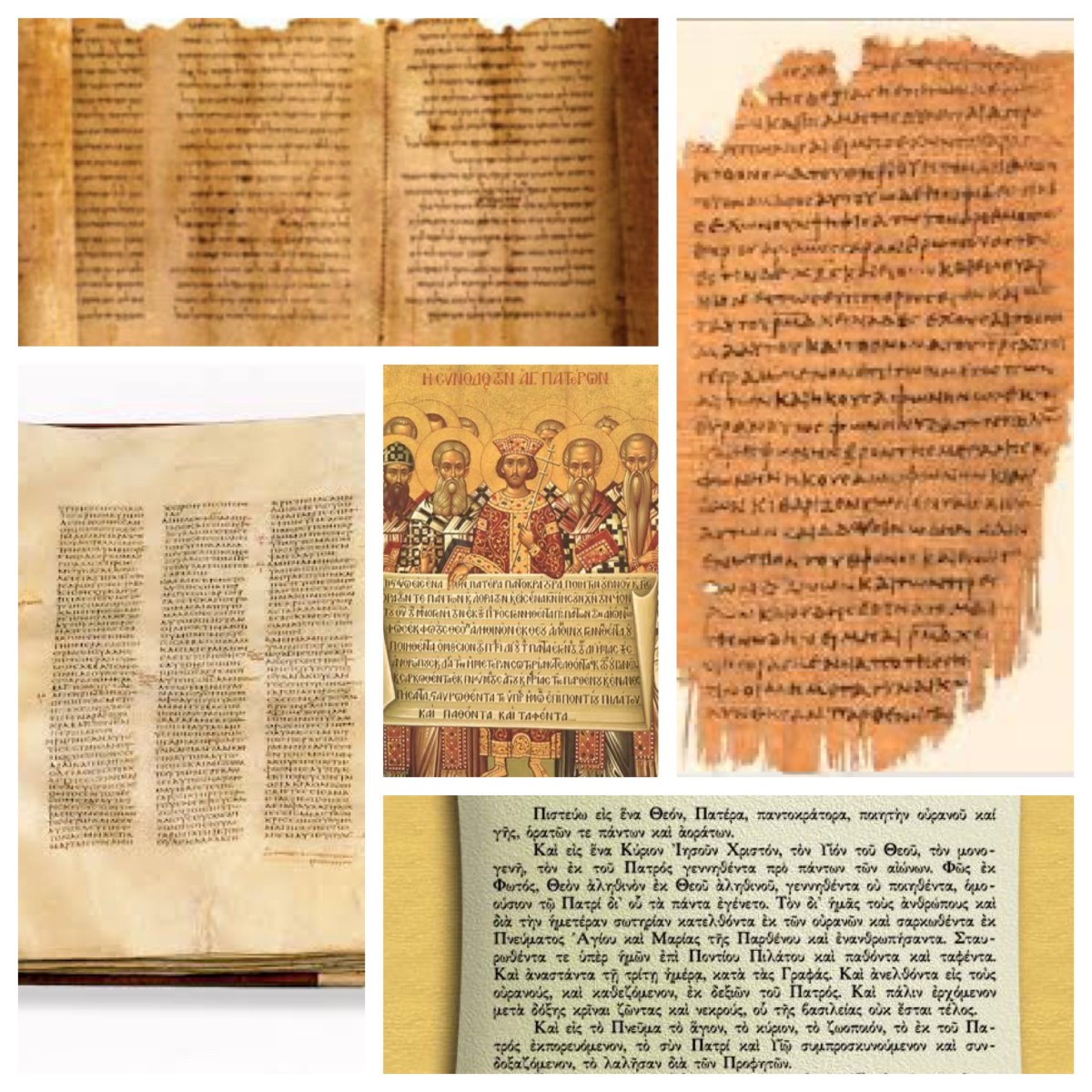

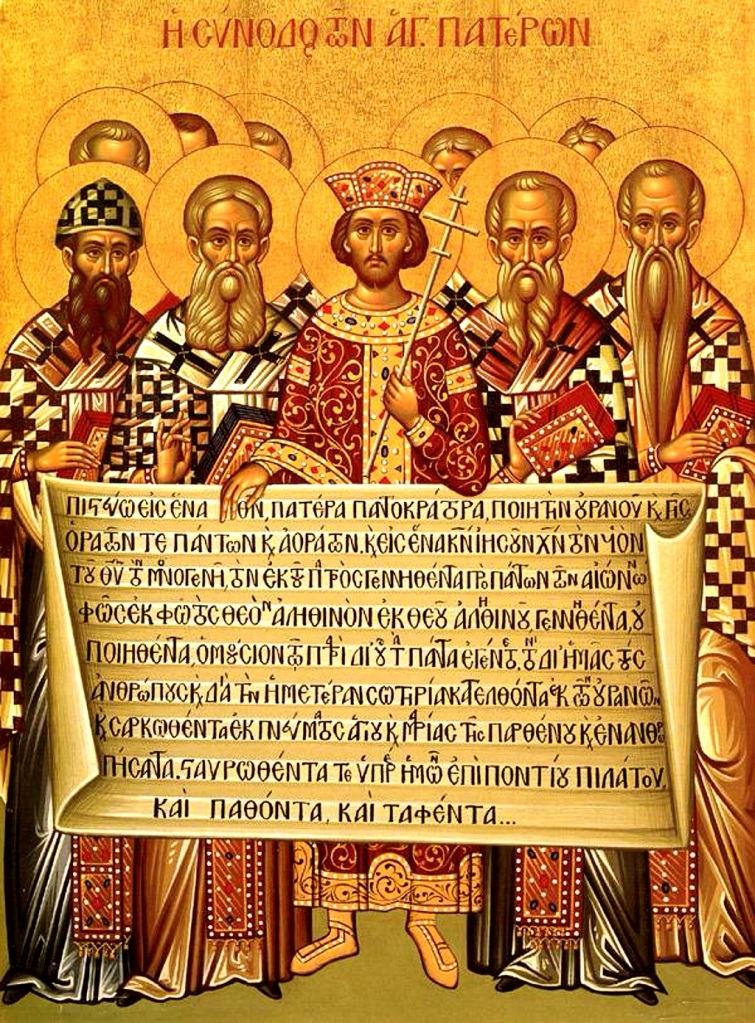

Icon depicting Constantine the Great, accompanied

by some of the bishops of the First Council of Nicaea (325),

holding the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed of 381.

First line of main text in Greek: Πιστεύω εἰς ἕνα Θ[εό]ν, πατέρα παντοκράτορα, ποιητὴν οὐρανοῦ κ[αὶ] γῆς. Translation: “I believe in one God, the Father the Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth.”

What came from this council was the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed came to be widely adopted as a foundational expression of the Christian faith. Although various elements in the creed have been interpreted in a variety of ways, it has featured in the ancient churches of the East and the West, and in more recent centuries of the North and South.

Where does this creed come from? There are some passages in scripture which have a “credal-like” quality. Might consideration of those sections of scripture lead us to understand what drove those fourth century bishops to formulate such a creed? I begin by considering two relevant passages where the early “credal-like” statement is very short.

First: Corinth

The starting point for me would be in an early New Testament document, the first (extant) letter to the Corinthians, which Paul and Sosthenes wrote to the community of faith in Corinth in the middle of the fifth century (as we count time).

Paul and Sosthenes wrote addressing a situation where factionalism, dubious morality, unrestrained chaos in worship, theological divisions, and differing approaches to cultural practices threatened the very existence of a cohesive faith community. Seeking a common denominator that all could commit to and focus on as their bedrock, they proposed “Jesus is Lord” (1 Cor 12:3) as a foundational affirmation.

This confession describes Jesus using a term with significance in Hebrew Scripture (“who is God except the Lord?”, Ps 18:31). Later commentators have observed that within the Roman imperial context, the Emperor functioned in the manner of a Lord—although the precise claim that Christians were forced to say “Caesar is Lord” is not substantiated by any extant ancient document.

So the first credal statement in the early years of the movement that Jesus initiated was born in the midst of conflict, as a way to bring cohesion and unity. We know, however, from subsequent correspondence involving believers in Corinth (letters known as 2 Corinthians and 1 Clement) that this rhetorical effort was a failure; conflict and divisions continued within the community throughout the remainder of the first century CE. Later, at the Council of Nicaea, the tile “Lord” was applied both to Jesus (“the m

