The Gospel reading for this coming Sunday (Mark 13:1–8) offers an excerpt from longer speech, a block of teaching which Jesus delivered to his disciples (13:3–37), some time after they had arrived in the city of Jerusalem (11:1–11). It’s a striking speech, with vivid language and dramatic imagery. As Jesus’ last long speech in this Gospel, it certainly makes a mark!

The speech is delivered beside the towering Temple, built under Solomon, rebuilt under Nehemiah (13:1, 3). That temple was a striking symbol for the people of Israel—it represented their heritage, their traditions, their culture. The Temple was the place where the Lord God dwelt, in the Holy of Holies; where priests received sacrifices, designed to enable God to atone for sins, and offerings, intended to express the people’s gratitude to God; where musicians led the people in singing of psalms and songs that exulted God, that petitioned God for help, that sought divine benevolence for the faithful covenant people

Or so the story goes; so the scriptures said; so the priests proclaimed. The holiest place in the land that was holy, set apart and dedicated to God. Yet what does Jesus say about this magnificent construction? “Not one stone will be left here upon another; all will be thrown down” (13:2). Jesus envisages the destruction of the Temple. Not only this; he locates that destruction within the context of widespread turmoil and disruption: “nation will rise against nation, and kingdom against kingdom; there will be earthquakes in various places; there will be famines” (13:8). And then, to seal this all, Jesus refers directly to the fact that “the end is still to come” (13:7).

The End. Eight centuries before Jesus, the prophet Amos had declared, “the LORD said to me, ‘the end has come upon my people Israel; I will never again pass them by’” (Amos 8:2). Amos continues, declaring that God has decreed that “on that day … I will make the sun go down at noon, and darken the earth in broad daylight. I will turn your feasts into mourning, and all your songs into lamentation; I will bring sackcloth on all loins, and baldness on every head; I will make it like the mourning for an only son, and the end of it like a bitter day” (Amos 8:9–10).

That image of The Day when the Lord enacts justice and brings punishment upon the earth, because of the evil being committed by people on the earth, enters into the vocabulary of prophet after prophet. Amos himself declares that it is “darkness, not light; as if someone fled from a lion, and was met by a bear; or went into the house and rested a hand against the wall, and was bitten by a snake. Is not the day of the LORD darkness, not light, and gloom with no brightness in it?” (Amos 5:18–20).

Isaiah, just a few decades after Amos, joined his voice: “the Lord of hosts has a day against all that is proud and lofty, against all that is lifted up and high … the haughtiness of people shall be humbled, and the pride of everyone shall be brought low; and the Lord alone will be exalted on that day” (Isa 2:12, 17). He warns the people, “Wail, for the day of the Lord is near; it will come like destruction from the Almighty!” (Isa 13:6).

Isaiah uses a potent image to describe this day: “pangs and agony will seize them; they will be in anguish like a woman in labour” (Isa 13:7). He continues, “the day of the Lord comes, cruel, with wrath and fierce anger, to make the earth a desolation, and to destroy its sinners from it” (Isa 13:8), and later he portrays that day as “a day of vengeance” (Isa 34:8).

Zephaniah, who was active at the time when Josiah was king (640–609 BCE) declares that “the day of the Lord is at hand; the Lord has prepared a sacrifice, he has consecrated his guests” (Zeph 1:7); “the great day of the Lord is near, near and hastening fast; the sound of the day of the Lord is bitter, the warrior cries aloud there; that day will be a day of wrath, a day of distress and anguish, a day of ruin and devastation, a day of darkness and gloom, a day of clouds and thick darkness ” (Zeph 1:14–15).

Habakkuk, active in the years just before the Babylonian invasion of 587 BCE, declares that “there is still a vision for the appointed time; it speaks of the end, and does not lie” (Hab 2:3); it is a vision of “human bloodshed and violence to the earth, to cities and all who live in them” (Hab 2:17).

