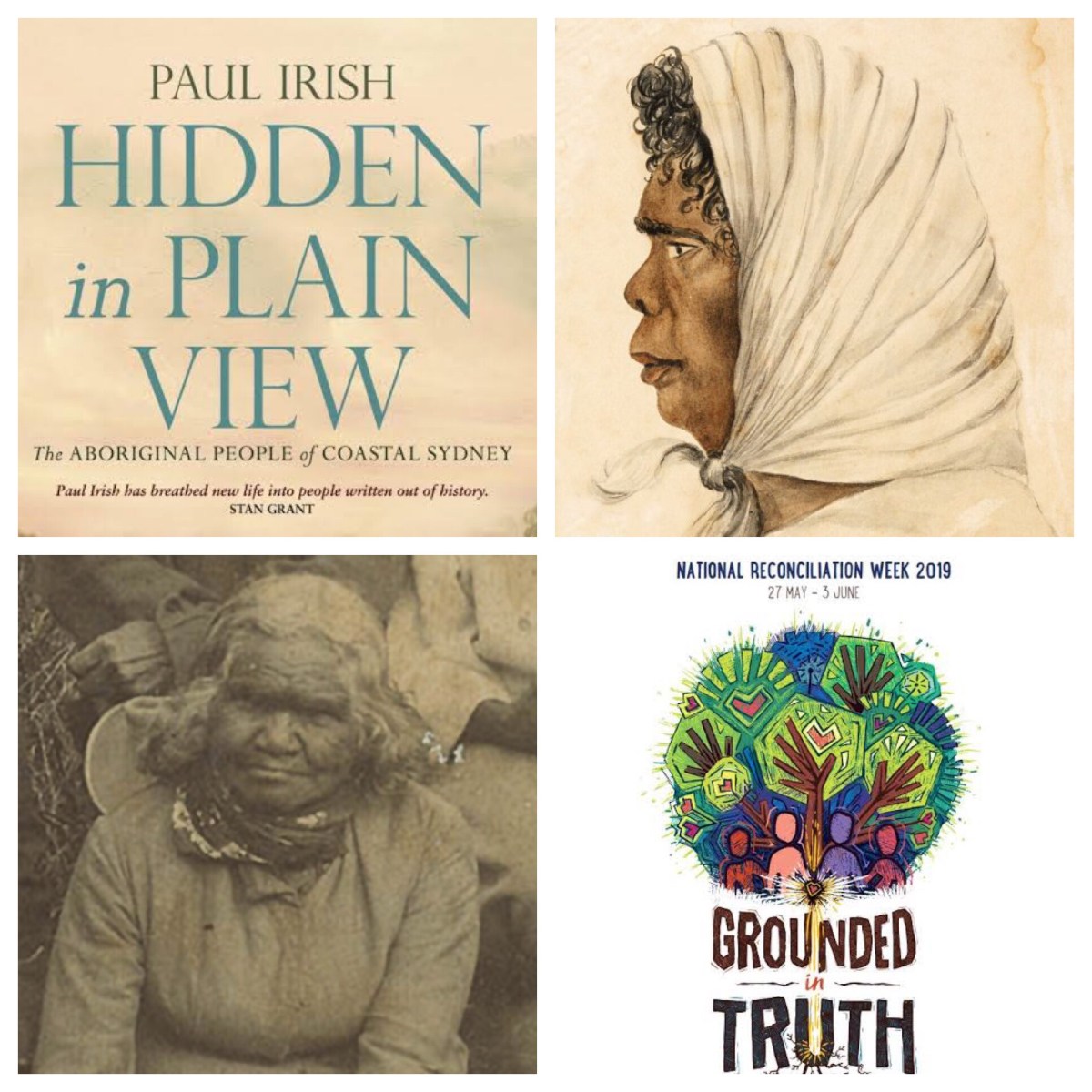

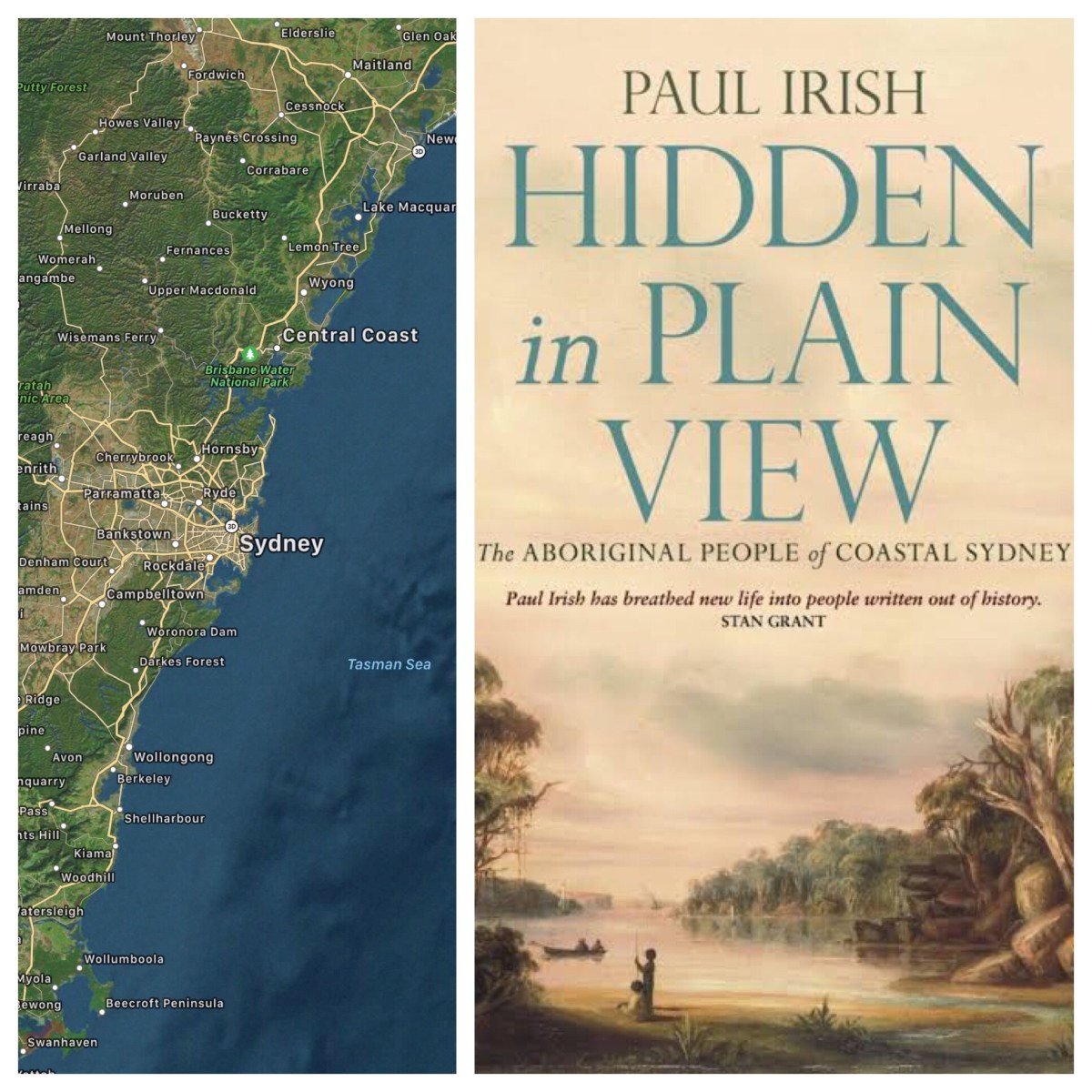

As well as known Aboriginal men who were leaders of their clans and figured in ongoing relationships with the British colonisers in the coastal Sydney area, there are Aboriginal women who are recorded in the early colonial records. Paul Irish recounts what is known about some of them, in his book “Hidden in Plain View”.

Cora Gooseberry was the widow of Bungaree (see https://johntsquires.com/2019/05/30/reconciliation-on-the-land-of-australia-bungaree-and-mahroot/). She was born around 1777 and lived until 1852. Cora was a well-known identity in the Sydney streets. Born as Carra or Kaaroo, she was the daughter of Moorooboora, leader of the Murro-Ore (Pathway Place) clan, named from muru (pathway) and Boora (Long Bay).

Irish reports that Gooseberry’s mob, including Ricketty Dick, Jacky Jacky and Bowen Bungaree, camped in the street outside Sydney hotels or in the Domain, where they engaged with the British invaders by giving exhibitions of boomerang throwing. In July 1845, in exchange for flour and tobacco, Cora Gooseberry took Angas and the police commissioner W.A. Miles on a tour of Aboriginal rock carvings at North Head and told them ‘all that she had heard her father say’ about the places where ‘dibble dibble walk about’, an inference that he had been a koradji from that region. (See http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/gooseberry-cora-12942)

Biddy Giles, 1810 to 1888, lived first in the Illawarra, where she had two daughters to Burragalong, known as Paddy Davis. Davis lived with Biddy from 1850s on a farm at Mill Creek, off the George’s River. Biddy was skilled at fishing and hunting with a pack of dogs. Irish reports that she ran guided tours in the bush land near George’s River down to the Heathcote area, from the 1850s onwards, and then tours to whale engravings near Bundeena in 1860s and 1870s

