In the Hebrew Scriptures passage that the lectionary sets before us this coming Sunday (in 2 Kings 2), we read about the transition from Elijah the prophet to Elisha the prophet. This is an important moment in the story, as it moves on from the words and deeds of Elijah the Tishbite, later remembered as the great “prophet like fire [whose] word burned like a torch” (Sirach 48:1) and as one who had “great zeal for the law” (1 Macc 2:58).

Whilst Elijah remained in his heavenly abode, it was considered that he would ultimately return from that place “before the great and terrible day of the Lord”; he would come “to turn the hearts of the people of Israel” so that the Lord God “will not come and strike the land with a curse” (Mal 4:5–6). But in the meantime, who would follow him in the earthly realm to declare the word of the Lord and to signal the power of the Lord God by performing miracles, as Elijah had done? This transition story offers the answer.

In the book we know as 1 Kings, the compiler of the Deuteronomic History reports many incidents which attest to the courage and power of Elijah. In his sermon in Nazareth, Jesus refers to the first miracle of Elijah, when he provided a widow in Zarephath with food and oil that “did not fail”, even though the land was in drought (1 Ki 17:1–16). In subsequent incidents in this book, he raises a dead son (17:17–24), confronts King Ahab (18:1–18) and famously stares down the prophets of Baal in a mountaintop showdown (18:19–40), leading to the breaking of the drought (18:41–46).

Elijah later condemns Ahab over his unjust seizure of the vineyard of Naboth (21:17–29) and then stands before Ahab’s son, King Ahaziah, to condemn him to death (2 Ki 1:2–16); a death “according to the words of of the Lord that Elijah had spoken” which is promptly reported (2 Ki 1:17). During the rule of Ahab, Elijah had also most famously heard the Lord God “not in the wind … not in the earthquake … not in the fire”—the standard elements involved in a theophany since the time of Moses (Exod 19:1–6)—but rather in “the sound of sheer silence” (1 Ki 19:11–12). Elijah was his own, distinctive man, with his own, distinctive encounter with God.

