This coming Sunday, we read the story of David’s adultery with Bathsheba (2 Sam 11:1–15). This story is known and remembered through the ages—although it is often misinterpreted, in explanations that “blame the woman” for what, in the text, is clearly a series of actions undertaken explicitly by the man who has power, the man who decides to “take” the woman.

In this regard, this ancient story resonates strongly with the experience of millions, if not billions, of women in the modern world. The #MeToo movement attests to the ongoing occurrence of sexual exploitation and abuse of women by men with power. It continues to take place every day, in every country, around the world. Abusive behaviour, abusive words, sexual pressures, rape and domestic violence—the list goes on and on. It is a sad indictment of the overwhelming numbers of males who continue to perpetrate this sad way of being.

Estimates published by the World Health Organisation indicate that “globally about 1 in 3 (30%) of women worldwide have been subjected to either physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence or non-partner sexual violence in their lifetime. Most of this violence is intimate partner violence. Worldwide, almost one third (27%) of women aged 15-49 years who have been in a relationship report that they have been subjected to some form of physical and/or sexual violence by their intimate partner.”

The report concluded that “The social and economic costs of intimate partner and sexual violence are enormous and have ripple effects throughout society. Women may suffer isolation, inability to work, loss of wages, lack of participation in regular activities and limited ability to care for themselves and their children.” See https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women

In my previous post, I explored the figure of Bathsheba. In this post, attention turns to David. I have already flagged my support for the view that it was the sin of David, rather than any sinfulness by Bathsheba, which lies at the root of this story. Yet we need to note that it is not just one sin of David which the narrative reports; there are two different (albeit related) and equally serious sins that he committed. See