Next: Caesarea Philippi

Nevertheless, other writers in that early Jesus movement adopted a similar strategy, writing short, succinct statements which they believed would serve to unite disparate factions. In the earliest extant written account of the public activities of Jesus, Simon Peter tells Jesus, “you are the Messiah” (Mark 8:29). This was a simple Jewish affirmation, referring to one who had been anointed for a task as a prophet. We have indications of this for Elisha (1 Ki 19:16) and for an unnamed post-exilic prophet (Isa 61:1).

Anointing was also used in the installation of kings: Saul (1 Sam 10:1–2; 15:7), David (1 Sam 16:13, in Israel; 2 Sam 2:1–7, in Judah; 5:1–5, 17; 12:7; 23:1, over all Israel), Solomon (1 Ki 1:38–40, 45), Jehu (2 Ki 9:1–3, 6, 12), Joash (2 Ki 11:12), Jehoahaz (2 Ki 23:30), and all of David’s descendants (Ps 18:50; 45:7; 89:20–21, 38–39, 49–51; 132:10, 17).

Drawing from this Jewish heritage to make this confession makes sense, given that Jesus and Simon Peter were both Jewish men, and the incident that provoked this response by Peter took place on Jewish land—amongst “the villages of Caesarea Philippi”, on the northernmost edge of Israel.

A later writer took this confession—another very early creed, if you like—and expanded it just a little. “You are the Messiah, the Son of the living God”, Peter declares, in Matthew’s version of the incident (Matt 16:16).

Just as “Messiah” was a well-known term in Hebrew Scripture, so too “living God” is applied to the God of Israel in narratives (Deut 5:26; Josh 3:10; 1 Sam 17:26, 36; 2 Ki 19:4, 16, repeated at Isa 37:4, 16), prophets (Jer 10:10; 23:36; Dan 6:20, 26; Hos 1:10), and in psalms (Ps 42:2; 82:2). The use of a scriptural title to describe the significance of Jesus is thus an early credal affirmation.

The scriptural title of Messiah appears in the Nicene Creed in the Greek equivalent, Christ, when the second part of the creed is introduced: “We believe in one Lord Jesus Christ”, before proceeding to use other terms for the exalted nature of Jesus as “eternally begotten of the Father; God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God; begotten not made, one in being with the Father”. These phrases are taken from parts of scripture that are not credal as such, but which reflect on the nature of Jesus in a developed theological manner. We will explore them in later posts.

*****

See