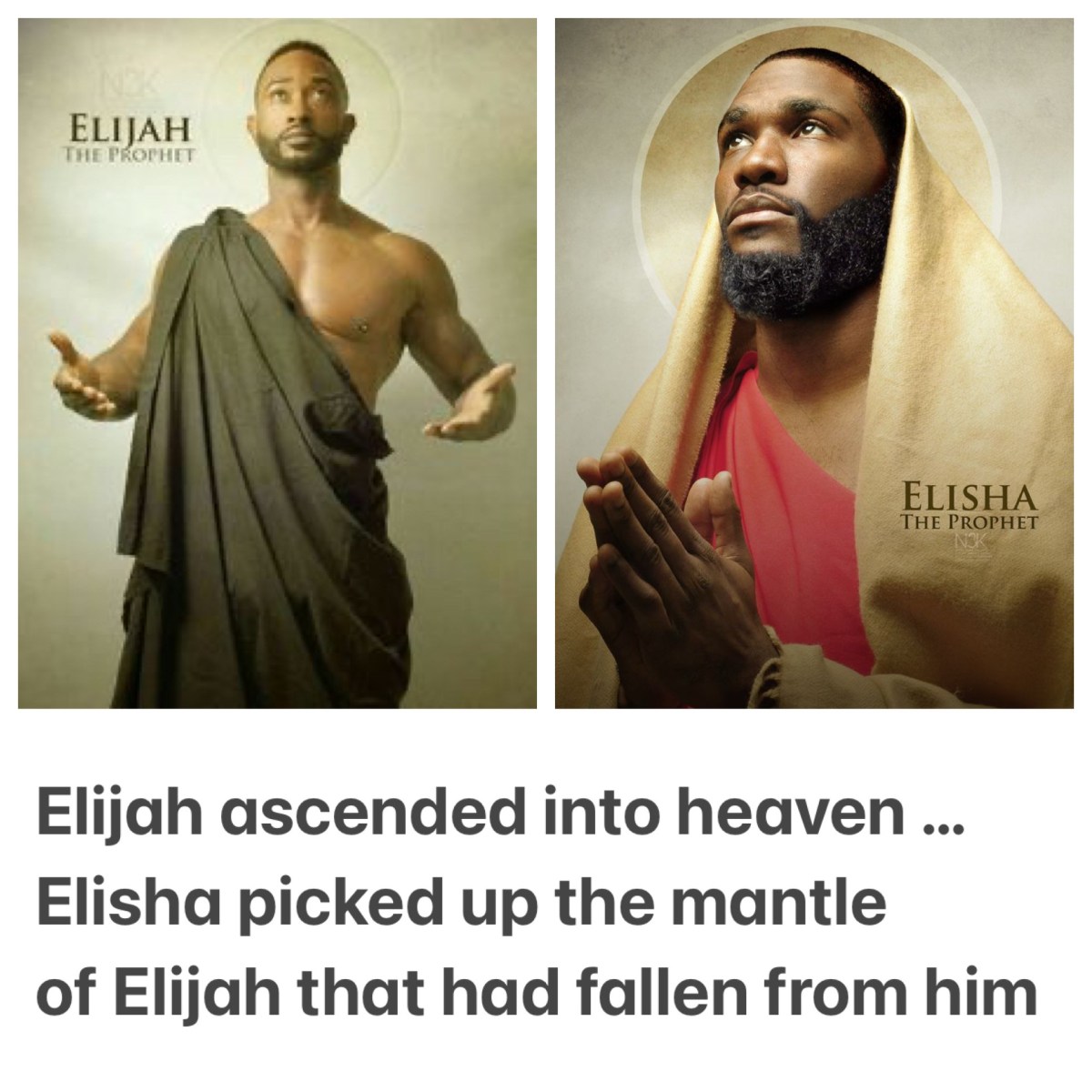

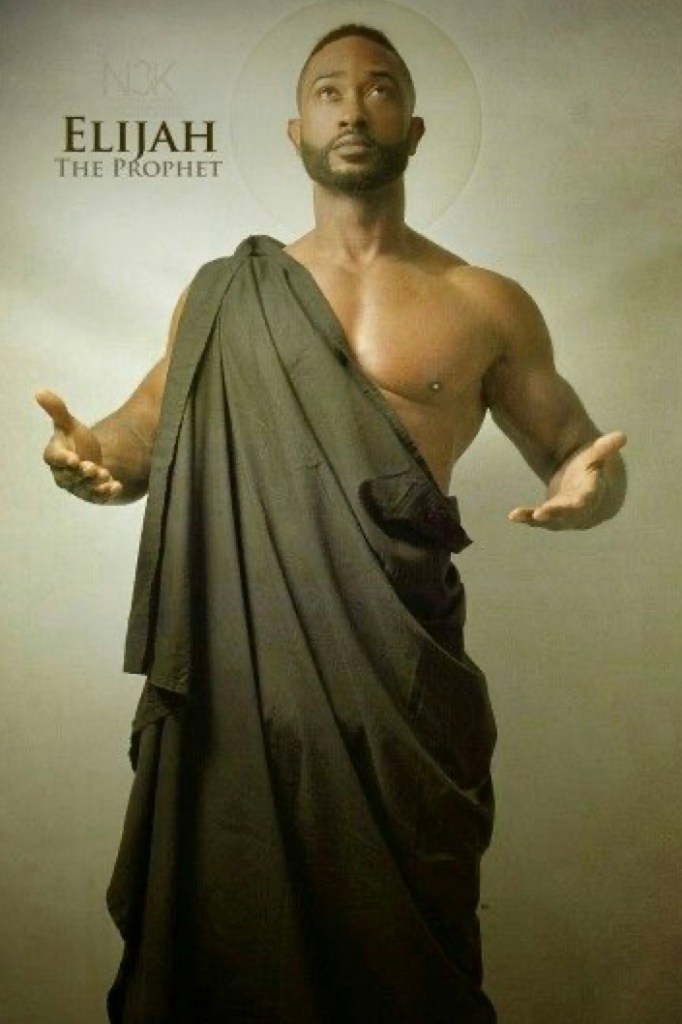

Then, immediately after that encounter, Elijah the Tishbite, from Gilead, called Elisha son of Shaphat, a farmer ploughing his fields, to be his chosen disciple (1 Ki 19:19–21). All of these stories serve as the background to the story that we face on this Sunday’s readings, when Elijah “ascended in a whirlwind into heaven” (2 Ki 2:11) and leaves behind his prophetic mantle, which Elisha then took as his own (2 Ki 2:12–14). From that moment, as “the company of prophets who were at Jericho” declared, “the spirit of Elijah rests on Elisha” (2 Ki 2:13–15).

