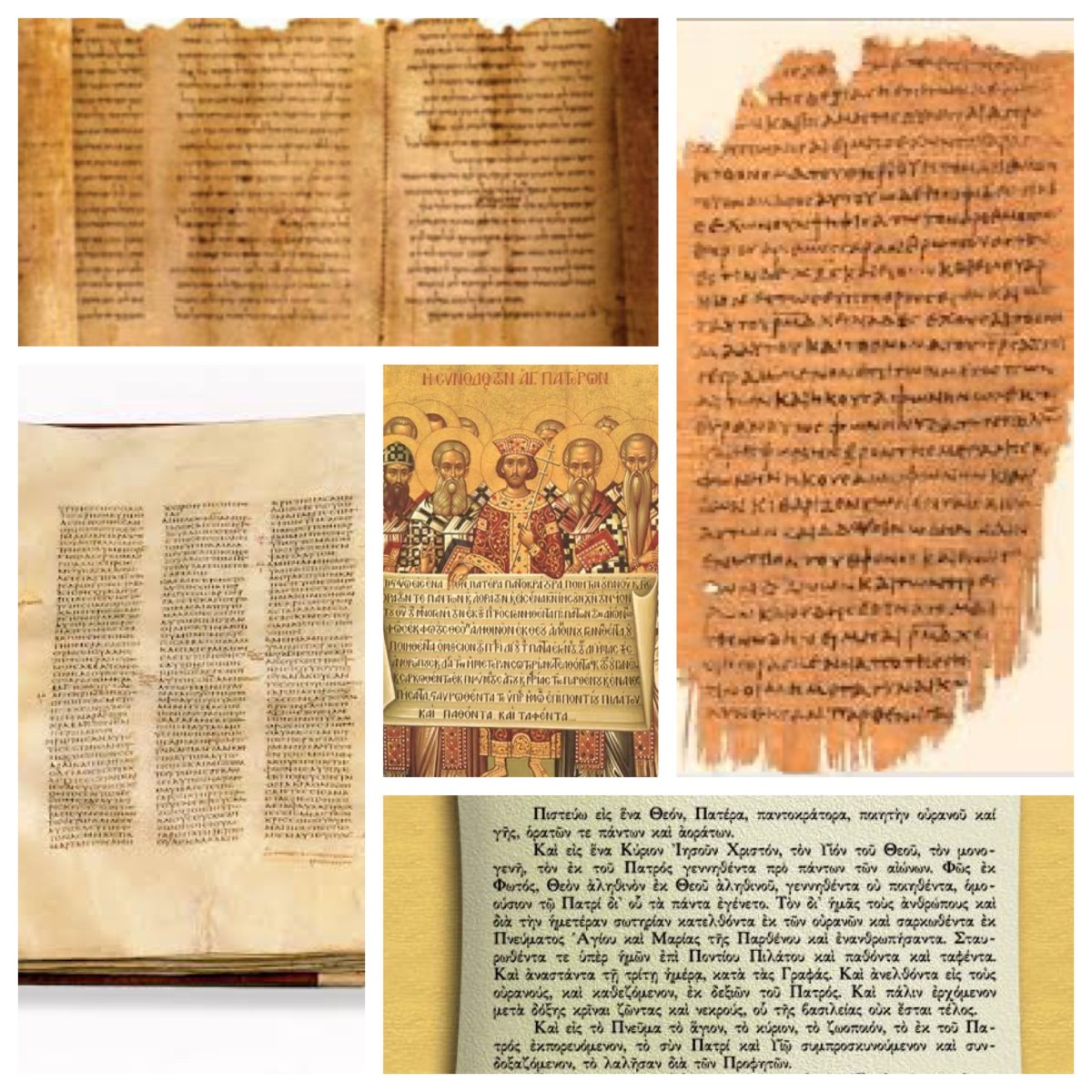

This year, 2025, marks 1700 years since the Council of Nicaea was held. The Council was called by the Roman emperor Constantine; he invited bishops (local church leaders) from around the Roman Empire, to meet in in his imperial palace in Nicaea, Bythinia (in modern-day Turkey). They met in council from May to July in 325CE. The traditional account of the Council was that 318 bishops attended; most came from eastern churches, with only a small number from western churches. Despite this lopsided representation, the council is known as the first of a series of Ecumenical Councils, allegedly representing the worldwide church.

