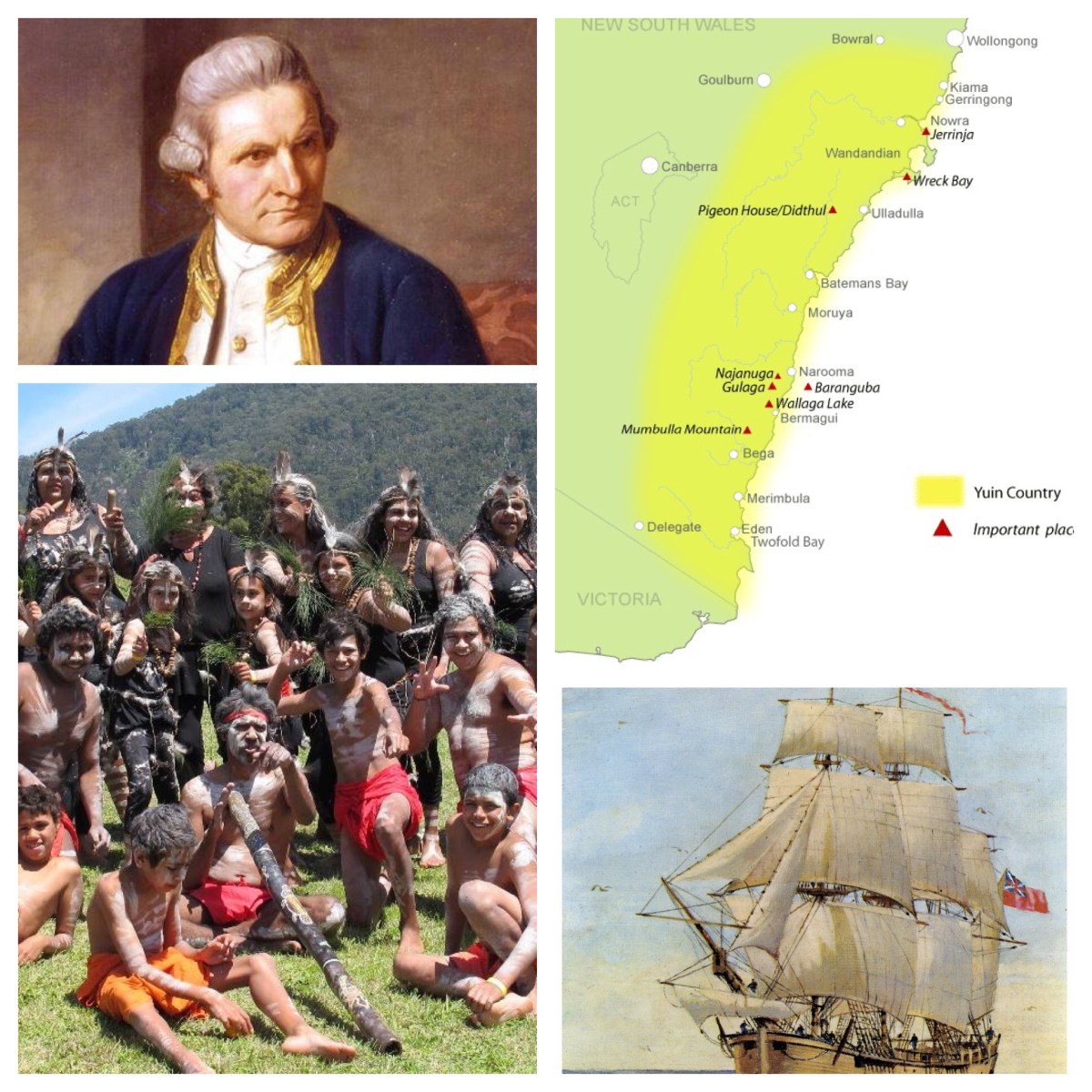

It was 250 years ago today (Sunday 29 April 1770) that British sailor, Isaac Smith, set foot on the east coast of the continent that we know now as Australia. Smith was a sailor on board the ship HMS Endeavour, captained by Lieutenant James Cook, which was on a tour around the globe to explore the seas for what was presumed to be Terra Australis Incognita, the “unknown southern land”. It is said that Cook ordered him, “Jump out, Isaac”, as the boat came in close to shore in the large bay into which they had navigated.

