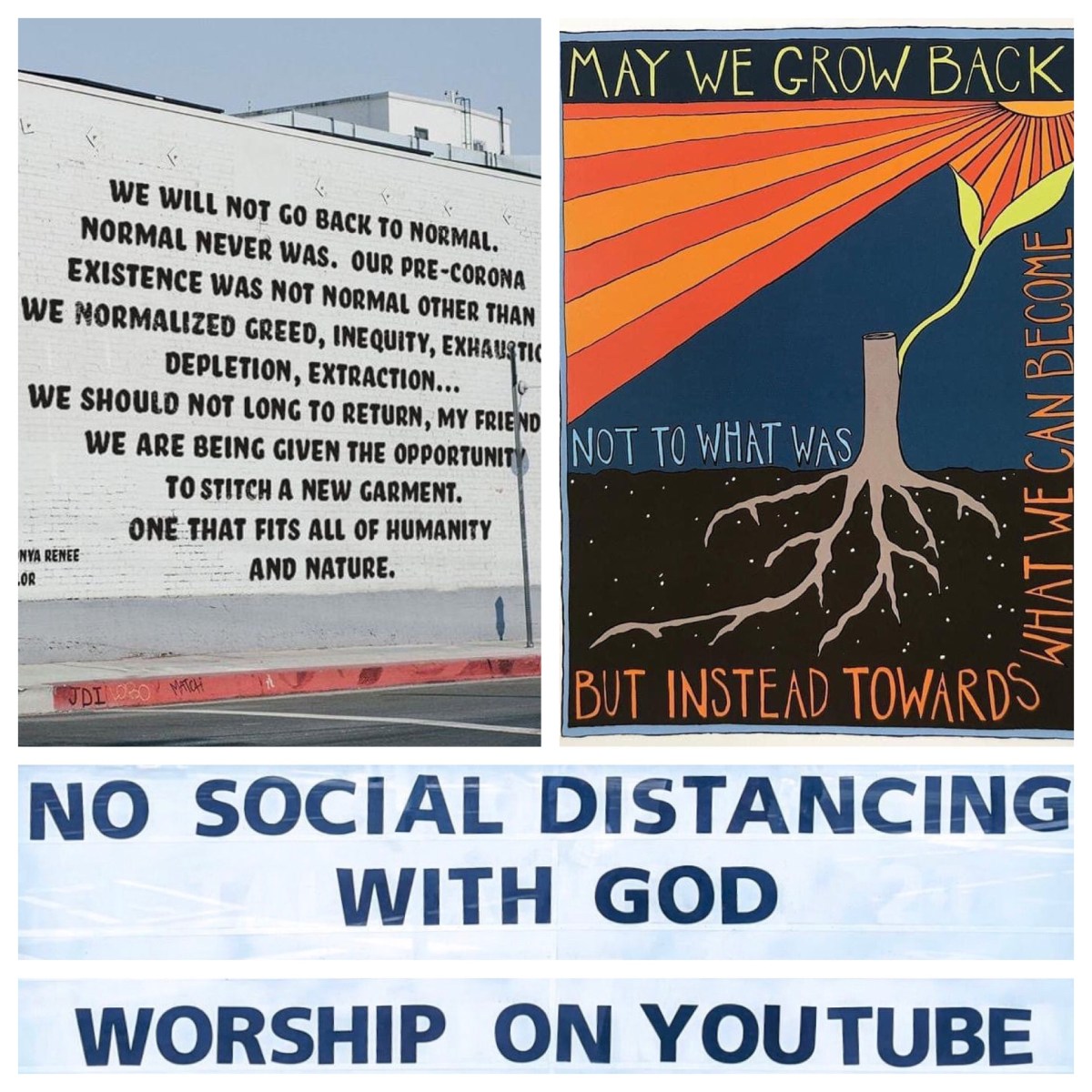

Change is happening around us. We are noticing changes taking place in society. The COVID-19 virus has forced a range of changes on us. Decades ago, Bob Dylan penned a folk song, “The times, they are a-changin’”, which has come to be seen as an anthem celebrating the changes that are always taking place in our society.

But in the present time, as we live under significant restrictions on gathering in person, as we keep our distance and stay at home for all manner of things, we sense that our times, are, indeed, a-changin’. So let’s ponder those changes.

Some of these are not good changes. Some may well be beneficial changes. We have had to let go of some valued ways of operating. We have also had to learn new skills and adopt new practices. This is what happens during a time of transition: many things can change. How we deal with these changes is important. What we choose to accept, and what we chose to reject, is up to us.

