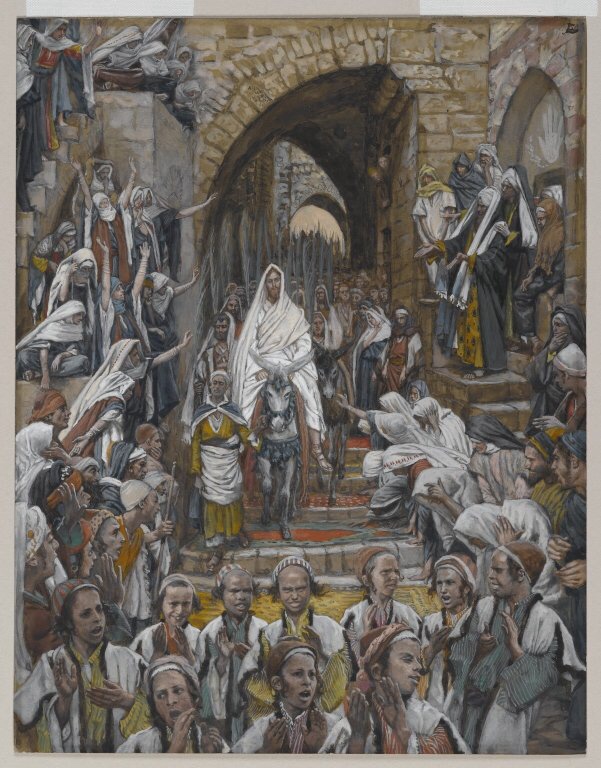

The story of the day that Jesus and his followers drew near to Jerusalem and walked into the city, is a very familiar story. We have, most likely, heard the story, acted out the story, reflected on the story, year after year, at this same time of the year—Palm Sunday. It is a familiar story. (We are Reading it, this year, in the version found in Luke 19.) What do we see in the story? What do we hear in the story?

What do you see? What do you hear? I see pilgrims travelling the winding route to Jerusalem, climbing the hills outside the city as they make their way to the capital of ancient Israel, to the city where the Lord God, so it was believed, was residing in the Holy of Holies, the inner court of the Temple. I hear the noisy, bustling sounds of these pilgrims, excited with anticipation as they make their way along the same routes, up the same hills, year after year, at this time of the year.

It was Passover; one of the three high festivals of the year for good religious Jewish people. It was Passover, the festival of unleavened bread, which recalled the hurried departure of the people, long ago, from captivity in Egypt (Exodus 13). It was Passover, a celebration of the foundational myth at the heart of Jewish identity; the story that tells of the liberating actions of God, in the face of the military might of the Egyptians, the liberation of the people from their time of enforced slavery, as they set out, across the wilderness, to the land they had been promised (Exodus 14–17 and beyond).

Passover. A central religious celebration. But also, a thoroughly politicised procession of pilgrims, wending their way to the holy city, the city of peace. Passover, when bread was eaten without leaven, to signify the haste with which the departure from Egypt took place. Passover, when lambs were roasted and eaten as a sign of that liberation, when bitter herbs were sprinkled eaten as a reminder of the bitterness of slavery. Passover, when the intervention of the divine into the social and political situation of those ancient Israelites was to the fore in the minds of those later pilgrims.

So, we see a scene of pilgrims, a scene of Passover pilgrims, celebrating this ancient political action of God which they hold before themselves as the fundamental paradigm for what their faith means for them. Yes, God is for us! Yes, God will save us!

As the story is told in each of the three synoptic Gospels, Mark, Matthew, and Luke, once the disciples arrive in the city, they seek out lodgings, and at the appointed time, they recline at table to eat the Passover meal, the annual family celebration when the story of that first Passover is told. A time when the actions of God in confronting and overturning the political rulers is remembered, retold, and celebrated.

What do you see? What do you hear? Can you see the Roman soldiers, on the edges, behind the crowds, looking out from the Antonia Fortress? The Roman soldiers, strategically deployed, watching with care the every move that was taking place in the approaches to the city. They knew, from many years’ experience, that the city swelled with the influx of pilgrims each year at this time, as the Passover pilgrims made their way towards Jerusalem. (J.Jeremias, Jerusalem in the time of Jesus, 1966, pp.58–84)

They knew, from years of monitoring the crowds, of the potential for dispute and conflict that simmered underneath the crowds. They knew that this was a high point in the Jewish year, and that any Jew with finely-attuned attention to the history of their people, would know of the charged political consequences of this festival. A celebration of God, intervening, overturning the despotic ruler, liberating the faithful people. As it was long ago in Egypt … so it now could well be, in Jerusalem under Roman rule. A political celebration, wrapped around with religious significance, a celebration of political victory. (E.P.Sanders, Judaism: Practice and Belief, 1992, pp.132–138).

What do you see? What do you hear? Can you see the figure of Jesus, surrounded by his followers, approaching the city? Jesus, seated on the colt, riding on a donkey, the centre of attention, at least for his own followers. An unusual mode of transport, at least! Those in the crowd who knew their scriptures, would have immediately recognised the allusion. The account of this story that we find in Matthew’s Gospel actually specifies the verse that interprets the significance of the donkey.

