Elizabeth and I attended the #StopAdani climate crisis rally outside the Federal Parliament this morning. The crowd present was estimated at around 5,000 people. There were people from churches, schoolchildren, union members, as well as members of many community organisations and climate change action groups participating.

Author Richard Flanagan addressed the crowd in his inimitable poetic manner, marking the issues and telling the truth:

“Jabbering ‘jobs, jobs, jobs’ in a hi-vis shirt does not make you a leader”

“The Franklin was more than a river. Adani is more than a mine.”

“Was there hope with the Franklin!? Yes, there was. Is there hope with Adani? Yes, there is!”

Two young female school-age climate strikers stirred the crowd with pointed rhetoric and a call to action. “Change is never implemented by the oppressors. Change must always be demanded by the oppressed.”

Other speakers from various organisations urged the large crowd to hold fast, stand firm, and work for change. “We are on the right side of history. We will Stop Adani.”

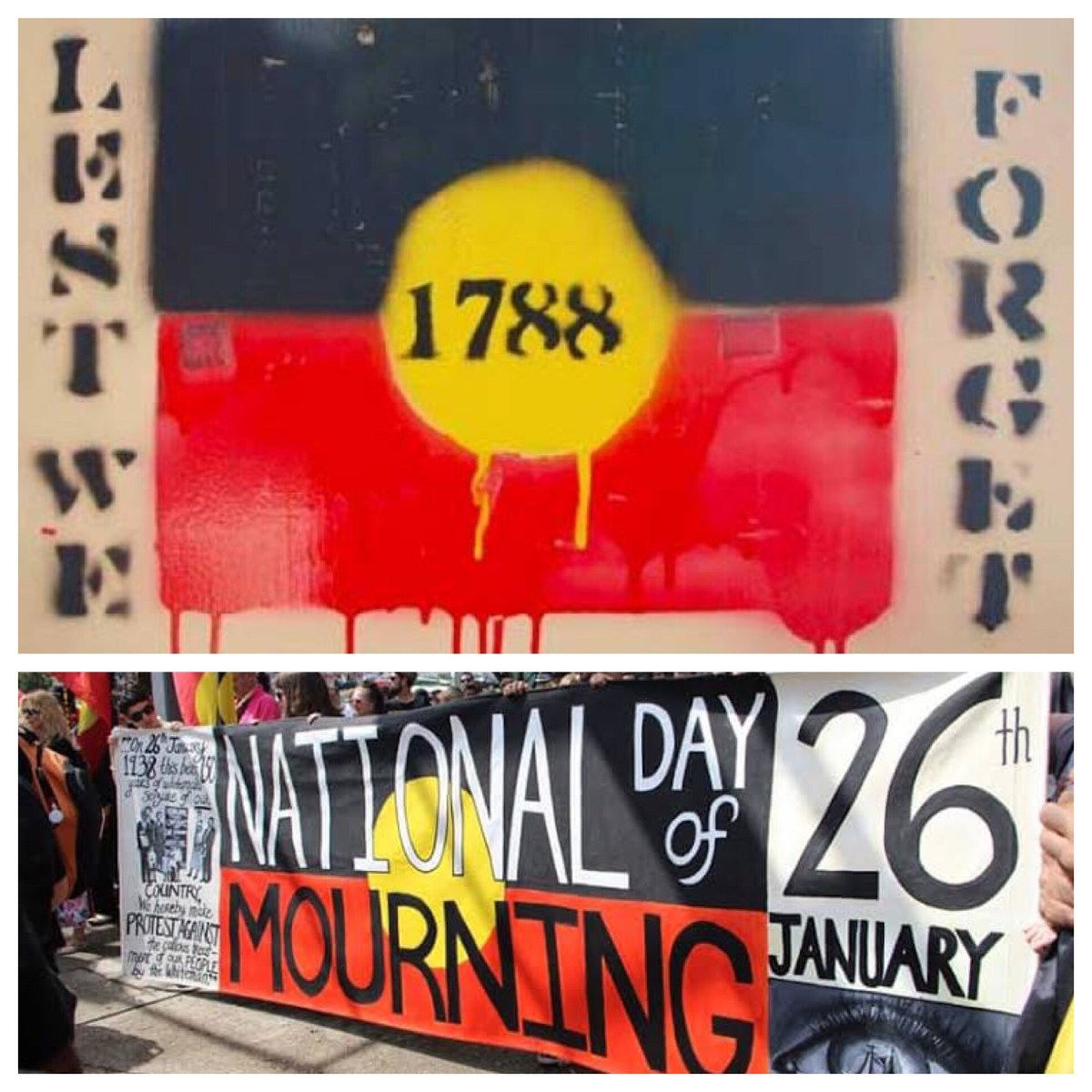

Adrian Burragubba, an elder of the Wangan and Jagalingou people of the Galilee Basin in central western Queensland, reminded the crowd that Adani does not have the consent of the First People of the area, whose ancestral lands, waters and culture would be destroyed by the mime if it went ahead.

Paul Kelly sang two song, including “My island home”, and then Bob Brown brought the rally to a climax with his clarion call: “There will be no divine intervention. The onus is on us. And we will take it.” He noted that there was “a bigger crowd here today, than Bill Shorten will have in Brisbane, than Scott Morrison will have, whenever he has his campaign launch.” Popular opinion is clearly against the development of this mine.