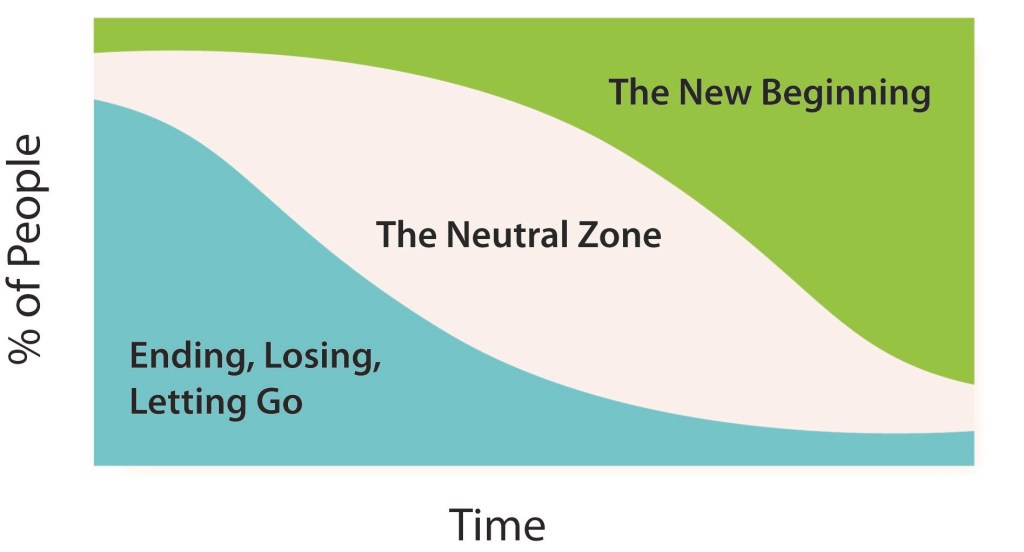

William Bridges has written an insightful book about such processes, entitled Managing Transitions (2009). Bridges talks about transitions in terms of three stages (as the graphic indicates): first, there is the letting go; then there is the neutral zone of being in-between; and finally, the connection into a new place, a new way of being.

In that neutral, in-between zone, there is a need for us to develop a capacity to live within the discomfort of ambiguity which arises during the experience of loss, as we move away from the familiar. That is the space we are in now, in the midst of restrictions on gathering, as we work to slow the spread of the COVID-19 virus. We are experiencing, in various ways, the discomfort of ambiguity, as things shift under our feet.

In that liminal space, that unfamiliar territory, we have the time and space to reconsider, to review, to reshape, to remake ourselves. What changes will we accept? What changes will we reshape? What changes will we reject?

****

Some changes taking place in society feel difficult. Unemployment rates are rising, and many people who move out of employment will find it hard, if not impossible, to gain work after the restrictions end. Funerals are taking place with friends and most family unable to attend; weddings are occurring with even less people physically present. People who live alone are experiencing more intense feelings of loneliness and are craving real human interaction.

People who are vulnerably housed will have far fewer options for shelter at night during winter, as Safe Shelter programs will not be running because of the risks of passing on the virus. The rates of domestic violence are rising, as pressures in the home situation grow, for some, to boiling point. More people are drawing on the social services network provided by our government, but they will hit the ground with a thump after the restrictions end, when benefits will return to their “normal” level (well below the poverty line).

Some small businesses are looking at a glum future, considering the prospect of having to close for good. Tourism companies and travel agencies are particularly impacted, and their reduced business means loss of employment for significant numbers of people. Apparently more than 16,000 new coronavirus-related online domains have been registered since January 2020—many of which are believed to be set up to enable malware and hacking tools to be sold through COVID-19 “discount codes”.

But some changes are good. More than $1 billion has been saved in poker machine losses in the first five weeks of COVID-19 restrictions in Australia, according to the Alliance for Gambling Reform. There have been 25% less call outs of paramedics in the Ambulance Service in the ACT, because “people are not out and about so much, they are taking things very easy.” In the NT, the same decrease has been observed, because “there’s less traffic on the roads, so less motor vehicle accidents.”

Seeds have sold out, as people plant their own vegetables in anticipation of food shortages. Laying pullets are scarce and those for sale are selling at two or three times the normal price, as people look to guarantee their supply of eggs. Backyard gardening is making a comeback!