The end result of the Council was a Creed which bears the name of the meeting place: the Nicene Creed. Half a century later, this creed was expanded at the Council of Constantinople in 381 CE—another council called by the Roman emperor, who was by then Theodosius. What came from this council was the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed came to be widely adopted as a foundational expression of the Christian faith. Although various elements in the creed have been interpreted in a variety of ways, it has featured in the ancient churches of the East and the West, and in more recent centuries of the North and South.

However: any mention of the radical life to which Jesus calls disciples is omitted from the two earliest affirmations of faith—the Apostles Creed and the Nicene Creed. In finding a place within the power structures of the Roman Empire, the church fathers left out this aspect of the faith which they confessed. As Chris Budden wrote,

“The teachings of Jesus were a bit of an embarrassment to the [4th century] church and its relationship with power. The creeds which were developed at that time say almost nothing about the real life of Jesus or his teachings. Jesus is a saviour figure rather than one whose life and teachings matter.” (Chris Budden, Why Indigenous Sovereignty Should Matter To Christians, Wayzgoose, 2018, page 62).

The church fathers focussed on “other worldly” matters. Jesus became something of a super man, swooping down from on high to rescue humans from the mess of life and take them to a heavenly home, rather than a prophetic sage active within the gritty realities of earthly life, confronting injustice and living with compassion and grace.

What would a revised Creed look like, if we were to shape one today so that it identified and expressed the essential teachings of Jesus? I have pondered this over the last few years, and have a few suggestions to make.

If we follow the short, staccato precision of the earliest Creed, the Apostles Creed, we could insert something like:

Loving God and loving neighbour,

living in faith and working for justice,

he lived as he taught his followers to live,

praying for the coming of God’s rule here and now.

That’s short and sweet, summing up a lifetime’s teaching in four lines. In my mind, it has the virtue of citing the “two great commandments” that Jesus highlighted, using the key term “justice”, aligning words with deeds, as Jesus exhorted, and focussing on the rule of God, which was the topic for many of the parables and sayings uttered by Jesus.

But this probably fails to do justice to the full range of teachings that are placed on the lips of Jesus in the Gospels (or, at least, in the three Synoptic Gospels).

If we prefer the more expansive developments that unfold in later versions of credal affirmation, we could propose something like:

We rejoice that he came to give

sight for the blind,

mobility for the lame,

acceptance for the outcast,

and good news for the poor.

We remember that he guided us

to turn the other cheek and walk the extra mile,

to lend to those in need, expecting nothing in return,

to do to other people what we would have them do to us.

As we walk the way of Jesus,

who was put to death on a cross,

yet raised back up to life,

we take up our cross,

and lay down our lives;

we seek to love God with all of our being

and to love others as our neighbours.

In Jesus, we can see what the reign of God looks like;

in following him, we proclaim that reign in our lives,

we yearn that justice will mark all that we do,

and we celebrate the gift of life in abundance

as we work together for the common good.

Yes, that is much longer; it tries to pick up various phrases from scripture which might resonate with us today. It touches on a number of the teachings and sayings of Jesus which are valued within the church. A more expansive creed like this might provide a more realistic statement and a more effective teaching resource for the church today, perhaps?

An interesting aspect of this process is that it forces you to make some choices amongst the array of words attributed to Jesus … it forces you to show your hand with regard to your own personal “canon within the canon” or ” red letter verses” in the teaching of Jesus.

You can see what I chose. I wonder what you would choose?

*****

See previous posts at