About the time Paddy died around 1860, Biddy moved to the Georges River, with a new partner, an Englishman called Billy Giles. They lived on the western bank of Mill Creek, known to the Dharawal as Gurugurang, in a farmhouse built earlier by Dr Alexander Cuthill. They had fruit trees, goats and abundant bush tucker from the river and its banks. During the 1860s, Biddy and Billy acted as guides for groups of travellers in shooting or fishing parties, sharing their knowledge of the river and its wildlife, telling stories and sharing skills. These trips ranged from Mill Creek east all the way to the ocean and south into Dharawal country as far as the Shoalhaven.

Some of these travellers wrote accounts of their trips with Biddy, marvelling at her unfailing ability to find fish, her control of her hunting dogs and the skill with which she could rustle up a delicious meal from local produce. (See https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/giles_biddy)

Such women are fine models for us to ponder during this National Reconciliation Week.

(In the picture, Cora Gooseberry is top right, Biddy Giles is bottom left.)

See also

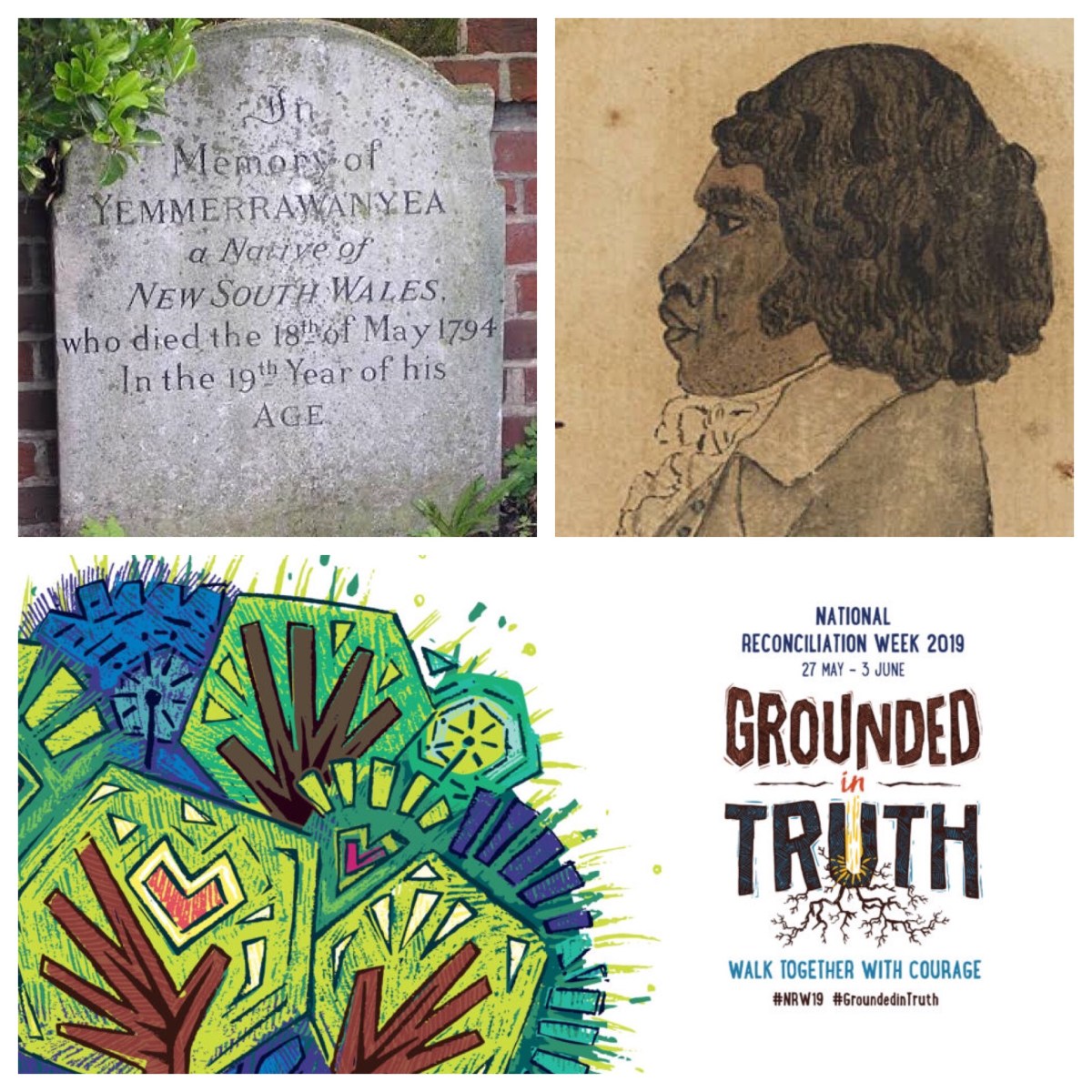

https://johntsquires.com/2019/05/27/we-are-sorry-we-recognise-your-rights-we-seek-to-be-reconciled/

https://johntsquires.com/2019/05/28/reconciliation-on-the-land-of-australia-learning-from-the-past/