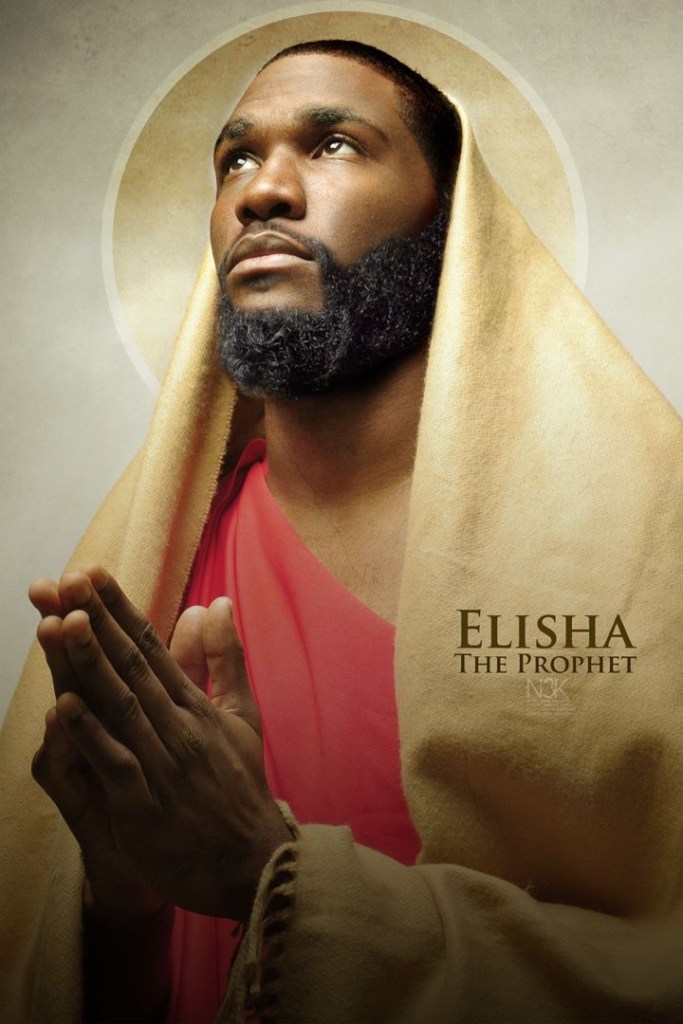

Indeed, Elisha had rather brashly requested of Elijah, “please let me inherit a double share of your spirit” (2:9). Elijah had responded, “you have asked a hard thing; yet, if you see me as I am being taken from you, it will be granted you; if not, it will not” (2:10). Sure enough, as Elisha subsequently watches as “a chariot of fire and horses of fire” take Elijah and he ascends “in a whirlwind” (2:11), Elisha is watching, indeed crying out a description of the spectacle: “father, father! the chariots of Israel and its horsemen!” (2:12). He will surely be doubly blessed. The narrator makes sure we know that Elisha could see Elijah departing, commenting that “when he could no longer see him, he grasped his own clothes and tore them in two pieces” (2:12).

Elisha knows he had the blessing of Elijah when his first action after the departure of his mentor was to pick up the cloak (or mantle) that Elijah had left behind, and immediately uses it to enact a miracle (2:13–14)—replicating what Elijah had just done (2:8). It seems that a distinctive cloak, or mantle, was worn by prophets over the years; although cloaks were common garments—worn, for instance, by Ezra (Ez 9:5) and Job (Job 1:20)—it is thought the cloak or mantle worn by Samuel (1 Sam 15:27) and Elijah (1 Ki 19:13) was a sign of their prophetic role. That certainly seems the case with Elisha (2 Ki 2:8, 12).

Now, Elisha is not exactly my favourite prophet. After all, look at what he did when some small boys taunted him because of his distinctive hairline. They jeered at him, calling him “bald head”; in response, he cursed them and, presumably to enact the curse, “two she-bears came out of the woods and mauled forty-two of the boys” (2 Kings 2:23–24). As a particularly alopecic person myself, this does not particularly endear this prophet to me. Why did his sensitivity about his follicularly-challenged head justify this incredibly excessive response to the games of children?

However, the compiler of the Deuteronomic History sees otherwise. Elisha is honoured as a prophet who is able to perform miracles, who confronts kings, and who declares the word of the Lord forthrightly and without fear. He replicated the last miracle of Elijah (2 Ki 2:8) by striking a steam of water with his newly-acquired mantle, so that “the water was parted to the one side and to the other” (2:13–14). He made good the bad water in Jericho (2:19–22), then spoke the word that made the water flow again in Judah (3:13–20), replicating another miracle of Elijah when he caused an earlier drought in Israel to end (1 Ki 18:41–45).

He later supplies an impecunious widow with an abundance of oil to save her from her debtors (2 Ki 4:1–7) and then raises from the dead the son of a Shunnamite woman (4:8–37). These two miracles replicate actions performed earlier by Elijah (1 Ki 17:8–16, 17–24). Elisha’s miraculous deeds continue as he supplies food to end a famine in Gilgal (2 Ki 4:38–41), feeds a hundred men (4:42–44), and then heals the Syrian army commander Naaman (5:1–19), a story that we will focus on in worship the Sunday after this coming one. And as Elijah had challenged the kings of his day, so Elisha confronts the king of his time (2 Ki 6).

Still more miracles are reported, before Elisha became ill and died (13:14–20). Yet even in death, his miraculous powers continued; the narrative reports that as the Moabites invade the land each spring, “as a man was being buried, a marauding band was seen and the man was thrown into the grave of Elisha; as soon as the man touched the bones of Elisha, he came to life and stood on his feet” (13:21). Whilst Elijah had not died—his ascension into heaven was most certainly while he was still alive (2 Ki 2:11–12)—Elisha had died, but his power to perform miracles lived on (2 Ki 13:21).

In his long “hymn in honour of our ancestors”, Jesus, son of Sirach lavishes praise on Elisha. “When Elijah was enveloped in the whirlwind”, he writes, “Elisha was filled with his spirit. He performed twice as many signs, and marvels with every utterance of his mouth. Never in his lifetime did he tremble before any ruler, nor could anyone intimidate him at all. Nothing was too hard for him, and when he was dead, his body prophesied. In his life he did wonders, and in death his deeds were marvelous.” (Sirach 48:12–14). He was, by all accounts, a worthy successor to Elijah. I may have to allow him that, despite his hyper-sensitivity about his hairstyle.

See also