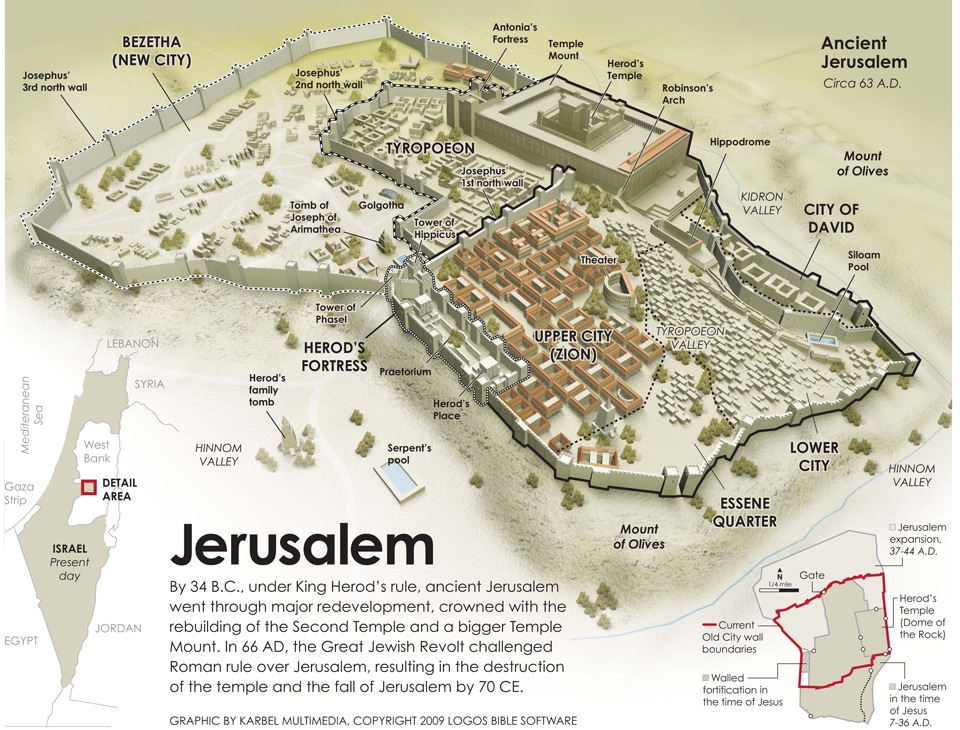

Jerusalem. It features in the passage that is proposed by the lectionary for reading and reflection in worship this coming Sunday (2 Sam 5:1–10). Jerusalem. The name of the city evokes all manner of responses.

In our own time, Jerusalem has been the focal point for bitterly-contested claims about land. On a high point in the city, the sacred Jewish site of Mount Zion, on a base which formed the foundation for the Temple built two millennia ago, sits the gleaming gold dome of a Muslim holy building. It has been contested territory for decades, ever since the modern state of Israel was established. Today, both Israeli Jews and Palestinian Muslims claim Jerusalem as the capital city of their contested territory.

Jerusalem has significance in Jewish tradition as the place where Abraham was said to have been tested by a command to sacrifice his son, Isaac (Gen 22), where David based his kingdom over a united Judah and Israel (2 Sam 5), where Solomon built a temple to the Lord God (1 Ki 3:1; 8:1–9:25), and where the returning exiles came to focus their rebuilding of religion and society after their years in Babylon (Ezra 1—3; Neh 7—8). The more highly conservative of Jews today anticipate that, when the Messiah comes, he will oversee the rebuilding of the Temple in Jerusalem.

Jerusalem also has significance in Islam, as the last place visited by the Prophet Mohammed before he ascended into the heavens (Quran 17:1), as well as being a key place in the events to take place at the end of the world. The city is called Al-Quds, meaning “the noble, sacred place”. It is reported that Mohammed instructed faithful people to make pilgrimages to three places: Mecca, Medinah, and Jerusalem. The Dome of the Rock, with its golden-topped mosque, is a stunning reminder of the importance of the city to Muslims.

And Jerusalem has gained central significance in Christianity because it was the place where Jesus was arrested, tried, crucified, and buried (Mark 14—15 and parallels); where, in some traditions, his earliest disciples laid claim to having seen him alive (Luke 24:33–53; John 20:19–29); and where, according to Luke’s orderly narrative, the first gathering of “apostles and elders” made decisions about “what God had done … among the Gentiles” (Acts 15:6–29).

