This year, 2025, marks 1700 years since the Council of Nicaea was held. I am posting a series of blogs about the way that the New Testament texts contributed (or didn’t contribute) to the credal formulation that emerged from that First Ecumenical Council, as it is often styled. The first post explored some one-phrase credal-like affirmations in Paul and the Synoptic Gospels. In this post the focus is on a section of the letter to the Colossians.

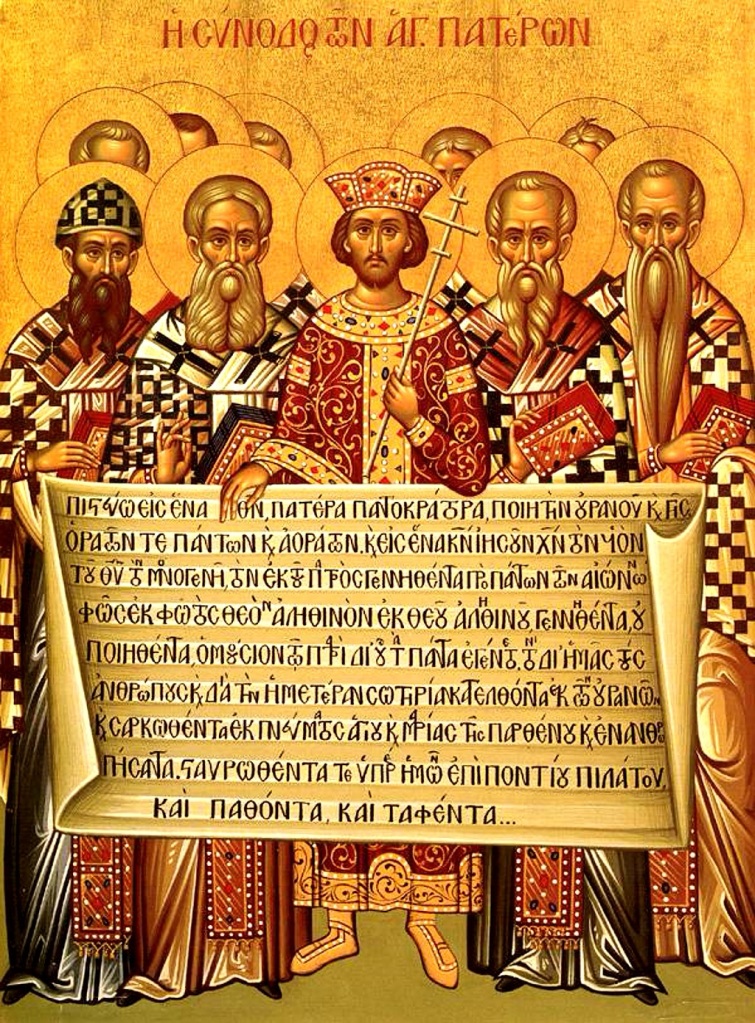

Icon depicting Constantine the Great, accompanied

by some of the bishops of the First Council of Nicaea (325),

holding the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed of 381.

First line of main text in Greek: Πιστεύω εἰς ἕνα Θ[εό]ν, πατέρα παντοκράτορα, ποιητὴν οὐρανοῦ κ[αὶ] γῆς. Translation: “I believe in one God, the Father the Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth.”

Alongside the very short credal affirmations found in 1 Corinthians and the Caesarea Philippi scene in the Synoptic Gospels (see first post), another place in the New Testament where language from the scriptural traditions of Judaism is used to shape an affirmation of what is believed about Jesus is in the first chapter of the letter to the Colossians.