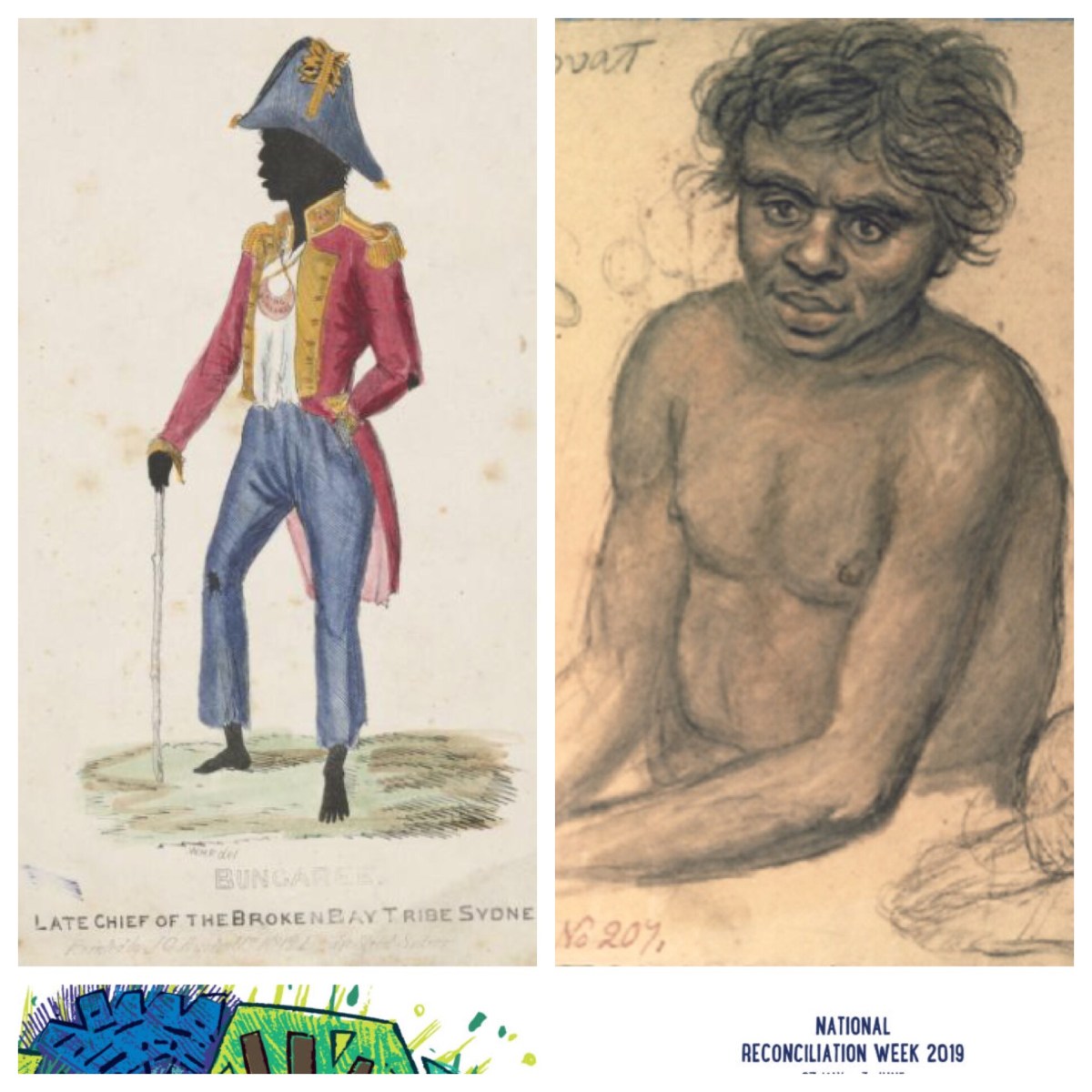

https://johntsquires.com/2019/05/30/reconciliation-on-the-land-of-australia-bungaree-and-mahroot/

On the doctrine of discovery: https://johntsquires.com/2018/08/13/affirming-the-sovereignty-of-first-peoples-undoing-the-doctrine-of-discovery/