So the passage for this coming Sunday (2 Sam 5:1–10) touches on a deeply symbolic element of the story, not only of ancient Israelite religion and modern Judaism, but also of contemporary Christian and Muslim sensitivities about Jerusalem.

allocated to Jews, Christians, Muslims, and Armenians

(Encyclopedia Britannica)

The history-like narratives that form the books in the extended series of Exodus, Numbers, Joshua, Judges, 1–2 Samuel, and 1–2 Kings tell the story, mythologised and valorised, of the development of Israel from its early days. These narratives most likely originated as oral stories, told and retold over the years, coming into written form many centuries after they were first told. We have access to these stories only through the written compilation that we have in Hebrew Scripture, most likely finalised in the time leading up to or during the exiles of the people of Israel and Judah from the 7th and 6th centuries BCE.

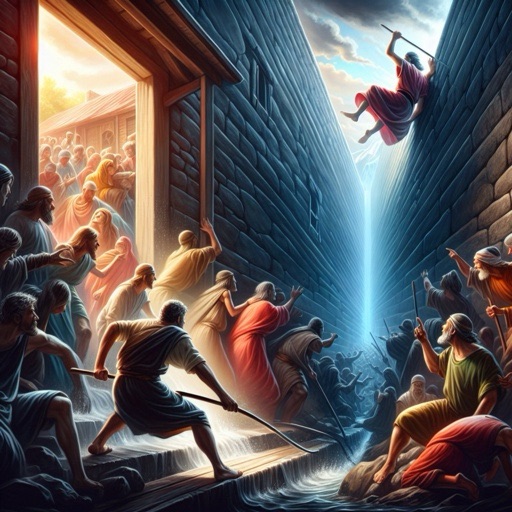

The lectionary selection this Sunday (2 Sam 5:1–10) tells of the taking of Jerusalem by the army of King David, soon after the elders of Israel had anointed him as king (2 Sam 5:3). His rule, we are told, would last for another 33 years; coming after the seven years that he had already ruled Judah, this would make for forty years as king (2 Sam 5:4-5). And in these biblical narratives, “forty years” is the way of describing “a long, long time”. The dominance of David over his kingdom is signalled in this claim.

In listening to this passage, we need to remember that we are not dealing with a precise and accurate historical account of David’s taking control of the city of Jerusalem; not that such an objective factual account could ever exist, for all “history” is told from a specific perspective, and other perspectives on the same events are equally possible and valid. So this is an account from a later time, told to explain and justify the place that Jerusalem has held amongst “the house of David”, the people of Israel.

The city forms a stronghold for David, as he consolidates his power. This is but one in a number of battles that David engaged in, beginning with his his centre-stage role in the ongoing war against the Philistines, when he slew the giant Goliath (1 Sam 17). David held power through years of wrangling with Saul, before his dominance was secured. His earlier years as ruler of the united kingdom continued to be unsettled. The narrator cites a song that was later sung about these two kings, as their troops battled each other, as well as mutual enemies: “Saul has killed his thousands, and David his ten thousands” (1 Sam 21:11).

After fighting the Philistines, Saul has 85 priests of Nob slaughtered (22:1–19); David leads his men in “raids on the Geshurites, the Girzites, and the Amalekites … leaving neither man nor woman alive” (27:8–11). He did battle once again with the Philistines (29:1–11); the narrator then provides a list of the many towns “where David and his men had roamed” (30:27–31). Presumably in those places they had murdered and pillaged as well.

2 Sam 8–12 lists ongoing battles in which David features: attacking the Philistines yet again (8:1), then the Moabites (8:2), the Syrians under Hadadezer of Zobah (8:3–8), the Edomites (8:13–14), the Ammonites (10:14) and the Arameans (10:15–19), and then the Ammonites once again (12:26–31). The conquest of Jerusalem from the Jebusites that features in the passage we read this coming Sunday (2 Sam 5:1–10) is but one of many armed conflicts that David leads.

