This year, 2025, marks 1700 years since the Council of Nicaea was held. I am posting a series of blogs about the way that the New Testament texts contributed (or didn’t contribute) to the formulation that emerged from that First Ecumenical Council, as it is often styled. The first post explored some one-phrase credal-like affirmations in Paul and the Synoptic Gospels; the second post examined a section of the letter to the Colossians.

Icon depicting Constantine the Great, accompanied

by some of the bishops of the First Council of Nicaea (325),

holding the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed of 381.

First line of main text in Greek: Πιστεύω εἰς ἕνα Θ[εό]ν, πατέρα παντοκράτορα, ποιητὴν οὐρανοῦ κ[αὶ] γῆς. Translation: “I believe in one God, the Father the Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth.”

We have looked at 1 Corinthians and a scene in the Synoptic Gospels, as well as a passage in Colossians that draws significantly on Wisdom texts to explain the importance of Jesus. There are other places in the New Testament which make quite explicit use of the Wisdom literature as they take ideas about Lady Wisdom—as co-creator with God, as revealed and teacher of things from God—and apply them directly to Jesus. In the course of doing this, of course, Wisdom loses her feminine identity, as it is subsumed in the masculine figure of Jesus (as we have already seen in Colossians). In the first few centuries of the church, Patriarchy Rules!!