Isaac Smith was not the first European person to setting foot on Australia soil—that honour goes to Dutch navigator, Willem Janszoon, in 1606, on what was was the first of 29 Dutch voyages to Australia in the 17th century. Nor was Smith the first Englishman to touch Australian soil—William Dampier had landed on the peninsula north of Broome that now bears his name, on his trip in 1688. But Smith’s captain, James Cook, and the others on his ship HMS Endeavour, play a dominant role in our Australian historical awareness.

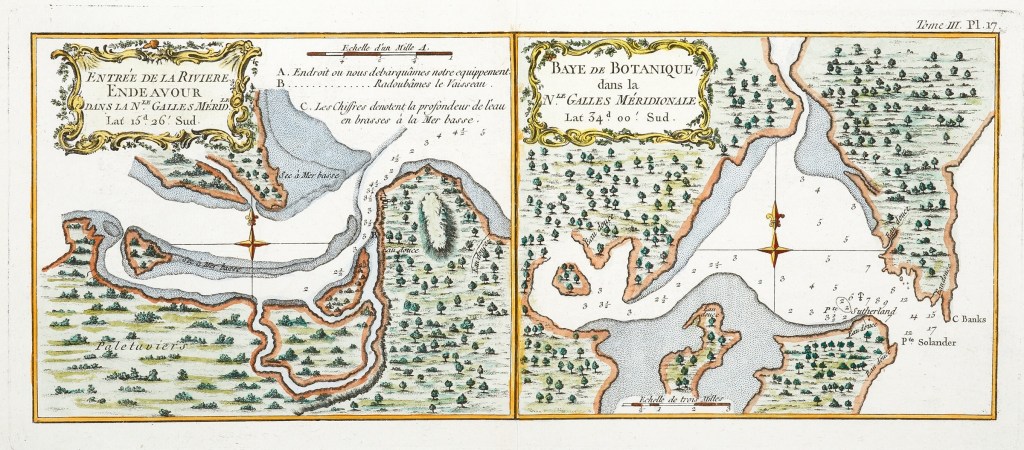

HMS Endeavour had launched in 1764 as the Earl of Pembroke, to work as a collier, transporting coal. The Navy purchased her in 1768 for Cook’s scientific mission to the Pacific Ocean. Cook was in charge of an expedition which included observing the transit of Venus across the sun in 1769, circumnavigating both islands of New Zealand, and then mapping the eastern coastline of Australia, laying claim to the whole continent at the place he named Possession Island, before heading home via Batavia (now Jakarta) and the Cape of Good Hope (South Africa).

Cook and his men followed Smith onto land, setting foot that day on the beach now known as Silver Beach, in the bay which Cook initially called Stingrays Harbour. His log for 6 May 1770 records: “The great quantity of these sort of fish found in this place occasioned my giving it the name of Stingrays Harbour”.

However, in the journal prepared later from his log, Cook wrote instead: “The great quantity of plants Mr. Banks and Dr. Solander found in this place occasioned my giving it the name of Botanist Botany Bay”. [In the transcriptions from his journal, words which lines through them have been crossed out by Cook and others put in their place. It’s a rough piece of work.]

Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander were two of the three scientists who traveled on the Endeavour (the other was Herman Spöring), along with two artists and four of Banks’ servants. The scientists were to undertake scientific investigations at each place visited, the artists were to record the vistas encountered. The servants, of course, were to attend to the daily needs of these gentlemen.

Cape Solander Lookout (near modern-day Kurnell on the southern head of Botany Bay) and Cape Banks (the northern headland at the entry to Botany Bay) recall their roles in that expedition. And various Sydney suburbs also commemorate Joseph Banks: Banksia, Bankstown and Banksmeadow. Spöring has a statue honouring him in Sydney (although no location is named after him.) We have not forgotten these scientists.

James Cook, of course, is well-commemorated, both in eastern Australia (Cook’s River and James Cook Boys’ Technology High School in NSW, the suburb of Cook in the ACT, James Cook University and Cooktown in Queensland) as well as internationally (the Cook Islands, the Cook Strait which separates the two islands of Aotearoa New Zealand, and the Cook Inlet in Alaska—Cook visited there in 1778). He even has a whole dedicated Wikipedia page listing all the ways his name is remembered! (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_places_named_after_Captain_James_Cook)

And what of Isaac Smith? With a surname like that, the possibility of being remembered in such commemorations is low. Smith was apparently a cousin of Cook’s wife, Elizabeth. He sailed on two of the three expeditions that Cook undertook to the South Sea Islands, as they were then called. And he was promoted to captain of the frigate HMS Perseverance, before retiring (and being promoted to the supernumerary position of Rear Admiral).