Later, during the Exile, Jeremiah foresees that “disaster is spreading from nation to nation, and a great tempest is stirring from the farthest parts of the earth!” (Jer 35:32); he can see only that “those slain by the Lord on that day shall extend from one end of the earth to the other. They shall not be lamented, or gathered, or buried; they shall become dung on the surface of the ground” (Jer 35:33). He also depicts this day as “the day of the Lord God of hosts, a day of retribution, to gain vindication from his foes” (Jer 46:10).

And still later (most likely after the Exile), the prophet Joel paints a grisly picture of that day: “the day of the Lord is coming, it is near—a day of darkness and gloom, a day of clouds and thick darkness! Like blackness spread upon the mountains, a great and powerful army comes; their like has never been from of old, nor will be again after them in ages to come. Fire devours in front of them, and behind them a flame burns. Before them the land is like the garden of Eden, but after them a desolate wilderness, and nothing escapes them.” (Joel 2:1-3).

Later in the same oracle, he describes the time when the Lord will “show portents in the heavens and on the earth, blood and fire and columns of smoke; the sun shall be turned to darkness, and the moon to blood, before the great and terrible day of the Lord comes” (Joel 2:30–31). Joel also asserts that “the day of the Lord is near in the valley of decision; the sun and the moon are darkened, and the stars withdraw their shining” (Joel 3:14–15).

*****

The language of The Day is translated, however, into references to The End, in some later prophetic works. In the sixth century BCE, the priest-prophet Ezekiel, writing in exile in Babylon, spoke about the end that was coming: “An end! The end has come upon the four corners of the land. Now the end is upon you, I will let loose my anger upon you; I will judge you according to your ways, I will punish you for all your abominations.” (Ezek 7:2–3).

And again, Ezekiel declares, “Disaster after disaster! See, it comes. An end has come, the end has come. It has awakened against you; see, it comes! Your doom has come to you, O inhabitant of the land. The time has come, the day is near—of tumult, not of reveling on the mountains. Soon now I will pour out my wrath upon you; I will spend my anger against you. I will judge you according to your ways, and punish you for all your abominations.” (Ezek 7:5–8). This day, he insists, will be “a day of clouds, a time of doom for the nations” (Ezek 30:3; the damage to be done to Egypt is described many details that follow in the remainder of this chapter).

Obadiah refers to “the day of the Lord” (Ob 1:15), while Malachi asserts that “the day is coming, burning like an oven, when all the arrogant and all evildoers will be stubble; the day that comes shall burn them up, says the Lord of hosts, so that it will leave them neither root nor branch” (Mal 4:1).

Malachi ends his prophecy with God’s promise that “I will send you the prophet Elijah before the great and terrible day of the Lord comes; he will turn the hearts of parents to their children and the hearts of children to their parents, so that I will not come and strike the land with a curse” (Mal 4:5–6). This particular word is the final verse in the Old Testament as it appears in the order of books in the Christian scriptures; it provides a natural hinge for turning, then, to the story of John the baptiser, reminiscent of Elijah, who prepares the way for the coming of Jesus, evocative of Moses.

Another prophet, Daniel, declares that “there is a God in heaven who reveals mysteries, and he has disclosed to King Nebuchadnezzar what will happen at the end of days” (Dan 2:28), namely, that “the God of heaven will set up a kingdom that shall never be destroyed, nor shall this kingdom be left to another people. It shall crush all these kingdoms and bring them to an end, and it shall stand forever” (Dan 2:44).