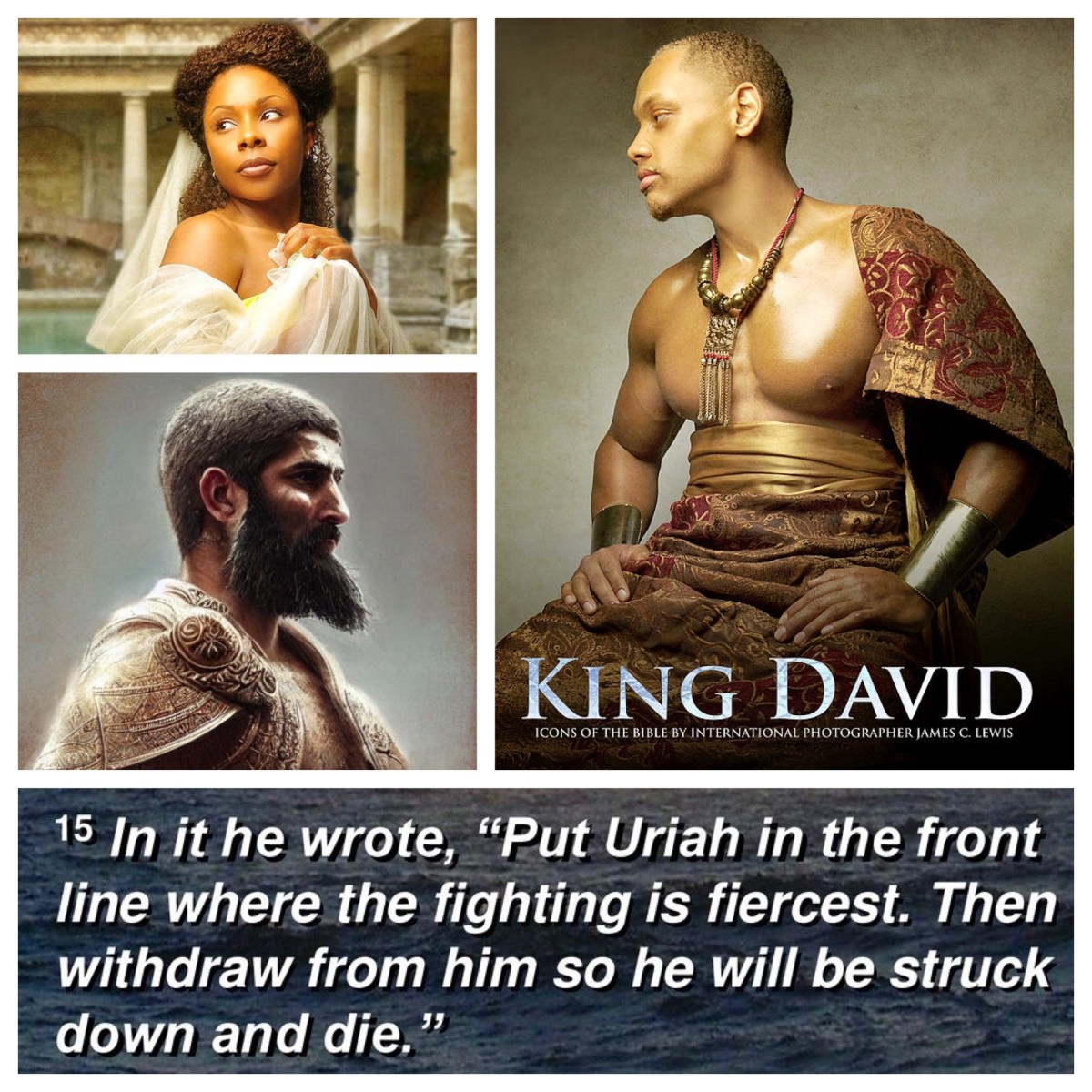

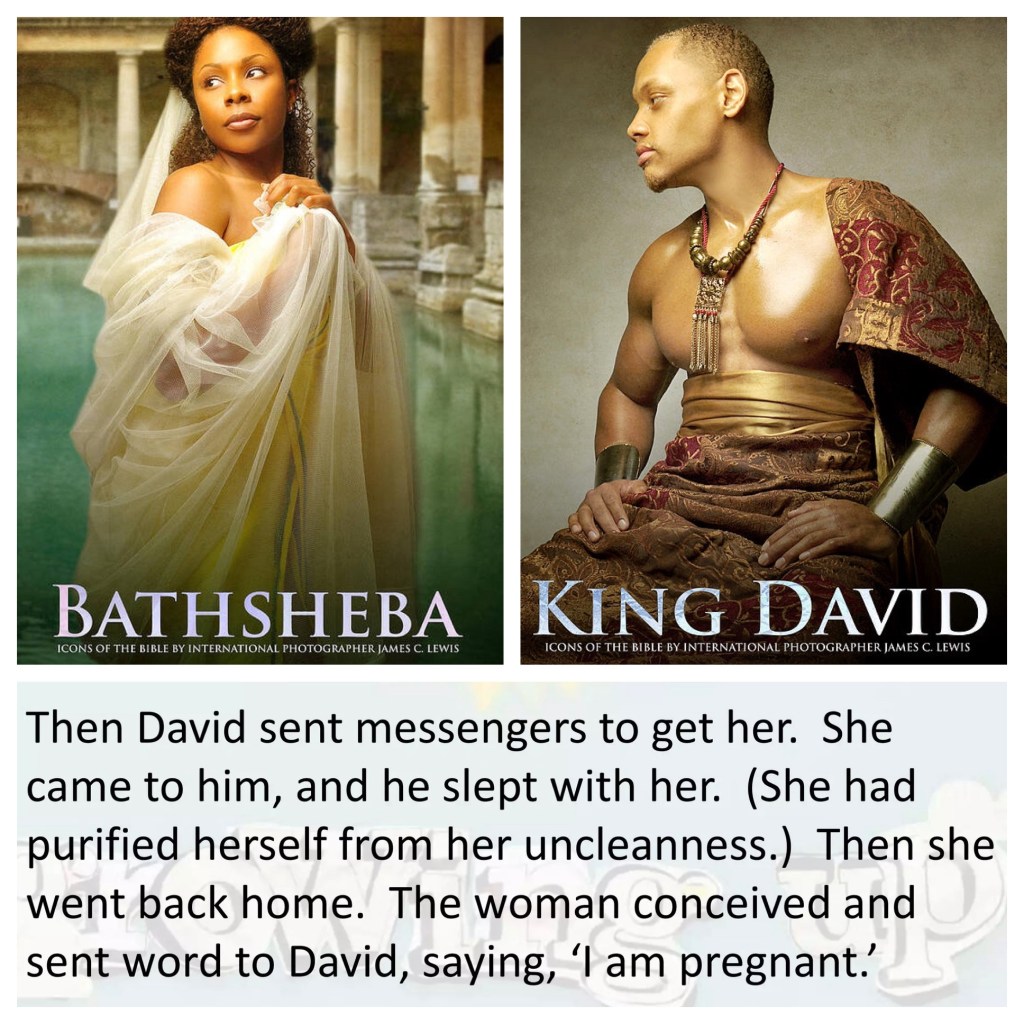

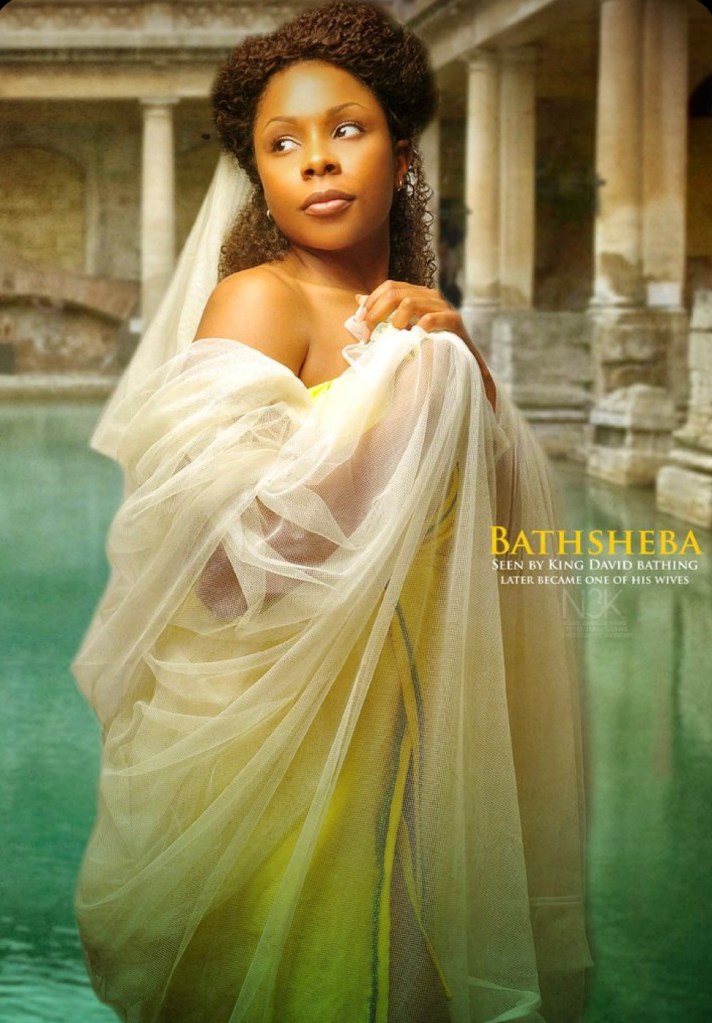

The first sin involves Bathsheba. David has sexual relations with her; “he sent messengers to get her, and she came to him, and he lay with her” (2 Sam 11:4). This resulted in the birth of a child (11:5); sadly, the child later died (12:15–19). What was the nature of this liaison David engineered with Bathsheba? Was it “a fling”? “an affair”? an abuse of his power? Was it adultery? Was it, even, as some maintain, rape?

Richard Davidson has written a fascinating article, “Did King David Rape Bathsheba? A Case Study in Narrative Theology”, published in the Journal of the Adventist Theological Society, 17/2 (Autumn 2006): 81–95. It is also accessible online (see link below). Davidson opens his careful analysis of the story by reporting ways that interpreters have sought to minimise the sin that David committed.

He notes that various commentators have claimed that Bathsheba is “a willing and equal partner to the events that transpire” (Randall Bailey), there is a possible element of “feminine flirtation” (H.W. Hertzberg), Bathsheba showed “complicity in the sexual adventure” (Lillian Klein), or “the text seems to imply that Bathsheba asked to be ‘sent for’ and ‘taken’” (Cheryl A. Kirk-Duggan).

Davidson will have nothing of this minimising of what David has done, from those who claim that Bathsheba was somehow complicit. The narrative, he concludes, “represents an indictment directed solely against the man and not the woman, against David and all men in positions of power (whether civil or ecclesiastical or academic) who take advantage of their ‘power’ and victimize women sexually. Power rape receives the strongest possible theological condemnation in this narrative.” See https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1174&context=jats

Indeed, the text could not be clearer; the chapter ends with the definitive conclusion, “the thing that David had done displeased the Lord” (2 Sam 11:27b). The two key factors that Davidson cites in support of this “displeasing thing” actually being a rape are based on his reading of the Hebrew text.