In his retirement, Smith shared a house for some time with Cook’s widow, his cousin, Elizabeth. It appears that he never married. In his will he had instructed that a sum of £700 was to be left to the church of St Mary the Virgin in Merton, the interest from which was to support the poor of the parish. A memorial to Smith, originally financed by Elizabeth Cook, stands in the church grounds. His assistance to the poor is testimony enough to his life.

(I found this information also on Wikipedia, at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isaac_Smith_(Royal_Navy_officer))

*****

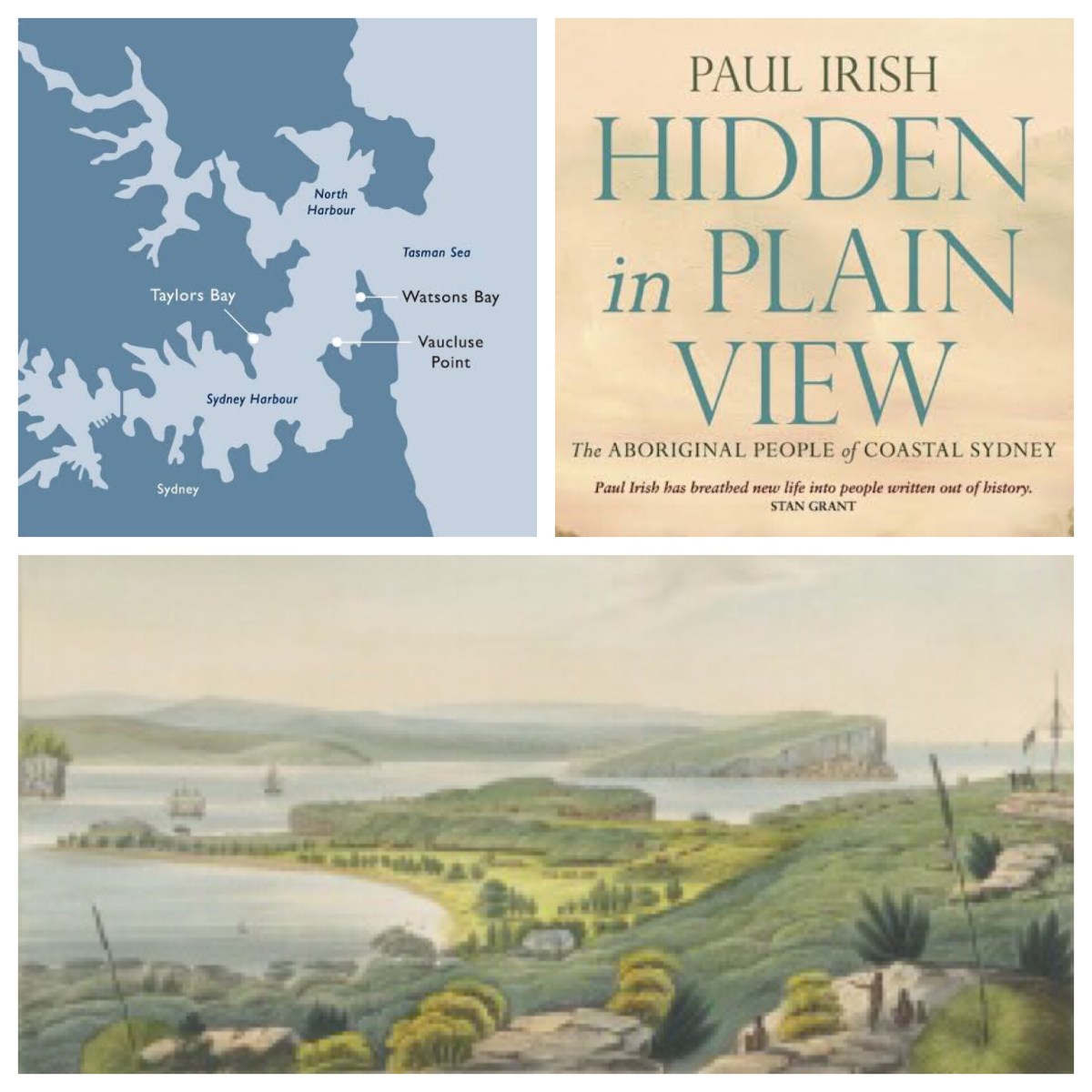

But for me, the larger question relates to the ways in which we remember (or obliterate) the people who had already lived for millennia on the land on which Smith, Banks, Solander, Cook, and others set foot on, just 250 years ago. The land adjacent to Botany Bay was settled for many thousands of years by the Tharawal and Eora people, and the various clan groups within those nations.