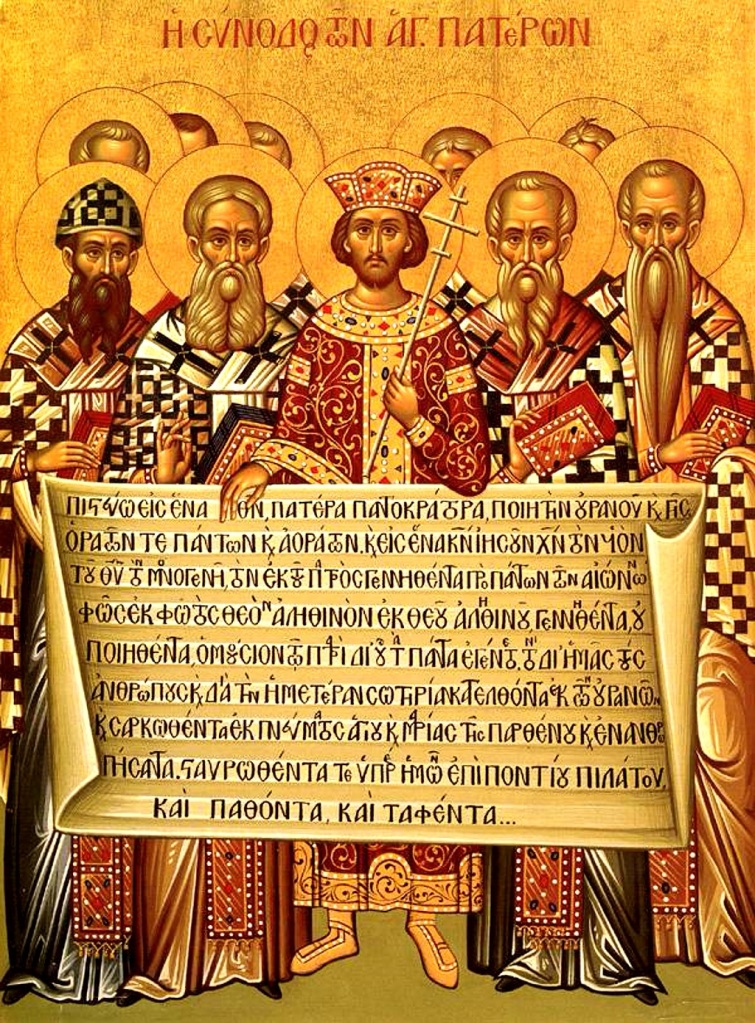

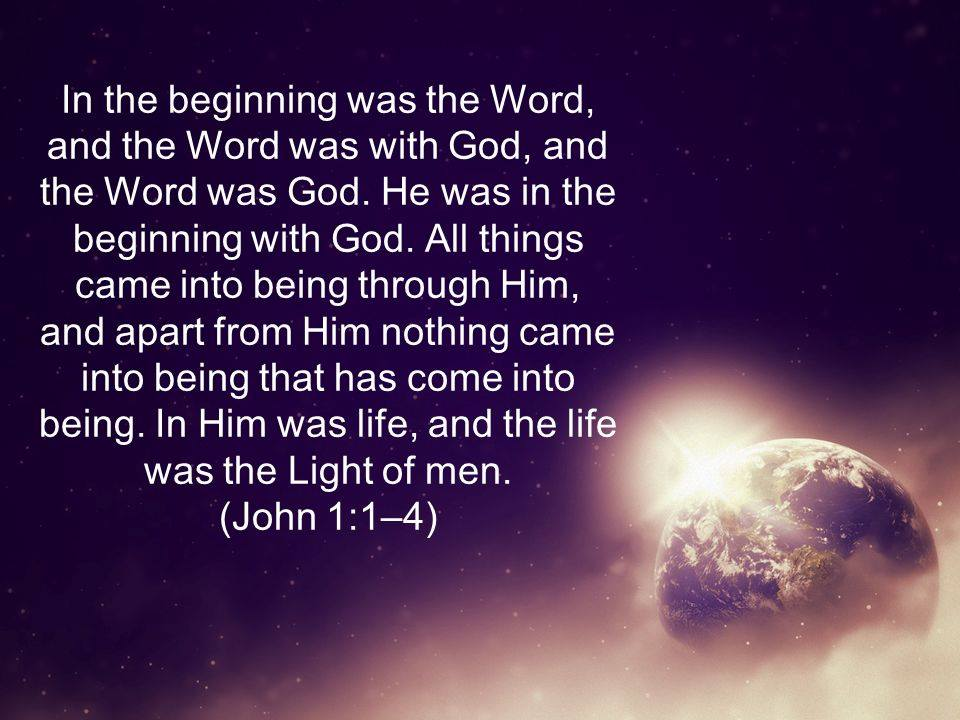

The two places where this use of Wisdom motifs can be seen are in the opening verses of the letter to the Hebrews (Heb 1:1–4) and in the majestic poetic prologue to John’s Gospel (John 1:1–18). In both cases, Jesus is the speaking forth of God, as Wisdom was; and in both cases, Jesus is seen to have been present with God at the creation of the world, and active in the creative process, as Wisdom was.

In the prologue to Hebrews, its anonymous author declares that God, who “long ago spoke to our ancestors in many and various ways by the prophets” has more recently, “in these last days … spoken to us by a Son” (Heb 1:1), one who “sustains all things by his powerful word” (Heb 1:3). In the prologue to the fourth Gospel, the John who is attributed as its author similarly declares that the pre–existent Logos (John 1:1), revealed as “the Word [who] became flesh” (John 1:14), was the one who “makes God known” (John 1: 17–18).

These statements mirror the affirmations made in earlier Jewish texts about Wisdom. According to Proverbs, her declaration is very public: “Wisdom cries out in the street; in the squares she raises her voice; at the busiest corner she cries out; at the entrance of the city gates she speaks” (Prov 1:20–22; see also 8:1–3). What she speaks bears the mark of God’s teachings; her words are noble, true, what is right, and completely righteous (Prov 8:6–8).

As she speaks, teaching her children, she “gives help to those who seek her” (Sir 4:11). As he writes of Wisdom in a later time, Ben Sirach describes how “in the assembly of the Most High she opens her mouth, and in the presence of his hosts she tells of her glory” (24:1–2). In her words is wisdom for life and instruction for souls (51:25–26).

The motif of “word” then runs consistently throughout the fourth Gospel: Jesus “speaks the words of God” (John 3:34; 8:47; 12:50; 14:8–10; 17:14), gives teaching which is “from God” (7:16–18; 14:24; 17:7–8), makes known “everything that I have heard from my Father” (15:15), utters words of “spirit and life” (6:63, 67). For the author of this Gospel, Jesus is, indeed, the Word who was always with God (1:1). It is a striking appropriation of the role that Wisdom has played, according to these earlier texts.

Turning back to the prologue to this Gospel, we note that Jesus is portrayed not only as the speaking-forth of God as “the word”, but also as the one who manifests glory, “the glory as of a father’s only son, full of grace and truth” (John 1:14). Indeed, the glory shown by Jesus had been evident centuries earlier, as was attested in the words of Isaiah (John 12:41).

This claim about Jesus resonates with the description of Wisdom as “a pure emanation of the glory of the Almighty” (Wisdom Sol 7:25). Indeed, the motif of “glory” hearkens back to wilderness stories in Exodus and Numbers and receives its clearest New Testament expression, in relation to Jesus, at Col 1:15–20, as we have previously seen.

The imagery of “glory” is taken up and then intensified in the prologue of Hebrews, where Jesus is seen as “the reflection of God’s glory and the exact imprint of God’s very being” (Heb 1:3). Indeed the Wisdom of Solomon, the figure of Wisdom was portrayed in majestic terms as “a breath of the power of God … a reflection of eternal light, a spotless mirror of the working of God, and an image of [God’s] goodness” (Wisd Sol 7:25–26). Hebrews itself echoes the language of the Wisdom of Solomon.

The person of Wisdom, a reflection of God, the exact imprint of God, emanating directly from the Almighty, had earlier been described in Proverbs as being “set up, at the first, before the beginning of the earth” (Prov 8:30), taking part with the deity in the acts of creation. The poetry builds through repetition and ever-expanding circle of influence; when “he established the heavens, I was there”, she says; “when he drew a circle on the face of the deep, when he made firm the skies above, when he established the fountains of the deep, when he assigned to the sea its limit … when he marked out the foundations of the earth” (Prov 8:27–29). In all these acts of creation, Wisdom was beside the Lord, “daily his delight, rejoicing before him always, rejoicing in his inhabited world and delighting in the human race” (Prov 8:30–31).