It is ironic that the name of the city, Jerusalem, most likely means “city of peace”; the word combines two Semitic roots, yry, meaning “foundation”, and shlm, meaning “peace”. The name signifies that the city provides the foundation for peace. Yet the city was (and sadly, today, continues to be) anything but a city of peace. Even in his day, David used the site as a means to his own political ends; he takes the city from its Jebusite inhabitants and builds a foundation where God’s holiness could be reinforced and celebrated.

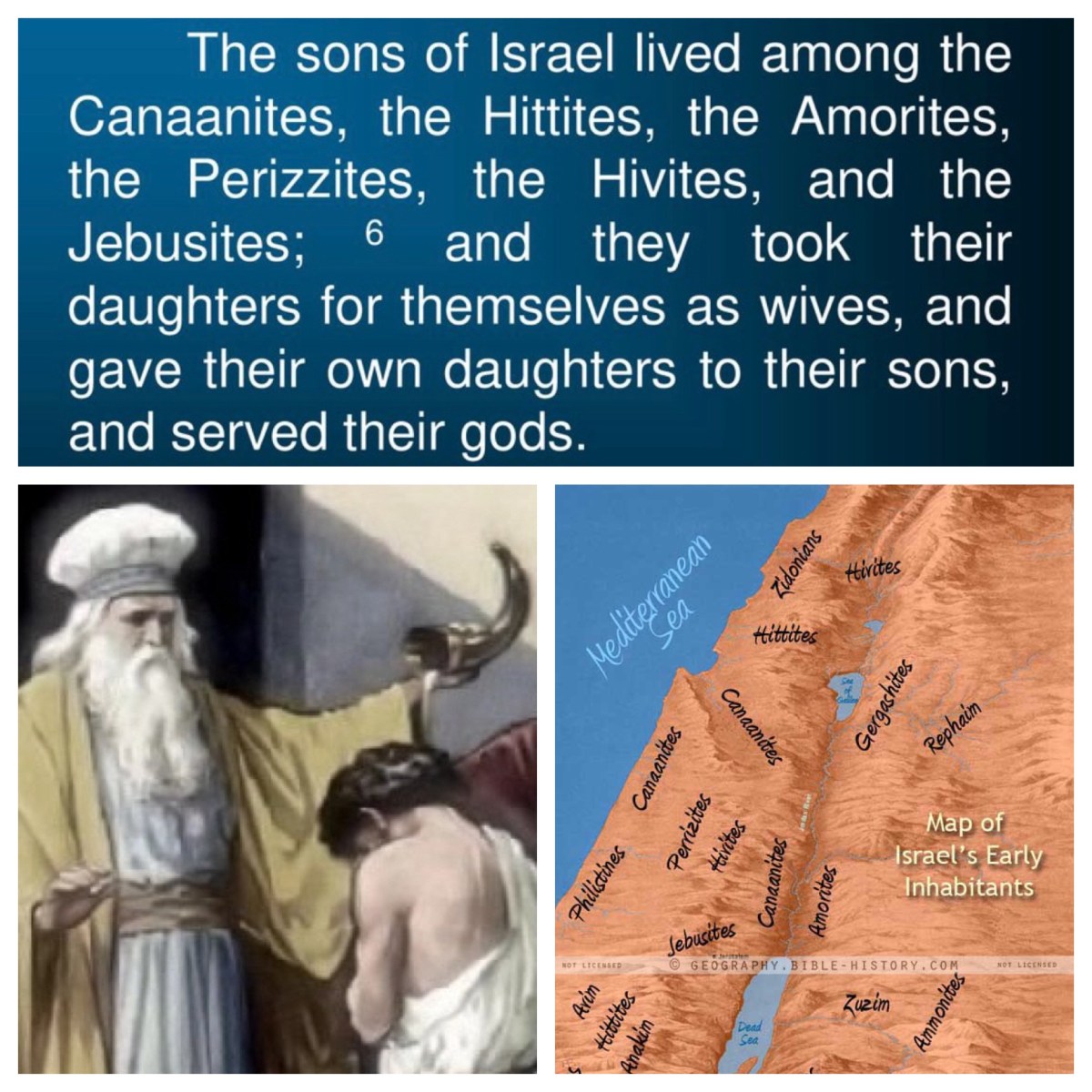

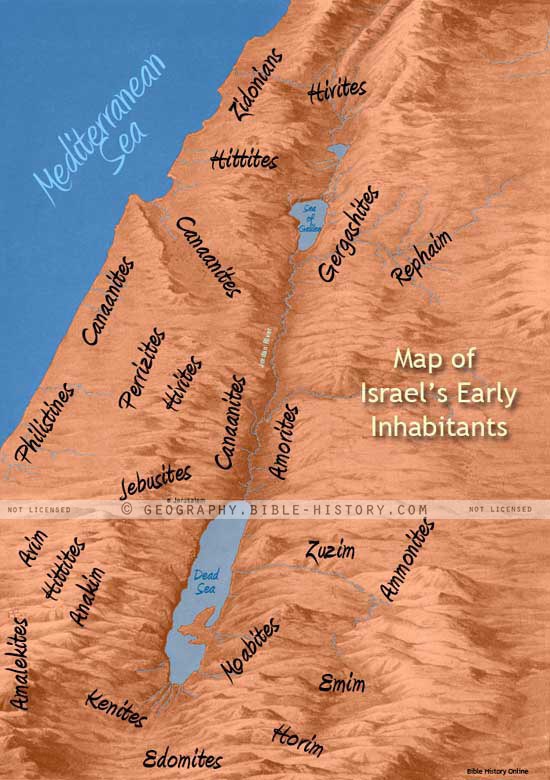

The Jebusites had long been the inhabitants of the city named in scripture as Jerusalem. This people appear with regularity in the list of peoples who were “the inhabitants of the land” that was initially, so the story goes, promised to Abraham and his descendants: “to your descendants I give this land, from the river of Egypt to the great river, the river Euphrates, the land of the Kenites, the Kenizzites, the Kadmonites, the Hittites, the Perizzites, the Rephaim, the Amorites, the Canaanites, the Girgashites, and the Jebusites” (Gen 15:18–21).