What names did they use to describe this bay? Some suggest it may have been Ka-may. By what names did they refer to the south and north headlands of this bay? I have seen indications of Bunnabi for the north head. And Kurnell itself could have been known as Bunna Bunna.

(See the Australian Museum’s “Place names chart” at https://australianmuseum.net.au/learn/cultures/atsi-collection/sydney/place-names-chart/)

Just a few days before setting foot on Terra Australis, on 23 April, Cook had made his first recorded direct observation of indigenous Australia. When they were near Bush Island off Bawley Point (halfway between the townships now known as Bateman’s Bay and Ulladulla), Cook had written in his journal, “[we] were so near the Shore as to distinguish several people upon the Sea beach they appear’d to be of a very dark or black Colour but whether this was the real colour of their skins or the C[l]othes they might have on I know not.”

It is striking that the first observation made by a white man about the indigenous people relates to the colour of their skin. That colour difference has fuelled so much tension, aggression, misunderstanding, fear, and hatred, and, sadly, caused far too many deaths.

Archaeological evidence from the shores of Botany Bay has yielded evidence of indigenous settlement which can be dated to 5,000 years ago. But the stories of the people reach back countless millennia; the stories they tell are timeless. Evidence from other parts of the continent points to indigenous occupation for 40,000, 60,000, even 75,000 years or more.

During the days that his ship was moored in Ka-may (Botany Bay), Cook had various interactions with the Eora people and made many observations about them. Again and again, Cook demonstrates the essence of the colonial mindset; inevitably, he judged what he saw entirely in terms of the customs and practices of Georgian England.

On 28 April, Cook recounted as follows: “At this time we saw several people a shore four of whome where carrying a small boat or Canoe which we imagined they were going to but into the water in order to come off to us but in this we were mistaken.”

So Cook set out with Banks and Solander, and Tupaia, a Polynesian man whom Banks had convinced to come with them on this journey as a navigator. Cook had met Tupaia in July 1769, on the island of Ra’iatea, in the group we know today as the Society Islands. Sadly, Tupaia would later die en route to England, in December 1770 from a shipborne illness contracted when Endeavour was docked in Batavia. The ship was being repaired in order to be fit the return journey to England.

Cook’s journal continues, “we put off in the yawl and pull’d in for the land to a place where we saw four or five of the natives who took to the woods as we approachd the Shore which disapointed us in our the expectation we had of getting a near view of them if not to speak to them but our disapointment was heighten’d when we found that we no where could effect a landing by reason of the great surff which beat every where upon the shore.”

The aborted attempt to make landfall was not in vain, however, as Cook then writes, “we saw hauld up upon the beach 3 or 4 small Canoes which to us appear’d not much unlike the small ones of New Zeland, in the woods were several trees of the Palm kind and no under wood and this was all we were able to observe of the country from the boat after which we returnd to the Ship about 5 in the evening.”

On the day they eventually made landfall, at the place he dubbed Stingrays Bay, Sunday 29 April, Cook provided further observations: “Sunday 29th In the PM winds southerly and clear weather with which we stood into the bay and Anchor’d under the South shore about 2 Mile within the entrence in 6 fathoms water, the south point bearing SE and the north point East. Saw as we came in on both points of the bay Several of the natives and a few hutts.”

Contact was then made: “[We saw] men women and children on the south shore abreast of the Ship to which place I went in the boats in hopes of speaking with them accompaned by Mr Banks Dr Solander and Tupia – as we approached the shore they all made off except two Men who seem’d resolved to oppose our landing – as soon as I saw this I orderd the boats to lay upon their oars in order to speake to them but this was to little purpose for neither us nor Tupia could understand one word they said.”

He continues, “we then threw them some nails beeds & came ashore which they took up and seem’d not ill pleased with in so much that I thout that they beckon’d to us to come ashore but in this we were mistaken for as soon as we put the boat in they again came to oppose us upon which I fired a musket between the two which had no other effect than to make them retire back where bundles of thier darts lay and one of them took up a stone and threw at us which caused my fireing a second Musquet load with small shott and altho’ some of the shott struck the man yet it had no other effect than to make him lay hold of a Shield or target to defend himself.”

