The passage from the prophet Isaiah which is to be read in worship services (where the Revised Common Lectionary is used) this coming Sunday contains some striking words.

What to me is the multitude of your sacrifices? says the LORD;

I have had enough of burnt offerings of rams and the fat of fed beasts;

I do not delight in the blood of bulls, or of lambs, or of goats.

When you come to appear before me, who asked this from your hand?

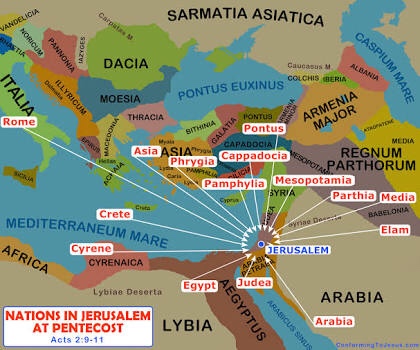

What was required in worship at the time of Isaiah were sacrifices and offerings, the handing over of first fruits, the slaughter of animals, the shedding of blood. These were the essence of the worship being offered in the Temple in Jerusalem by the people of Israel, some eight hundred years before the time of Jesus. This was the way that worship was to take place, in accord with the laws and commandments handed to the people and administered by the priests.

Yet the prophet is clear, that the Lord God has told him: such offerings and sacrifices are, by themselves, inadequate and ineffective.

Trample my courts no more; bringing offerings is futile; incense is an abomination to me. New moon and sabbath and calling of convocation–I cannot endure solemn assemblies with iniquity. Your new moons and your appointed festivals my soul hates; they have become a burden to me, I am weary of bearing them.

And so, in one fell swoop, says Isaiah, it would seem that the Lord God of Israel effects radical change, dismisses centuries of tradition, casts aside beloved and well-rehearsed practices. I am weary of them, says God of all those offerings and sacrifices, all those feasts and festivals, that were integral to Israelite worship.

This oracle of the prophet was obviously an important word from the Lord. It is placed as the first oracle, the first prophetic declaration, right at the start of the book of the prophet Isaiah. The books of the major prophets are arranged thematically, not chronologically. And this oracle is filled with references to the fundamental requirements of the Temple cult. The offerings and sacrifices that he describes were exactly what the priests were charged with administering and overseeing.

We need to read the prophecy of Isaiah alongside the prescriptions for the Temple, set out in detail in Leviticus. Sacrifices and offerings, dedicating the first fruits and sacrificing the best animals as offerings to God—these are what God has commanded and what God requires, according to the book of Leviticus. And these practices did, In fact, continue, for centuries after the time of Isaiah.

Yet Isaiah disputes with the people, and the priests, of Israel, concerning these ritual practices. The rituals of offerings and sacrifices caused God distress. They do not fill the deity with delight. I am weary of them, says God, according to Isaiah. Your incense is an abomination!

And it strikes me a powerfully vivid, that, in the midst of this prophetic word, we encounter a term of deepest criticism, which is also drawn from the priestly language of Leviticus: the word abomination.

*****

The word translated as abomination in our Old Testament is the Hebrew word tōʻēḇā (תֹּועֵבָה). It is a word that appears many times in Hebrew scripture; and the most widely-known usage would be in the two verses in Leviticus which forbid the shaming of one man by another by engaging in forced sexual relationships between the two men (Lev 18:22, 20:13).

These are verses which are regularly quoted today to justify a negative attitude towards homosexual relationships, even though the specific cultural customs and practices of the day were quite different from customs in our own times. The ancient texts seek to prohibit the shaming of one male by another; this is quite different from what we recognise today when we consider long term, faithful, committed relationships between two consenting adults of the same gender.

But these are not the only occurrences of this term abomination. The word features in Proverbs 6:16-19, which lists seven things which are considered by God to be abominations: “haughty eyes, a lying tongue, hands that shed innocent blood, a heart that devises wicked schemes, feet that are swift in running to mischief, a false witness who utters lies, and one who spreads strife among brothers.”

Tōʻēḇā, abomination, is also used in Hebrew Scriptures (the Christian Old Testament) to refer to idolatry, as well as assorted sexual acts such as prostitution in society, prostitution in the pagan temples of the day, and adultery.

Elsewhere in scripture it is applied to child sacrifice, and to a range of unjust business practices, such as dishonesty in financial transactions, charging excessive interest rates on loans, and using rigged weights in the marketplace.

It describes the practice of oppressing the poor and the needy, as well as stealing, robbery, and violating the dietary prescriptions of ancient Israel. There are many references to abominations in Hebrew Scripture!

All of these matters are regarded by God as abominations. Not just the matter of sexual relationships between adults of the same gender. And not just the burning of incense in the daily ritual at the Jerusalem Temple.

*****

So this is no light accusation that Isaiah levels against the people of his day. This is a heavy charge: bringing offerings is futile, and incense is an abomination to me is a full-blooded criticism of the temple cult as it was being carried out in the heyday of ancient Israelite society. Incense was integral to the Temple cult.

(You can read the full prescriptions for the daily offering of incense in Exodus 30; and there are about 100 further references to incense throughout the Old Testament.)

So the prophet speaks out against what is taking place in the temple, the holy site on the top of Mount Zion, where the Lord God of Israel was believed to reside, the place to which all offerings and sacrifices were to be brought, to whom incense was offered each day.

And we need to remember, when we encounter the word abomination in our reading of scripture, that it is not just sex—and not just worship—that is in view when this term appears. It is the wholesale abandonment of the ethical requirements which are integral to the Law which God have to the people of Israel.

Not only incense, or offerings, or sabbath ceremonies, or sacrifices of animals, are what offends God; it is the injustice, the lack of compassion, the structural oppression which is what is evil in the sight of the Lord. And certainly, not only sexual relationships; rather, what God yearns for is integrity and honesty, a commitment to compassion and a zeal for justice, in all that we do.

On interpreting the Biblical passages relating to sexuality, see

https://johntsquires.com/2018/07/30/marrying-same-gender-people-a-biblical-rationale/

https://johntsquires.com/2019/06/26/human-sexuality-and-the-bible/