“We’ve been riding bikes for years, now, and we have never experienced so many people out and about walking and riding bikes on the bike trails!”, a number of our friends have commented. Meanwhile, in my region, there are no electric bikes available for sale at the moment—all stock has been sold out!

Local communities have rallied together in so many places. People are much more attuned to those folks who are shut-ins or who are self isolating because of their medical conditions or age. Phone calls and food drops at the front door have been made on a regular basis, and online coffee and chat groups are springing up to maintain connections amongst friends who cannot see each other in person.

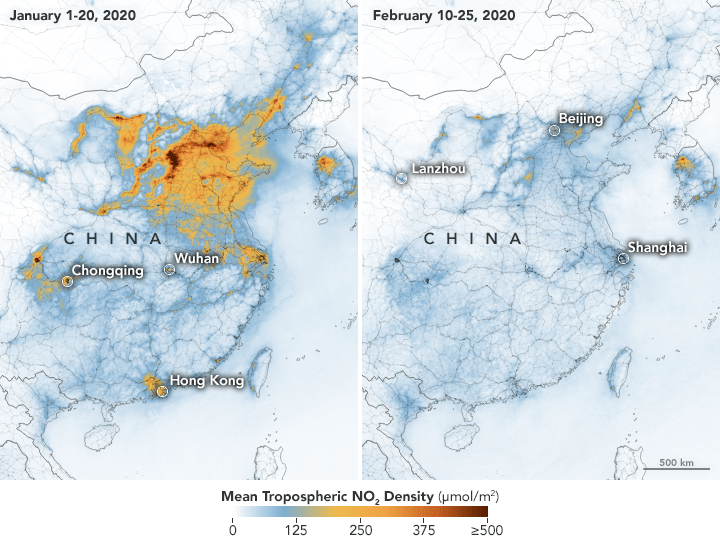

Pollution rates have fallen across the globe at the moment; satellite observations showed that levels of nitrogen dioxide (NO₂) decreased quite significantly over China in the first month that COVID-19 infections were occurring there, February 2020. The same pattern is now taking place in other countries where restrictions on travel, because of the corona virus, means less traffic, less pollution, less NO₂.

(The NO₂ in our air is almost entirely from combustion. When coal and wood burn, nitrogen trapped in the fuel is oxidised as NO₂. Cars and trucks make NO₂ in their engines when they break down nitrogen in the air at extremely high temperatures. It makes a significant contribution to air pollution, which causes acute respiratory issues like asthma, as well as long-term diseases such as stroke, heart disease, and cancer. The World Health Organisation estimates that in recent years, seven million deaths a year have been attributable to air pollution.)

Drug arrests in Chicago have been measured at 42% lower during March, as drug dealers have no choice but to wait out the economic slump. El Salvador reported an average of two killings a day during March, down from a peak of 600 a day a few years ago. Even criminals are practising social distancing, social isolation!

And our Chief Medical Officer is now saying that we need to ensure that some changes in the way we relate to one another remain permanent, and we don’t go back to old ways—he advocates that we keep our distance from each other, continue our good hand hygiene habits, and don’t shake hands with other people. (This will lower the spread of all forms of viral infections, not just COVID-19.)

Changes are happening in society. Which of these beneficial changes will hold fast into the future? Which ones do we really want to hold on to? Which ones do we want to keep, just a little modified, in the future?

*****

We are also noticing changes that are happening in churches. For instance, I have been keeping a collection of comments from people in my home congregation about the positive nature of the changes they are experiencing, such as: “We can see the faces of people at worship with us, instead of the backs of their heads.” “Morning tea was more lively, I got to talk with different people, people that I normally don’t talk with.” “It was easy to go to church, I can sit in my comfortable chair and don’t have to get going early.”

And some more: “We have seen people come to online church who haven’t been able to come to church in person for months.” “We need to keep on offering services by ZOOM for those who can’t get to church in person.” “Finding happiness in the present moment and situation is such a great way to live. Not always easy to pull off, but a great goal.”

A recent conversation I heard between two people was very succinct: “I’m still learning.” “Aren’t we all!” And I have just seen online an elderly man who has never seen the need for a mobile phone, let alone a computer, who got his technologically-literate son to buy him a second-hand laptop, so he could join the Sunday morning worship. He set ZOOM himself and has been participating every week since!