Thus was set the pattern for multiple engagements between the British and the indigenous peoples—engagements usually marked by suspicion, and always skewed by the superior power held by the British, with their muskets.

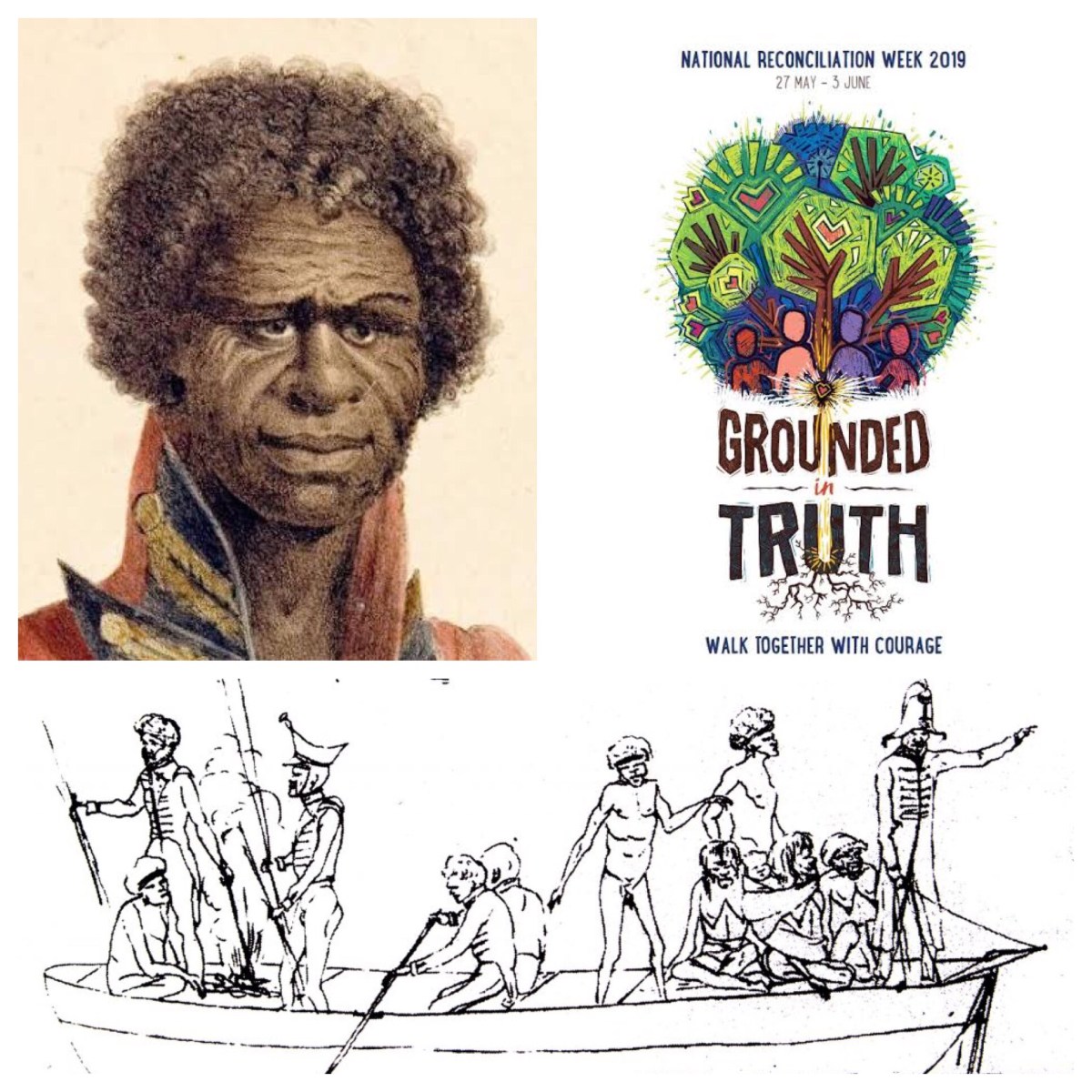

of Cook’s landing and initial contact with the Indigenous people.

The conflicted nature of the relationship is evident

from this imaginative reconstruction,

no doubt shaped by the century of relationships

that stood in between the event and the artwork.

And then, Cook described their response to the musket fire: “emmediatly [sic] after this we landed which we had no sooner done than they throw’d two darts at us this obliged me to fire a third shott soon after which they both made off, but not in such haste but what we might have taken one, but Mr Banks being of opinion that the darts were poisoned made me cautious how I advanced into the woods.”