Why is it important to protest against this mine, and to petition our leaders to ensure that the Adani mine and associated works do not go ahead?

The Great Barrier Reef. The mine will see ships travelling through this unique World Heritage Area each year, risking ship groundings, coal and oil spills; and it requires further dredging within the World Heritage Area causing water contamination, destruction of dugong habitat, impacts on Green and Flatback turtle nests, and more.

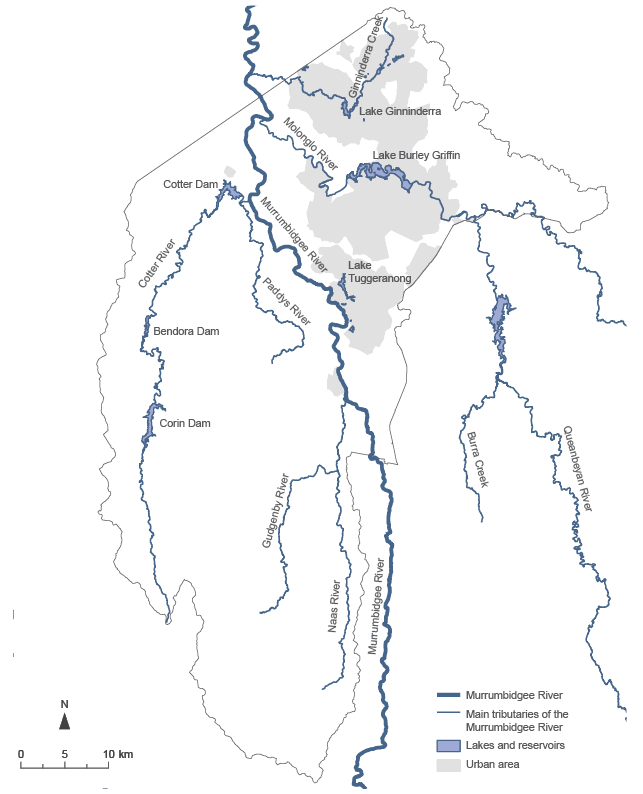

The Great Artesian Basin is our greatest inland water resource, covering 22% of the Australian continent. Putting control of all that land, and water, into the hands of a foreign commercial enterprise, is foolhardy. The mine will take at least 270 billion litres of groundwater over the life of the mine; put aquifers of the Basin at risk; and dump mine polluted wastewater into the Carmichael River.

It will threaten ancient springs and 160 wetlands that provide permanent water during drought, and leave behind 6 unfilled coal pits that will drain millions of litres of groundwater, forever. Adani’s associated water licence allows unlimited access to groundwater for 60 years for free. Putting control of all that land, and water, into the hands of a foreign commercial enterprise, is foolhardy.

The Great Coal Swindle. Pollution from burning coal is the single biggest contributor to dangerous global warming, threatening our way of life. In Australia, ‘black lung’ disease has recently re-emerged among coal miners, with at least 19 workers in Qld identified with the disease. The coal from the Carmichael mine will be burnt in India where 115,000 people die from coal pollution every year. Developing renewable energy is more responsible for the environment and more energising for the economy.

The Great Employment Myth. There are 69,000 tourism jobs related to the Great Barrier Reef, which rely on a healthy Reef. There are thousands of farming jobs in the inland areas under threat. The Adani mine and associated works will pollute, despoil, and degrade both the land area and the associated offshore seas, impacting hugely on the Reef. Adani claims the mine will bring employment opportunities to the region, but in reality there will be far fewer jobs if the mine goes ahead. The mine will decimate local employment opportunities.

The Great Commercial Swindle. Adani companies are under investigation for tax evasion, corruption, fraud, and money laundering. Nine of the 20 Adani subsidiaries registered in Australia are ultimately owned by an entity registered in the infamous Cayman Islands tax haven. That is beyond the regulatory reach of the Australian Government.

Adani Group companies have an appalling environmental track record with a documented history of destroying the environments and livelihoods of traditional communities in India, and failure to comply with regulations. They will do the same in Australia if the mine goes ahead.

There are other reasons—environmental, economic, political—that mean we should not go ahead with the mine.

And, for me, there is a fundamental theological principle undergirding this issue: God’s good creation is in our hands; we are called to act responsibly, to care for, honour, and respect that creation. That means that we act to lessen our carbon footprint, restructure our energy infrastructure to grow renewable sources, and refresh our national policies so that we prioritise the planet over personal preferences.

The Uniting Church has affirmed, “We seek the flourishing of the whole of God’s Creation and all its creatures. We act to renew the earth from the damage done and stand in solidarity with people most impacted by human induced climate change. Government, churches, businesses and the wider community work together for a sustainable future.” (See https://uniting.church/visionstatement2019/)

The Church has issued a Vision Statement which sets out the following desired Key Actions:

1. A national climate policy that drives down greenhouse gas pollution, including no new coal or gas mining in Australia and investment in renewable energy.

2. Just and sustainable transition for communities currently dependent on fossil fuel industries for employment, towards more environmentally sustainable sources of income.

3. Equitable access to renewables for all Australians.

4. Policies which support people and nations that are most vulnerable to climate change.

There is No Planet B. We have no choice but to #StopAdani.

![“Resembling the park lands [of a] gentleman’s residence in England”](https://johntsquires.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/img_0170.jpg?w=1200)