First, he notes that “the fact that the narrator still here calls her ‘the wife of Uriah’ implies her continued fidelity to her husband, as does the reference to Uriah as ‘her lord/husband’. By using the term ba’al [lord] to denote her husband, the narrator intimates that if ‘Uriah is her lord’, then David is not”.

Davidson supports this by noting that the narrator “carefully avoids using the name of Bathsheba throughout the entire episode of David’s sinning” and suggesting that this “makes her character more impersonal, and thus perhaps further conveying the narrator’s intention of suggesting that Bathsheba wasn’t personally responsible.”

This anonymising of Bathsheba in the story is not unusual in terms of other biblical narratives, where women in the story go unnamed. But the reference to Uriah as her ba’al [lord] does suggest a distancing from David, even though he is king,with seemingly unfettered power.

Second, he observes that at the conclusion of the story, after Uriah had been killed and Bathsheba had completed her mourning rites, “David again sent for Bathsheba and ‘harvested’ her”. He comments on the Hebrew word used here, asap; he maintains that it was usually used “for harvesting a crop or mustering an army”, and here it “further implies King David’s capacity for cold and calculating ruthlessness, which was exercised in his power rape of Bathsheba and subsequent summoning (“harvesting”) of her to the palace.”

That might be pushing the point too far. The word asap is indeed used many times to refer to picking crops and taking them home, and also to gathering men for an army. But it is used on some occasions simply to refer to gathering a person to take them to another person, without any sense of duress or force being involved.

We find such a “neutral” sense on the death of Jacob (Gen 49:33), when Saul recruits soldiers for his army (1 Sam 14:52), in the command to care for a neighbour’s lost animal (Deut 22:2), in the psalmist’s words that “if my father and mother forsake me, the Lord will take me up” (Ps 27:10), and in Huldah’s comforting words to King Josiah, “you shall be gathered to your grave in peace; your eyes shall not see all the disaster that I will bring on this place” (2 Ki 22:20).

And there is certainly no direct indication of physical force or emotional abuse in the report of the initial act of intercourse between David and Bathsheba. David sent messengers and “she came to him, and he lay with her” (2 Sam 11:4). But, as already noted, she really had no choice in the matter.

Today, we would call what David did coercive control, and would consider there are implicit “red flags” which the text does not make explicit. Certainly, we cannot argue for any lessening of David’s responsibility by any suggestion of any complicity on the part of Bathsheba. She was forced to have sex; she was raped by the most powerful man in the kingdom.