There would be no genial getting to know each other, no opportunity for cautious enquiry and polite interaction. Suspicion, and judgemental assessment, was in play from the start. The pattern set from this encounter, in the assessment made by Banks and the musket shots fired at the indigenous people by Cook’s soldiers, was a tragic dynamic which would play out again and again, for centuries to come.

Cook continues, “We found here a few Small hutts made of the bark of trees in one of which were four or five small children with whome we left some strings of beeds etc a quantity of darts lay about the hutts these we took away with us – three Canoes lay upon the bea[c]h the worst I think I ever saw they were about 10 12 or 14 feet long made of one peice of the bark of a tree drawn or tied up at each end and the middle kept open by means of peices of sticks by way of Thwarts.”

“The worst I think I ever saw”. Objective description and subjective evaluation and criticism were mixed together; Cook, like many others after him, was unable simply to look, listen, and learn about what was valued for the indigenous peoples. He had to assess in terms of his own criteria and his own perspective, here, and always.

The colonial mindset always saw its own worldview as the norm, and others patterns as inadequate. And what he saw this day, he believed, fell short of his standards—even if it had served the indigenous people perfectly well for thousands and thousands of years.

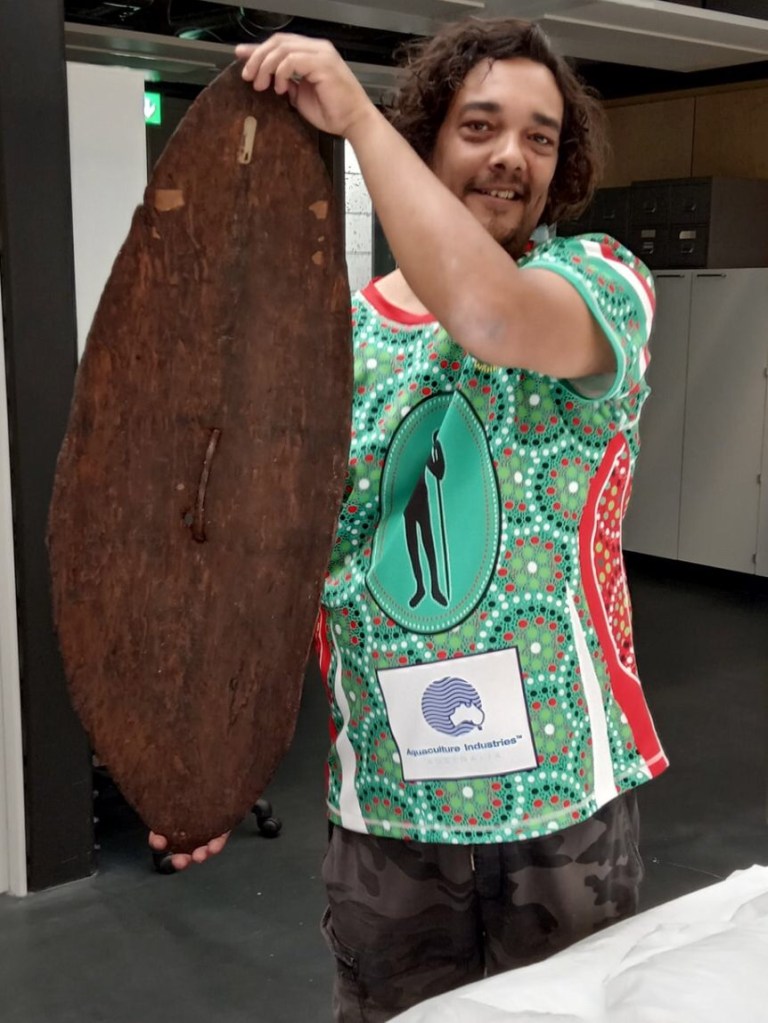

As a curious postscript to this part of the voyage, those days at Ka-may (Botany Bay) are remembered in another way. An artefact collected during Cook’s time here in 1770 is the bark shield of the local indigenous peoples, now known as the Gweagal Shield. It is a rare instance of such an item.

from the south coast of New South Wales,

holds the Gweagal Shield

at the British Museum

in London.