Another ZOOM meeting I attended recently included people from across a number of Congregations who have been in office, in some cases, for quite some time. Someone from one of the places further away from Canberra (where Presbytery staff and most office bearers are based) said, “It’s nice to put a face to a name after all this time”. Another tick for people from dispersed locations meeting together online!

In another Synod-wide online meeting, a comment was made that “the current crisis has brought to a head some long-running issues; we now need to deal with them and get involved in a constructive way”. The situation has stimulated proactive engagement in situations where the tendency had been to hold back and “let’s hope things sorts out by themselves” (which, of course, they rarely, if ever, do!)

I have heard one person comment that they have turned to the Psalms for spiritual nurture, and they observed that, wherever the psalmist reflects desolation, that is almost always followed by a sense of consolation. Perhaps that idea can undergird our prayers and reflections on the current situation.

Another colleague has observed that new, and positive, connections are being made between previously disconnected and distanced communities and individuals, which has been good for the health of the whole body. The challenge of disruption has generated a new pattern of collaboration and hopefulness.

One regional body is taking advantage of this interruption to “business as usual” by focussing on mission planning for the future, asking, “what are we learning in this current disrupted period, that we can apply to being the church in a renewed missional way?”

And many times, now, I have heard a story that runs along the same lines: since we have been in this period of restrictions on gathering, we have been making intentional connections with people who had drifted away from our Sunday gatherings. Now we have refreshed our connections and we are feeling that many of them seem to be “part of us” once again.

Some of the changes are, to be sure, experienced as less than desireable. “How many people are clicking on to online worship more as voyeurs than as fully engaged disciples?”, asked one colleague. Another mused, “my minister seems to be spending all their time playing with technology rather than making contact with people”. These are practices that we need to find a way to balance better.

I’ve heard one person articulate the need to move away from “leading worship well” towards a way to “equip people to grow in their own discipleship”. Some colleagues are devoting significant time, not just to preparing the Sunday worship, but to collating, writing and distributing resources that are available for personal use in the home—reflective worship times, meditations on scripture, studies to deepen discipleship, questions to challenge people to seek new ways of serving in the post-COVID period.

Another church leader has identified the challenges that are immediately before us as we consider how we might serve people with particular issues: people living with disabilities, people dealing with longterm mental illness, people who are vulnerable housed and dependent on church and community provision of safe shelter (especially in winter time). For such people who depend so much on in-person connection, the online manner of connecting leaves much to be desired. (And, for some, they lack any capacity to have the capability of regular, trustworthy online connection.)

By the same token, those whose particular challenge has been that they live at a significant distance from their place of worship, and need to undertake lengthy drives each time they attend worship, fellowship, or church council meetings, have found that being able to attend online, from the comfort of their own home, has many benefits.

So I think that, overall, my take on all of this can be articulated in some short and simple comments: Community is more important than worship. Service is at the centre of the Gospel. Discipleship engages us with the whole of society, not simply the inner club. Consistent relationships with other human beings are crucial. Creativity can flourish when we are thrust into unfamiliar situations. Disruption can deepen our faith, extend our understandings, refresh our mission.

******

Dr Kimberley Norris, an authority on confinement and reintegration at University of Tasmania, has undertaken a detailed study of the mental health of Australians who have overwintered in Antarctica. She found that those who have been through a period of isolation value the experience for what it has taught: They have a better idea of their personal values, and they’re more committed to acting on them. (See https://www.abc.net.au/triplej/programs/hack/coronavirus-covid19-isolation-third-quarter-phenomenon-has-begun/12190270)

The study indicates that the positives from this liminal period can be valued and retained, even as we shed the negatives and less desireable aspects from our time of social,distancing and self isolation.

Dr Norris believes that post-COVID, “we will see differences in the way people engage with each other, in the way people work, in the priorities given to the environment, and the way people think about travel.” And another interesting comment she has: “A lot of people expect spirituality to increase.”

That study clearly indicates that we stand in a critical period of time, during which we have the opportunity to explore our priorities—personal, as disciples, and communal, as a church—and to make commitments to refreshed and innovative ways of operating in the future. It’s an opportunity, not a threat. We ought to rejoice in, and focus on our strengths, not bemoan our situation and become fixated on the weaknesses it has exposed.

So what changes do we want to keep? What things can we change to ensure that the good things that have been happening continue? What new things do we plan to introduce as a result of the changes we have experienced in this period of time? What strategies are we developing to be well placed for the post-COVID situation?

What are your thoughts?

See also https://johntsquires.com/2020/05/04/not-this-year-so-what-about-next-year/