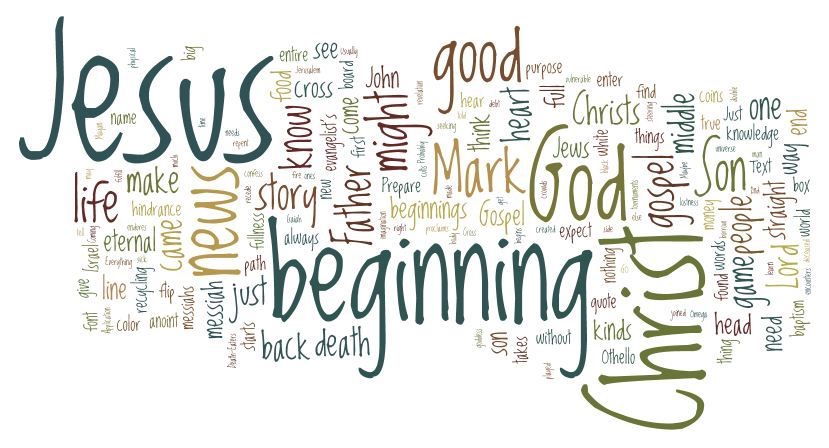

Whilst the story of Daniel is set in the time of exile in Babylon—the same time as when Ezekiel was active—there is clear evidence that the story as we have it was shaped and written at a much later period, in the 2nd century BCE; the rhetoric of revenge is directed squarely at the actions of Antiochus IV Epiphanes, who had invaded and taken control of Israel and begun to persecute the Jews from the year 175BCE onwards.

The angel Gabriel subsequently interprets another vision to Daniel, “what will take place later in the period of wrath; for it refers to the appointed time of the end” (Dan 8:19), when “at the end of their rule, when the transgressions have reached their full measure, a king of bold countenance shall arise, skilled in intrigue. He shall grow strong in power, shall cause fearful destruction, and shall succeed in what he does. He shall destroy the powerful and the people of the holy ones.” (Dan 8:23–24). This seems to be a clear reference to Antiochus IV.

Antiochus IV Epiphanes, the king of the Seleucid Empire (r. 175-164 BCE),

desecrating the Temple in Jerusalem.

Still later in his book, Daniel sees a further vision, of seventy weeks (9:20–27), culminating in the time of “the end” (9:26). In turn, this vision is itself spelled out in great detail in yet another vision (11:1–39), with particular regard given to the catastrophes taking place at “the time of the end” (11:1–12:13; see especially 11:25, 40; 12:4, 6, 9, 13).

This final vision makes it clear that there will be “a time of anguish, such as has never occurred since nations first came into existence” (12:1), when “evil shall increase” (12:3) and “the wicked shall continue to act wickedly” (12:10). The visions appear to lift beyond the immediate context of the Seleucid oppression, and paint a picture of an “end of times” still to come, after yet worse tribulations have occurred.

***

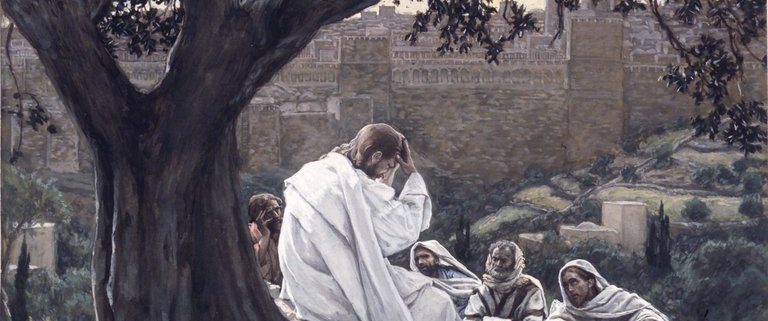

Could these visions of “the end” be what Jesus was referring to, as he sat with his followers on the Mount of Olives, opposite the towering Temple? Later in the same discussion with his disciples, he indicates that “in those days, after that suffering, the sun will be darkened, and the moon will not give its light, and the stars will be falling from heaven, and the powers in the heavens will be shaken” (Mark 13:24). This picks up the language we have noted consistently throughout the prophetic declarations, in Amos, Joel, Isaiah, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Ezekiel, and Daniel.