In Zechariah 9:9, the vision is clear: “your king comes to you, triumphant and victorious, humble and riding on a donkey”. That is what the prophet declares; in this story of Passover pilgrims, Jesus can be seen to be bringing that vision to fruition. And that vision declares that this coming ruler “shall command peace to the nations, and his dominion will be from sea to sea, from the river to the ends of the earth”. That is the vision that Jesus evokes as he rides into Jerusalem on this donkey.

What do you see? What do you hear? Can you hear the cries of the crowd: “Hosanna, hosanna!” they cry. What were they calling out? Hosanna is a foreign term, a word from the Hebrew language, not a common word in our English usage. The best way to translate Hosanna, is “save us”. It is a cry for salvation; a yearning for deliverance. The word appears in the Psalm we have heard today, in Psalm 118:25, where they people cry out, “save us, we beseech you, O Lord!” Save us, redeem us, liberate us.

Psalm 118 was one of the Hallel Psalms, the Praise Psalms, which were associated with celebrations on each of the three great festival days—the Feast of Tabernacles, or Booths; the Feast of Weeks, or Pentecost; and the Feast of Passover. These psalms of praise became particularly associated with the celebrations of the rebuilding of the Temple—an inherently political action, since it was the foreign invasion of Palestine by the Hellenistic Seleucids some two centuries before Jesus which had led to the destruction of the Temple, and it was the political activity of the Jewish Maccabees which had led to the reclaiming of the Temple two decades later.

“Praise you, O God, for we have our Temple, rebuilt, restored, renewed”. So the prayer might well have gone. And it was the political activity of the Maccabees which had brought this about. The Hallel Psalms had become Psalms of Praise for liberating political activity. And this is what the people were singing out!

What do you see? What do you hear? Can you see the people, waving branches of palms? This, too, was an activity intimately associated with the actions of the Maccabees, who were men from a priestly family who took up arms to fight back the Seleucid overlords and reclaim the Temple. The waving of palm branches became closely associated with this event; we can read the instructions in one of the Jewish books (2 Maccabees 10), which directs the people to “carry ivy-wreathed wands and beautiful branches and fronds of palms, and offer hymns of thanksgiving to [God] who had given success to the purifying of their own holy place”.

What do you see? What do you hear? Do you see the cloaks, spread on the ground, by those along the side of the road? A curious detail. What can this mean? Perhaps the more astute of the Jews along the side of the road, would have had some insight; perhaps they recalled the story of the time when a young prophet from Ramoth-gilead declared that God was anointing Jehu, the son of Jehoshaphat, as the next king of Israel.

The story is recounted in 2 Kings 9, and it contains this striking detail, as the prophet decreed, “Thus says the Lord, ‘I anoint you king over Israel’”, and so they took their cloaks and spread them for him on the bare steps, and blew the trumpet, and proclaimed, ‘Jehu is King’” (2 Kings 9:13). Can you hear the resonances in the story of the Passover pilgrims? The cloaks on the steps, when Jehu is King … the cloaks on the wayside, when Jesus comes as King.

What do you see? What do you hear? “Blessed is the coming king, the one who comes in the name of the Lord, the one bringing the peace of heaven into this city here on earth”. So the people cry, singing words from Psalm 118 about the king who comes to implement the kingdom willed by God, and echoing the song of the angels from early in Luke’s Gospel, declaring that, in Jesus, God is bringing “peace on earth, among those whom he favours” (Luke 2:14)

What do you see? What do you hear? Can you see the thoroughly political nature of the activity of Jesus? Can you hear the thoroughly political nature of the cries of the crowd? Hosanna—Save us! Blessed is the King—not Caesar, not ruler of the Romans, but Jesus, King of the Jews, the one Chosen by God to proclaim the kingdom. Can you hear these cries?

In this story of the Passover pilgrims, the cries of the crowd, the actions of the people, the anticipation of the Roman soldiers and the symbolic statement made by Jesus as he rides into the city on a donkey—all of this points to the inherently political, thoroughly this-worldly orientation of the ministry of Jesus. The kingdom is coming, the future kingdom is here and now in our midst, and the kingdom will overturn the expectations and practices of the political powers within this world. The Romans did well to notice, and anticipate, and respond to such a message.

Next Friday, on Good Friday, we will remember that Jesus, ultimately, was condemned to death with a sign that declared that he was “the King of the Jews” (John 19:19–20). The inscription nailed to the cross clearly set out the political nature of the message of Jesus. From the perspective of the Roman rulers, articulated by Pilate, Jesus was given a drastic political punishment for the political insurgency that he was seen as undertaking. That is the one whom we follow. This is the path that he calls us to walk.

What do you see? What do you hear? Our wilderness journey leads us to the city, but requires of us that we take a stand against the city. Jesus stood against Roman imperial power; as he submitted to its might, he showed that there was another way. A way of faithfulness to God’s calling. A way that truly leads to peace, to peace with justice.

For a creative dramatic response to this scene, see https://ruralreverend.blogspot.com/2019/04/palm-sunday-ps-1181-2-19-29-luke-1928.html