In the book of Exodus, the Lord God declares of the Israelites in Egypt, “I know their sufferings, and I have come down to deliver them from the Egyptians, and to bring them up out of that land to a good and broad land, a land flowing with milk and honey, to the country of the Canaanites, the Hittites, the Amorites, the Perizzites, the Hivites, and the Jebusites” (Exod 3:7–8; see also 3:17; 13:5; 23:23; 33:2; 34:11).

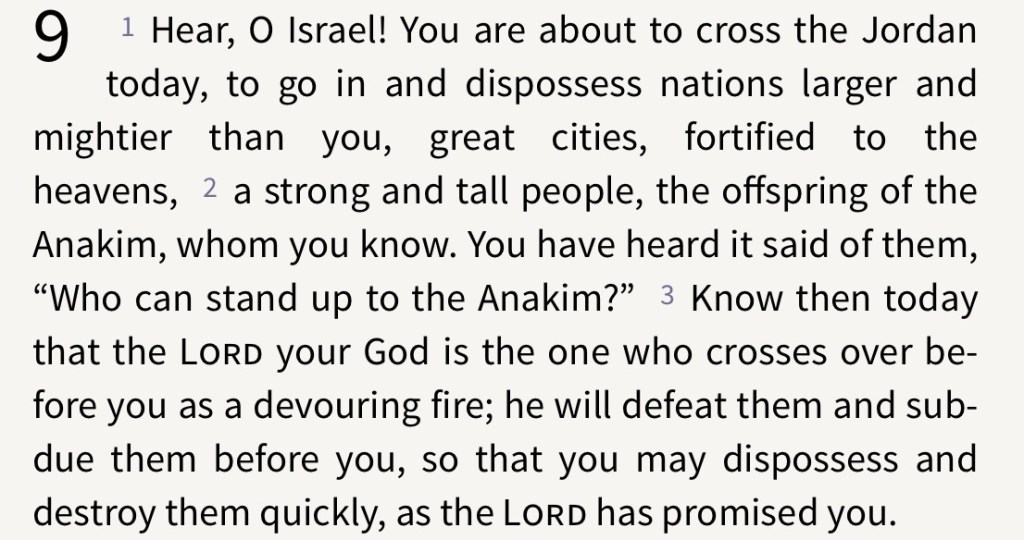

Numbers 32 then purports to give a detailed account, in advance, of the various kingdoms and their cities that will be conquered and divided up amongst the twelve tribes of Israel, as they capture them, dispossess the people (see v.39), and rename the towns and villages. The command to “dispossess” the people of their land runs through Moses’s long speech that is reported in Deuteronomy (see Deut 7:17; 9:1–3; 11:1–3; 12:29; 31:3).