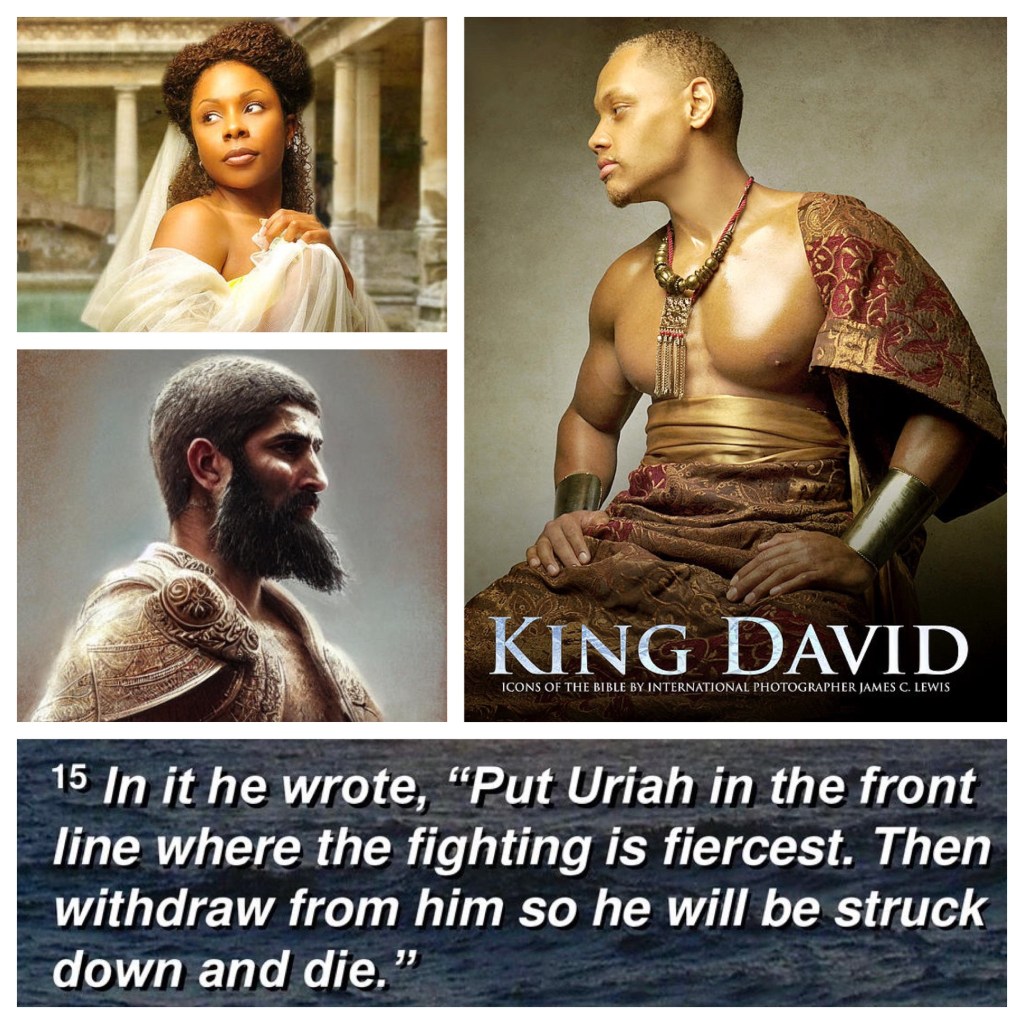

The second sin committed by David is not “up close and personal” like his rape of Bathsheba. It is perpetrated “at arm’s length” by others, acting at his command. Indeed, whilst the death of Uriah occurs some 150 kms or more away on the battlefield, at Rabbah, where David’s forces were besieging the Ammonites in that city, it is the command that David makes in Jerusalem, over 150km away, that reveals his sin.

And as noted in the previous blog post, David should have been on the front line with his troops; it was spring, “the time when kings go out to battle” (2 Sam 11:1), yet David is leisurely strolling on his roof, looking down to see the happenings in the nearby houses below.

The text is, once again, crystal clear about the initiative that David took and the plot that he himself had concocted: “David wrote a letter to Joab, and sent it by the hand of Uriah. In the letter he wrote, ‘Set Uriah in the forefront of the hardest fighting, and then draw back from him, so that he may be struck down and die.’ As Joab was besieging the city, he assigned Uriah to the place where he knew there were valiant warriors. The men of the city came out and fought with Joab; and some of the servants of David among the people fell. Uriah the Hittite was killed as well.” (2 Sam 11:15–17).

Whilst David does not physically murder Uriah, he issues the order, faithfully transmitted by his general, Joab, and executed by “the men of the city” (11:17). He bears ultimate responsibility. No commentator attempts to extricate him from this. And curiously, we note that the lectionary stops before the death of Uriah is reported; it ends with David’s command in his letter (v.15). It seems a strange marking of the passage. We need to read and hear the story at least through to the denouement of David’s plan: “Uriah the Hittite was killed as well” (v.17).

The situation regarding the clinical way that David carries out his plan is intensified—made worse, or made perfectly clear—by the fact that, in between his rape of Bathsheba and the murder of Uriah, David deliberately courts Uriah in a show of friendship. He asked for Uriah to leave the battlefield and come to him (v.6), enquired about the progress of the war (v.7), granted him a time of leave and sent a gift to him (v.8), and wined and dined him with a feast (v.13).

David’s intentions are clear; he wants Uriah to “go down to his house”—presumably in order for him to sleep with Bathsheba, and thus explain her pregnancy. However, Uriah twice does not do so (vv.9, 13). On the first occasion, he sleeps rough in solidarity with his men on the battle field (v.11). He explicitly states that he does not intend to sleep with his wife. On the second occasion, David has made him drunk, so he sleeps it off “on his couch with the servants of his lord” (v.13).

That Uriah “did not go down to his house”, stated twice, declares his resolute character. He will not take advantage of this unexpected call back to the comfort of the city; he maintains his integrity as one of David’s “warriors”. This is in stark contrast to David’s clinical, self-interested scheming—first, to gain Bathsheba, when she catches his eye, and then to dispatch Uriah, to have him out of the way.