The shield is currently (and controversially) held by the British Museum; that itself perpetuates the inherent colonial element, as the British laid claim to the shield and simply took it from those who had valued and utilised it. See https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-05-11/british-museum-battle-for-stolen-indigenous-gweagal-shield/11085534

For more thoughts on indigenous history, see my previous blogs at:

On the Day of Mourning, https://johntsquires.wordpress.com/2019/01/16/the-profound-effect-of-invasion-and-colonisations/

On Arthur Philip, https://johntsquires.wordpress.com/2019/01/18/endeavour-by-every-possible-means-to-conciliate-their-affections/

On James Cook, https://johntsquires.wordpress.com/2019/01/20/we-never-saw-one-inch-of-cultivated-land-in-the-whole-country/

On William Dampier, https://johntsquires.wordpress.com/2019/01/22/they-stood-like-statues-without-motion-but-grinnd-like-so-many-monkies/

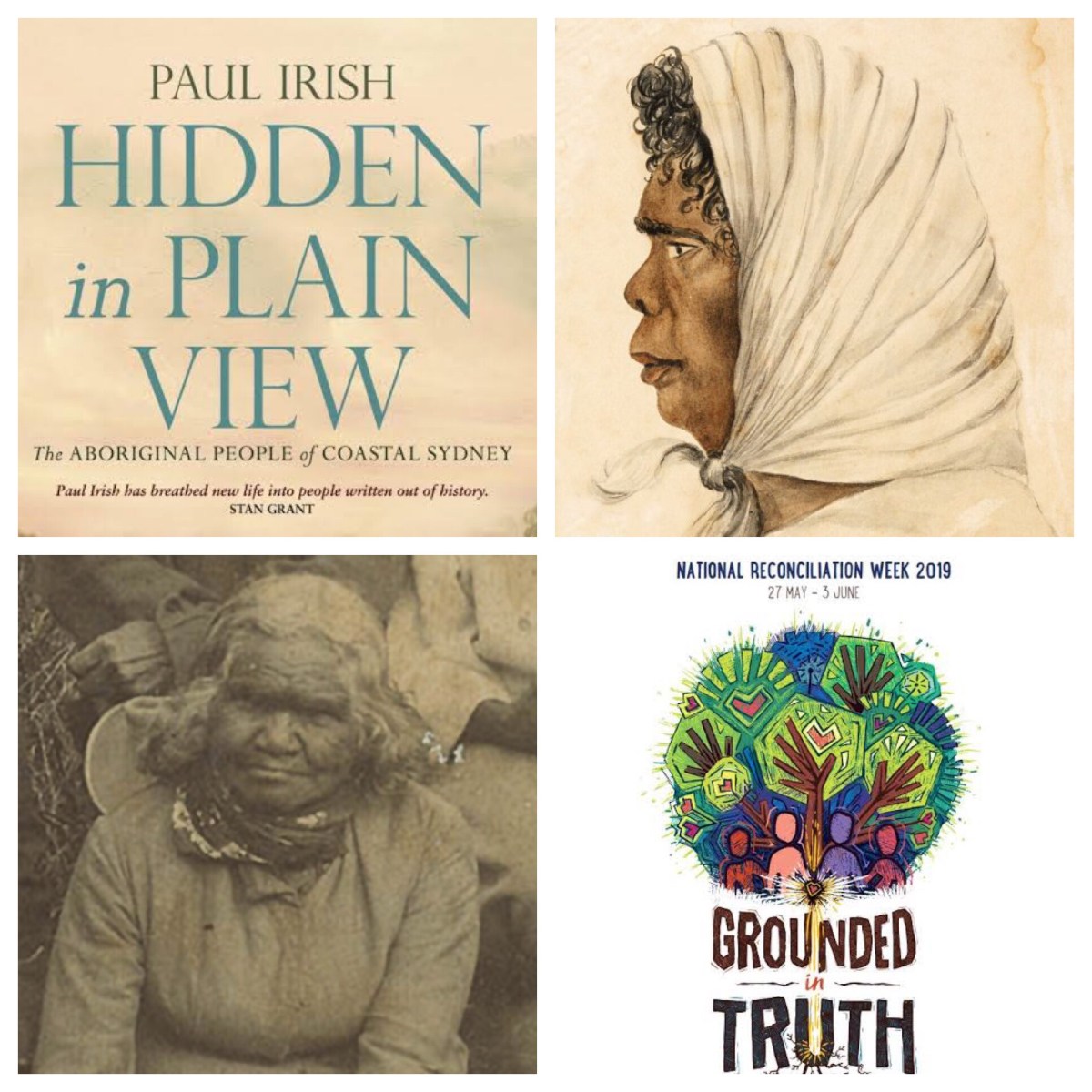

On recent books, https://johntsquires.wordpress.com/2019/01/24/resembling-the-park-lands-of-a-gentlemans-residence-in-england/