The instructions are clear: “You must demolish completely all the places where the nations whom you are about to dispossess served their gods, on the mountain heights, on the hills, and under every leafy tree. Break down their altars, smash their pillars, burn their sacred poles with fire, and hew down the idols of their gods, and thus blot out their name from their places. You shall not worship the Lord your God in such ways.” (Deut 12:2–4).

Before this speech, as they stand on the threshold of the land of Canaan, the people were hesitant about entering; it was reported, “the people [in Canaan] are stronger and taller than we; the cities are large and fortified up to heaven” (Deut 1:28). The Lord God chastens them and insists they press ahead to enter the land, where they will find “a land with fine, large cities that you did not build, houses filled with all sorts of goods that you did not fill, hewn cisterns that you did not hew, vineyards and olive groves that you did not plant” (Deut 6:10–11). For will give this all to them.

The book of Joshua then recounts the forceful invasion of the tribes of Israel into the land of Canaan, when list of the peoples whom “the living God who without fail will drive out from before you” includes “the Canaanites, Hittites, Hivites, Perizzites, Girgashites, Amorites, and Jebusites” (3:10; see also 12:8; 24:11). The violence perpetrated in this invasion and conquest is made clear by incident after incident in this book and then in the following book of Judges. It was a violent time indeed.

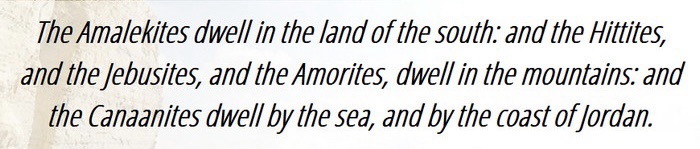

The Jebusites are amongst the peoples identified in the genealogical lists of Genesis as the descendants of Canaan (Gen 10:15–18); in Numbers, we learn that “the Amalekites live in the land of the Negeb; the Hittites, the Jebusites, and the Amorites live in the hill country; and the Canaanites live by the sea, and along the Jordan” (Num 13:29).

At one point in the narrative relating to Joshua, the Israelites engaged in battle with the king of Jerusalem and four other kings (Josh 10:1–5); they were put to death (Josh 10:23–27) and the boundary if the land of the people of Judah was said to have gone “up by the valley of the son of Hinnom at the southern slope of the Jebusites (that is, Jerusalem)” (Josh 5:8). However, the account of the towns of Judah concludes with the note that “the people of Judah could not drive out the Jebusites, the inhabitants of Jerusalem; so the Jebusites live with the people of Judah in Jerusalem to this day” (Josh 15:63).

Then, when the book of Judges was compiled, a similar note was included to the effect that “the Lord was with Judah, and he took possession of the hill country … [but] the Benjaminites did not drive out the Jebusites who lived in Jerusalem; so the Jebusites have lived in Jerusalem among the Benjaminites to this day” (Judg 1:19, 21).