This affirmation leads on to the claim that Wisdom “pervades and penetrates all things” (Wisd Sol 7:24) and “renews all things … [she] passes into holy souls and makes them friends of God, and prophets” (Wisd Sol 7:27). She “reaches mightily from one end of the earth to the other, and she orders all things well” (Wisd Sol 8:1). Likewise, Jesus son of Sirach writes in a song of Wisdom that she “came forth from the mouth of the Most High, and covered the earth like a mist” (Sir 24:3), expanding on this in a sequence of grand claims: “I dwelt in the highest heavens, and my throne was in a pillar of cloud. Alone I compassed the vault of heaven and traversed the depths of the abyss. Over waves of the sea, over all the earth, and over every people and nation I have held sway.” (Sir 24:6).

And so, just as Wisdom has been with God since the beginning, working with God in every phase of creation, the claim is then made for Jesus, the Word, that he was “in the beginning with God” (John 1:2), and that “all things came into being through him, and without him not one thing came into being” (John 1:3). The co-creative role of Wisdom has been claimed for the Word, the sole creator of the world.

And, indeed, the presence of this Word throughout all the world is expressed in another characteristic Johannine image, as the Word comes as “the light of all people” a light which “shines in the darkness”, the “true light” which “enlightens everyone” (John 1:4–5, 9). This is picked up with focussed clarity in the claims later put onto the lips of Jesus, “I am the light of the world” (8:12; 9:5; and see 12:35–36, 46).

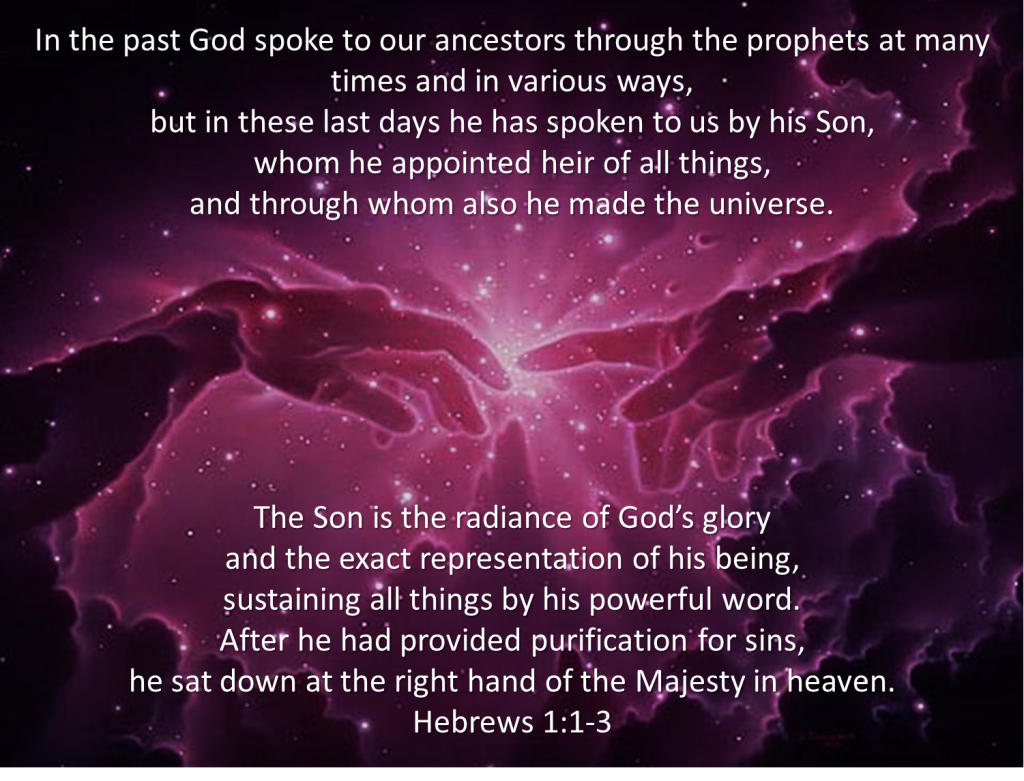

So there is a clear and direct trajectory in Jewish documents, from the scriptural text of Proverbs, through the Intertestamental texts of the Wisdom of Solomon and Ben Sirach, into the New Testament texts as indicated. And from there, into the credal structures of the emerging patristic church, affirming that belief in Jesus entails acknowledgement that he is “the only Son of God, eternally begotten of the Father, God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God, begotten, not made, of one being with the Father”. Whilst some of the precise terminology and its relationship to the biblical texts might be debated, the line of development (from Wisdom, to Word, to creed) is clear.

All of which makes it rather striking that so much of the second section of the Nicene Creed is devoted to articulating a line of thought that draws from a relatively small collection of biblical texts, whilst almost completely ignoring the vast majority of what the New Testament bears witness to: the life of Jesus, his teachings, his fervent sense of justice, his passionate desire to reform and renew Judaism, and the miraculous deeds attributed to him.

The richness of meaning and wideness of scope of so many stories and teachings and passages within the New Testament is reduced and narrowed to a small collection of words in the creed. The creed itself is largely focussed on matters heavenly, speculative, and philosophical. Such is the nature of the Nicene Creed.

*****

See earlier posts at

and subsequent posts at