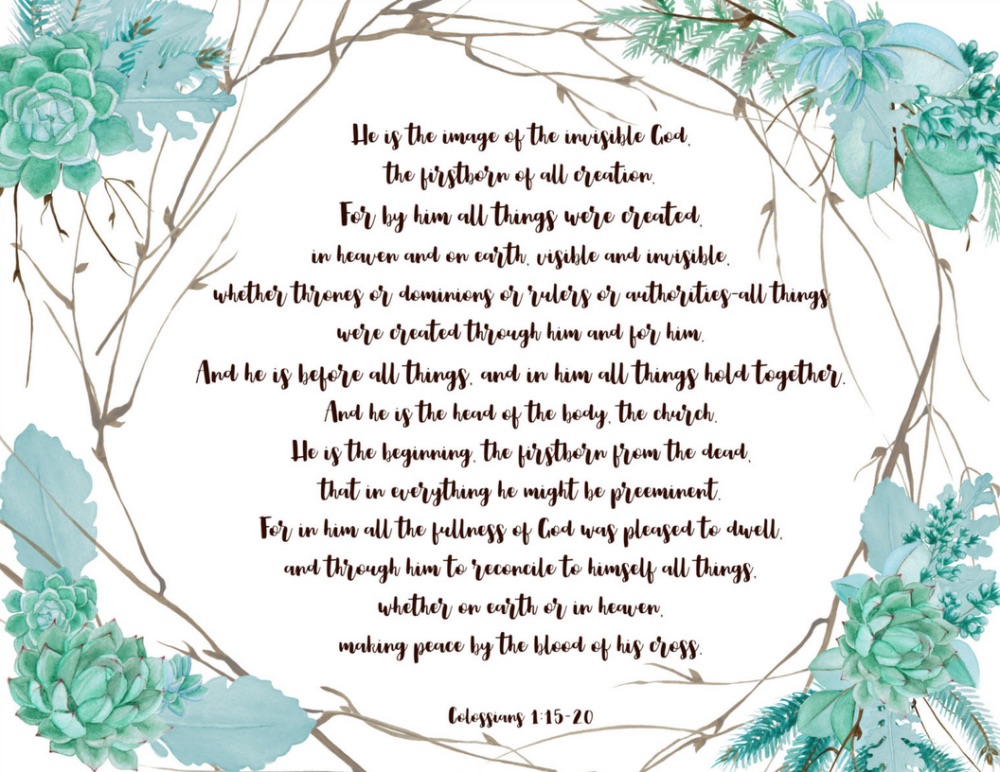

Col 1:15–20 provides us with a more complex example of what we might consider to be a creed “before Nicaea”. It provides some of the material for the developed theological confession of Jesus that the Nicene Creed uses (as just noted).

The author of this letter (claiming to be Paul, 1:1, although I am not convinced it was actually by him) begins with the expected words of greeting (1:1–2) and prayer of thanksgiving (1:3–8). The prayer morphs into a prayer of intercession for the Colossians (1:9–12), cycling back into an expression of thanks to “the Father” (1:12) for what he has done through “his beloved Son” (1:13–14).

This thanksgiving then morphs seamlessly (in the original Greek, there is no sentence break) into an extended affirmation about Jesus, “the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation … the head of the body, the church … the beginning, the firstborn from the dead …[in whom] all the fullness of God was pleased to dwell” (1:15–20).

This is quite an extension to the expression of thanks; the sentence in Greek actually begins in v.9 and continues through multiple subordinate clauses to v.20! It offers a relatively early consideration of “the person and work of Jesus Christ”, as later systematic theology writers would label it. It is a complex and intricate affirmation of faith.

The main thrust of this early creed, if we can call it that, can best be understood by giving consideration to the way this it draws on Jewish elements—specifically, the Wisdom material found in parts of Hebrew Scripture. Jesus is portrayed very much in the manner of Lady Wisdom, as we encounter her in scripture in Proverbs 8, and then in the deuterocanonical works of Ben Sirach (Ecclesiaticus) and the Wisdom of Solomon.

In Colossians, of course, the attributes of the female Wisdom are applied directly to the male Jesus. Jesus is here described as the agent of God’s creative powers: “in him all things in heaven and on earth were created … all things have been created through him and for him” (Col 1:16). In the same way, in Proverbs Wisdom herself is said to have declared that “ages ago I was set up, at the first, before the beginning of the earth … when [the Lord] established the heavens, I was there … when he marked out the foundations of the earth, then I was beside him, like a master worker” (Prov 8:22–31).

In the Wisdom of Solomon, Wisdom is described as “the fashioner of all things” (Wisd Sol 7:22), “a breath of the power of God” who “pervades and penetrates all things”(7:24–25), who was “present when you [God] made the world” (9:9), whose “immortal spirit is in all things” (12:1).

In Ben Sirach, Jesus, son of Sirach, declares that “Wisdom was created before all other things” (Sir 1:4), that at the very first she “came forth from the mouth of the Most High, and covered the earth like a mist” (Sir 24:3), and “compassed the vault of heaven and traversed the depths of the abyss” (24:5) as she undertook her creative works, distinguishing one day from another and appointing “the different seasons and festivals” (33:7–8).

Jesus Christ, as the one who is “before all things” (Col 1:17), reiterates what Wisdom declared, that “before the mountains had been shaped, before the hills, I was brought forth—when [the Lord] had not yet made earth and fields, or the world’s first bits of soil” (Prov 8:25–26).

So Jesus is the one who has “first place in everything” (Col 1:18), just as the works of Wisdom can be traced “from the beginning of creation” (Wisdom Sol 6:22). The importance of these Wisdom writings for what is stated in Col 1 is clear. (The same writings underpin the theological affirmations made about Jesus in Heb 1:1–4 and John 1:1–18; on which, see later posts.)

The passage in Colossians also indicates that believers are “transferred … into the kingdom of [God’s] beloved son” (Col 1:13); they are rescued (1:13) and redeemed (1:14) by the work of Jesus. In similar fashion, the Wisdom of Solomon contains a long section praising Wisdom who was actively involved in human affairs from when “she delivered him [Adam] from his transgression” (Wisd Sol 10:1), saved the people at the Exodus, and guided the Conquest and settlement in the land. It was Wisdom who punished the Canaanites (12:3–11), sinful Israelites (12:19–22), and the Egyptians (12:23–27), as well as all idolators (13:1—14:31).

A similarly lengthy poem praising the works of Wisdom occurs in chapters 44 to 50 of Ben Sirach, extending all to the way to Simon, son of Onias (high priest in the early C3rd BCE), just as the creative work of Jesus is noted in the Nicene Creed (“through him all things were made”, so his salvific work is also briefly described (“for us [all] and for our salvation he came down from heaven“).

These fleeting references draw on the way in which scripture has used the Wisdom literature— although, of course, all four Gospels and many Epistles note the forgiving, saving, delivering work of Jesus. It is, in fact, the bedrock of the developing patristic theology of the time between the New Testament and the early Ecumenical Councils.

*****

See the first post at

and subsequent posts at