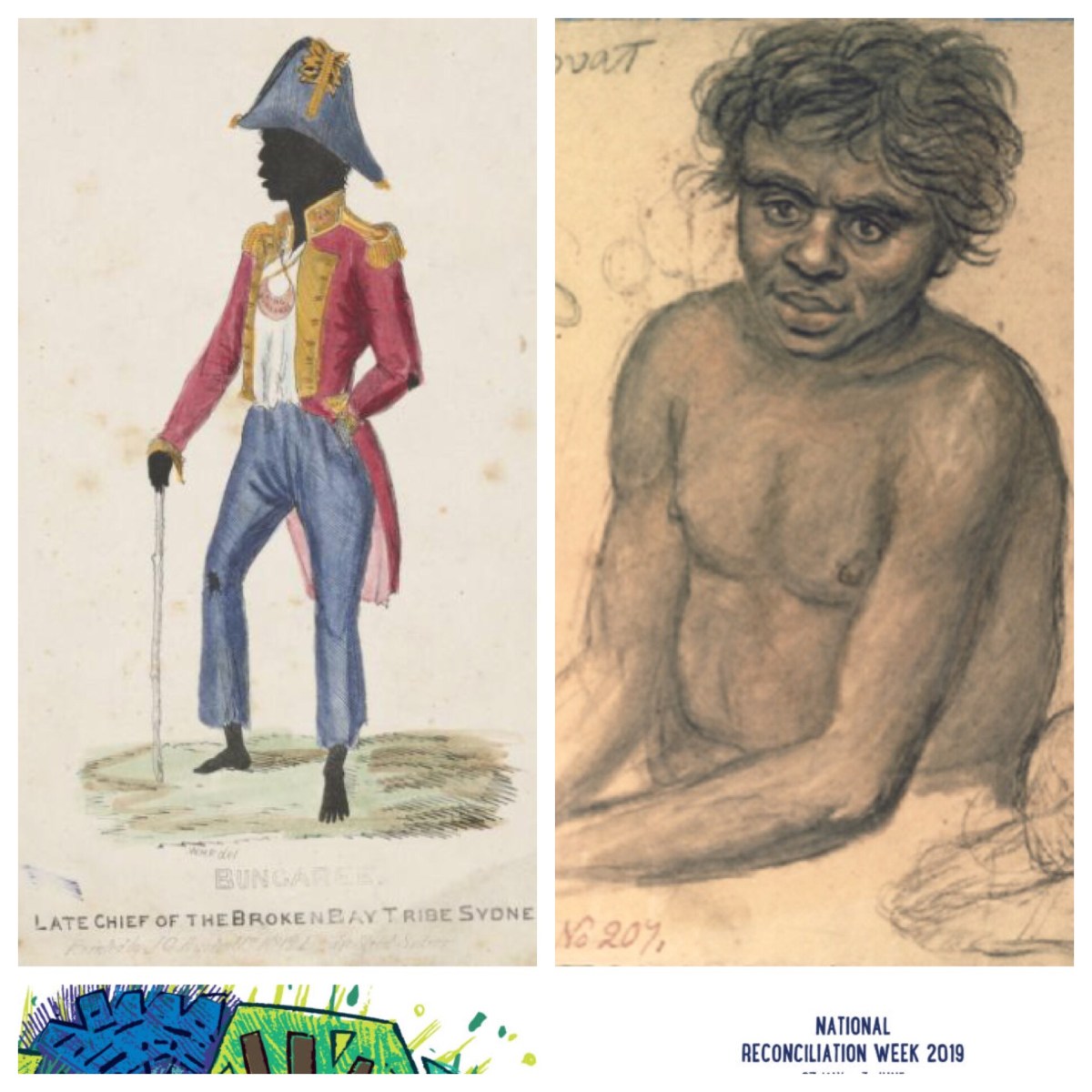

On Cook and Flinders, https://johntsquires.com/2019/01/25/on-remembering-cook-and-flinders-and-trim-bungaree-and-yemmerrawanne/

On Cook and the Yuin people, https://johntsquires.com/2020/04/23/they-appeard-to-be-of-a-very-dark-or-black-colour-cook-hms-endeavour-and-the-yuin-people-and-country/