The judgement of God, says Jesus, with the “gathering up the elect from the four words, from the ends of the earth to the ends of heaven” (13:27), will be executed by “the Son of Man coming in clouds with great power and glory” (13:25)—language which draws directly from the vision of Daniel concerning “one like the Son of Man, coming with the clouds of heaven” (Dan 7:13).

So the resonances are strong, the allusions are clear. Jesus is invoking the prophetic visions of The Day, The End; the judgement of God, falling upon the wicked of the earth. And he deliberately applies these vivid and fearsome prophetic and apocalyptic traditions to what he says about the Temple. By linking his teaching directly to the question of four of his disciples, Peter, James, John, and Andrew (Mark 13:3), enquiring about the Temple, Jesus appears to be locating the end of the Temple—its sacrifices and offerings, its psalms and rituals, its wealth and glory … and perhaps also its priestly class—in the midst of the terrible, violent retributive judgements of the Lord God during the days of the end.

The language also resonates with the end section of 2 Esdras, in which God informs “my elect ones” that “the days of tribulation are at hand, but I will deliver you from them”. Those who fear God will prevail, whilst “those who are choked by their sins and overwhelmed by their iniquities” are compared with “a field choked with underbrush and its path overwhelmed with thorns” and condemned “to be consumed by fire” (2 Esdras 16:74–78). (This book claims to be words of Ezra, the scribe and priest who was prominent in the return to Jerusalem in the 5th century BCE, but scholarly opinion is that it was written after the Gospels, perhaps well into the 2nd century CE.)

All of the happenings that are described by Jesus in his teachings whilst seated with his followers outside the Temple (Mark 13:3) can be encapsulated in this potent image: “this is but the beginning of the birth pangs” (13:8). This is imagery which reaches right back to the foundational mythology of Israel, which tells of the pains of childbirth (Gen 3:16). It is language used by prophets (Jer 4:3; 22:23; 49:2; 49:24; Hos 13:13; Isa 21:3; 66:7–8; Micah 4:9; 5:3).

This chapter in Mark’s Gospel, along with the parallel accounts in Luke (chapter 21) and Matthew (chapter 24), are regarded as instances of apocalyptic material. The meaning of apocalyptic is straightforward: it refers to the “unveiling” or “revealing” of information about the end time, the heavenly realm, the actions of God.

Such a focus does not come as a surprise to the careful reader, or hearer, of this Gospel. This style of teaching is consistent with, and explanatory of, the message which the Gospels identify as being the centre of the message proclaimed by Jesus: “The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God has come near; repent, and believe in the good news” (Mark 1:14); “repent, for the kingdom of heaven has come near” (Matt 4:17); “I must proclaim the good news of the kingdom of God to the other cities also; for I was sent for this purpose” (Luke 4:43). Each of these distillations of the message is apocalyptic—revealing the workings of God as the way is prepared for the coming of the sovereign rule of God.

Apocalyptic is the essential nature of Jesus’ teachings about “the kingdom of God”. This final speech confirms the thoroughly apocalyptic character of Jesus’ teaching. The parables he tells about that kingdom are apocalyptic, presenting a vision of the promised future that is in view. The call to repent is apocalyptic, in the tradition of the prophets. The demand to live in a way that exemplifies righteous-justice stands firmly in the line of the prophetic call. Such repentance and righteous-just living is as demanding and difficult as giving birth can be.

Mark’s Gospel has drawn to a climax with the same focussed attention to the vision of God’s kingdom, as was expressed at the start. The beginnings of the birth pangs are pointers to the kingdom that Jesus has always had in view. Jesus was, indeed, a prophet of apocalyptic intensity.

Of course, that still leaves the basic interpretive question: how do we make sense of this apocalyptic fervour in today’s world??? So to grapple with that, there’s more posts coming …..

*****

See also https://johntsquires.com/2020/11/24/towards-the-coming-the-first-sunday-in-advent-mark-13/

https://johntsquires.com/2020/11/04/discipleship-in-an-apocalyptic-framework-matt-23-25/