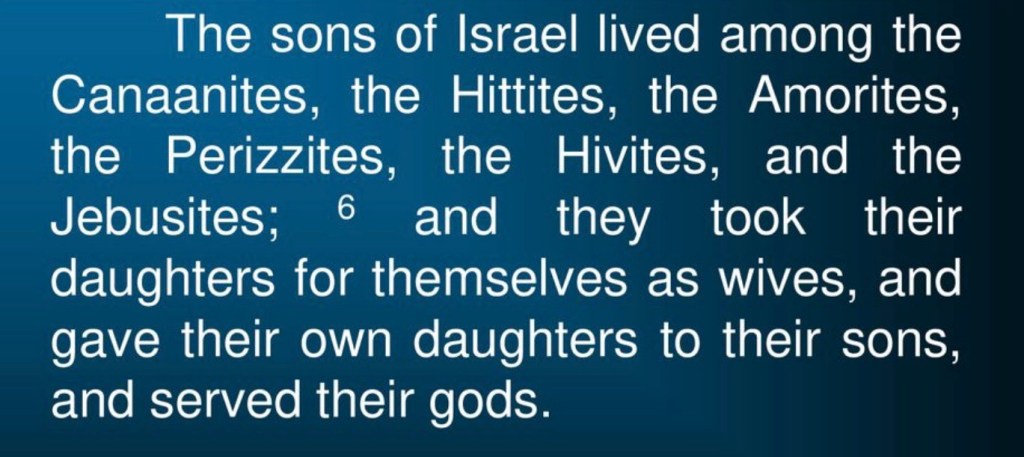

As an explanation as to how “the Israelites did what was evil in the sight of the Lord, forgetting the Lord their God, and worshiping the Baals and the Asherahs” (Judg 3:7), the author of this narrative explains that “the Israelites lived among the Canaanites, the Hittites, the Amorites, the Perizzites, the Hivites, and the Jebusites; and they took their daughters as wives for themselves, and their own daughters they gave to their sons; and they worshiped their gods” (Judg 3:5–6).

So when David comes to the city, the narrative preserved in the scriptures of the Israelites clearly records that he led his army into the city to take “the stronghold of Zion” and to proclaim that it “is now the city of David” (2 Sam 5:7). Hebrew Scripture makes it abundantly clear that the Israelites took over control of this remaining Canaanite settlement by force, just as earlier generations of Israelites had invaded and conquered the people of the wider territory of Canaan, and then waged war against the Philistines.

The narrative had earlier reported that the youthful David, after he had fought and killed the Philistine giant, Goliath, had taken Goliath’s head in triumph into Jerusalem (1 Sam 17:54). However, at this point the narrative had not recorded the transfer of power in Jerusalem from the Jebusites to the Israelites. So this claim is a somewhat anachronistic note, most likely influenced by the understanding that Jerusalem would become the central location of importance for David’s kingdom. (It would be like an Australian talking about going to Canberra in the late 19th century, years before the city was established in 1913.)

In this Sunday’s passage, as David’s Israelite troops approach the city, a curious declaration is made by the local inhabitants, the Jebusites, that any people marked by the imperfection of impurities—the blind, the lame—will be barred from it (v.8). An article on the Jebusites in the Jewish Encyclopedia refers to “a midrash quoted by Rashi on II Sam. v. 6” which explained that “the Jebusites had in their city two figures—one of a blind person, representing Isaac, and one of a lame person, representing Jacob—and these figures had in their mouths the words of the covenant made between Abraham and the Jebusites.” If that was the case, then the Jebusites were presumably trusting in these idols to ensure the security of their city against the Israelite invaders.

See https://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/8542-jebusites

Another view is summarised by Daniel Gavron in his article on “History of Jerusalem: Myth and Reality of King David’s Jerusalem”, in the Jewish Virtual Library. Gavron notes that the eminent Israeli scholar Yigael Yadin had proposed that the people with disabilities were actually to be used as the “first line of defence” against David and his troops.

Yadin draws on the connection between the Jebusites and the ancient Hittite kingdom, noting that there is evidence that soldiers in that kingdom were required to swear an oath of loyalty to the king; should they fail in that loyalty, they would become lame or blind or deaf. So the threat posed by the blind or the lame was to be met by the soldiers of David by their attacking the city—they were used as taunts by David to provoke his men to attack.

See https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/myth-and-reality-of-king-david-s-jerusalem#google_vignette

It is worth noting, perhaps, that the blind and the lame form part of a large cluster of unclean people who were prohibited from bring offerings to the holy God in the Temple (Lev 21:16–18). They are also those whom, according to Jeremiah, the Lord God will come to gather exiles “from the farthest parts of the earth, among them the blind and the lame, those with child and those in labour, together; a great company, they shall return here” (namely, to Jerusalem; Jer 31:8).

Then, of course, they are amongst those who attest to the way that the power of God is at work in Jesus: “the blind receive their sight, the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised, and the poor have good news brought to them” (Matt 11:5; Luke 7:22). Blind and lame came to Jesus by the Sea of Galilee (Matt 15:30–31) and in the Temple in Jerusalem (Matt 21:14); and Jesus instructs his followers, “when you give a banquet, invite the poor, the crippled, the lame, and the blind” (Luke 14:13; also 14:21). They form part of the signs of the kingdom of God which is breaking into the world through Jesus.