We all know about David’s illicit liaison with Bathsheba—even if, as I have noted, not everybody accepts his total responsibility for what he did, and not everybody accepts that he did actually rape her. He is clearly remembered for this sin; as well as this story, the superscription to Psalm 51 reinforces this. (See more in next week’s blog.)

David’s arrangement of the murder of Uriah ought also to be known and remembered through the ages. He acted with cunning, deception, cruelty, and self-interest. It is a scathing indictment of a powerful male figure—sadly, he is just one of so, so many throughout history.

Writing in With Love to the World, Amel Manyon considers the character of David: “David was a man of faith, but he was not acting responsibly as the leader of his army when he decided to stay in Jerusalem. He was expected to do his duty—at least meditating on the law of Moses, praying, or writing psalms. Perhaps he was bored, with nothing to do?” (That’s a rather generous assessment of David’s character, I think.)

Manyon rightly notes that David “used his positional power to force Bathsheba into immorality. At the time, Bathsheba would have had no choice but to obey her leader, the King—but that is not an excuse for the leader to justify his actions. When David sent for Uriah, husband of Bathsheba, he had an opportunity to learn about leadership. Uriah had not allowed himself to enjoy time with his wife when his fellow soldiers were exposing their lives to danger for their country; David under such circumstances indulged in sinful lust and criminal actions.” The contrast is indeed striking.

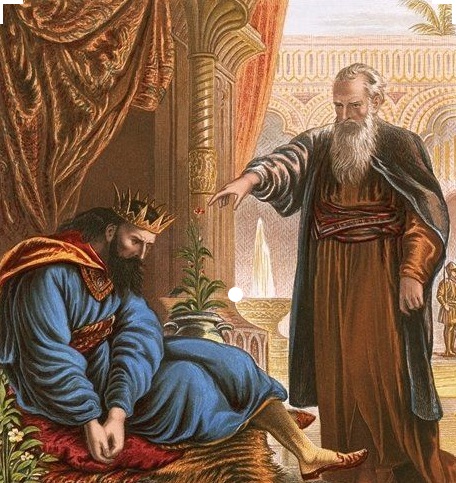

Manyon relates what she says about David to contemporary leaders, noting that “we should not use our power to take what does not belong to us.” It’s a simple, succinct application. Indeed, this is what is conveyed in next week’s lectionary passage (2 Sam 12), where Nathan confronts David with the extent of his sin—he used his power to grasp what belonged to another man.

A very generous assessment of David is offered later in the long narrative history telling of the Kings of Israel and Judah. During the assessment of the reign of Abijam, a great-grandson of David and the second King of Judah after the kingdom was split in two at the death of Solomon, the narrator assesses the poor character of Abijam as one who “committed all the sins that his father did before him; his heart was not true to the Lord his God, like the heart of his father David” (1 Ki 15:3).

The narrator notes that, despite this flawed character, Abijam was able to rule for three years only because the Lord looked favourably upon David, of whom it is said, “he did what was right in the sight of the Lord, and did not turn aside from anything that he commanded him all the days of his life, except in the matter of Uriah the Hittite” (1 Ki 15:5). How interesting—and telling—that it is the sin against Uriah that is mentioned, and not the sin against Bathsheba.

What model of leadership is offered by this tale? The initial compilers of the sagas of Israel could have skimmed over this episode, allowing David to be painted in a resolutely positive light. Indeed, this is what the compiler(s) of 1–2 Chronicles does. (There is no story about David and Bathsheba in these books; it is as if it didn’t happen!) But the story is included in 2 Samuel; and David the Adulterer and David the Murderer sit alongside David the Harpist and David the Psalmist in Jewish and Christian traditions. He exemplifies the complexities of every human being. He is Everyperson. We should listen carefully, and learn from the stories told about him.

*****

Once again, I am grateful to Elizabeth Raine for her comments on this post, informed by her careful study of the text.

With Love to the World is a daily Bible reading resource, written and produced within the Uniting Church in Australia, following the Revised Common Lectionary. It offers Sunday worshippers the opportunity to prepare for hearing passages of scripture in the week leading to that day of worship. It seeks to foster “an informed faith” amongst the people of God.

You can subscribe on your phone or iPad via an App, for a subscription of $28 per year. Search for With Love to the World on the App Store, or UCA—With Love to the World on Google Play. For the hard copy resource, for just $28 for a year’s subscription, email Trevor at wlwuca@bigpond.com or phone +61 (2) 9747-1369.