This week we move on from the Gospel story, into the narrative of “the things fulfilled among us” that is attributed, by tradition, to Luke, the author of a Gospel and a sequel that we call the Acts of the Apostles. We will hear four excerpts from this second volume in the coming weeks.

Luke, of course, is never identified as the author in either volume; the traditional ascription arises from a combination of factors: Pauline references to “Luke, the beloved physician” (Col 4:14), said to be present with Paul at one point (Phlmn 24, reflected again at 2 Tim 4:11), the references to “we” in the latter chapters of the narrative, and the developing patristic speculation which insisted that each canonical Gosepl needed to be either by one of the apostles or by someone closely associated with one,of the apostles.

The opening verse of this Sunday’s passage links back to the “first volume” (Acts 1:1), naming the same addressee, Theophilus (see Luke 1: 3), and summarising the earlier volume as being about “all that Jesus did and taught from the beginning” (presumably Luke 4:15 onwards) until “the day when he was taken up to heaven” (Luke 24:50–51). The intention for continuity is clear; the volume that follows will trace the development and spread of the movement that Jesus had initiated in Galilee (Luke 6:13–16; 8:1–3; 9:1–6, 10; 10:1–12, 17–20) and which he had then launched on a broader scale in Jerusalem, stretching out “to all nations” (Luke 24:44–49).

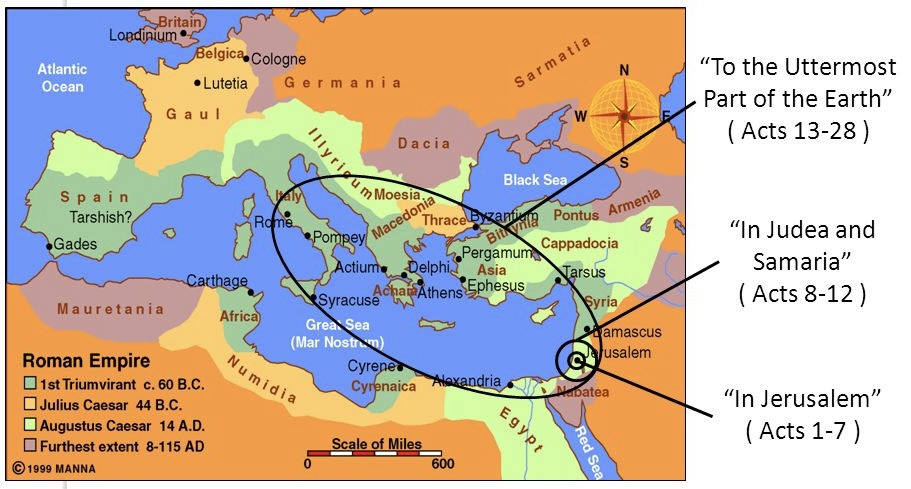

The author sets the scene for recounting various incidents in the life of the community of followers of Jesus who had gathered in Jerusalem. The author—writing a number of decades after the incidents which he reports, and most likely far removed from Jerusalem—tells of how these earliest followers established a pattern of faithful living through their common life, their public witness, and their persistent adherence to their Jewish traditions. The whole section of the second volume is located entirely within Jerusalem (1:4,8,12; 2:5; 4:5; 5:16; 6:7; 8:1) and is concentrated on incidents occurring in that city.

Ten days separate the ascension of Jesus (forty days after Passover, 1:3) from the coming of the Spirit on the day of Pentecost, which is told in the second chapter of volume 2 (2:1, fifty days after Passover). Initially, Jesus instructs the apostles not to depart from Jerusalem (1:4). This instruction keeps Luke’s geographic focus on Jerusalem, in contrast to other traditions concerning the post-resurrection departure of the apostles to Galilee which are inferred (Mark 14:28; 16:7; Matt 26:32) or explicitly told (Matt 28:7,10; John 21).

Remaining in Jerusalem is required so that the apostles might receive the promise (1:4), which is immediately explained as being the holy spirit spoken of by John (1:5; evoking Luke 3:16). The fulfilment of this promise in Jerusalem is, of course, narrated in detail in Acts 2.

Only two things are told of these ten days; already the process of selectivity which shaped the creation of Luke’s Gospel can be seen in this second volume. The first of these is an expanded retelling of the ascension (1:6–11), an event already reported in brief at Luke 24:50–53.

The ascension forms the pivotal moment in Luke’s narrative; it is the hinge between volume 1 (Luke) and volume 2 (Acts), and attention is drawn to the ascension and exaltation of Jesus at a number of points elsewhere (Luke 9:51; 22:69; Acts 2:33; 3:21; 5:31; 7:56). Luke expands this second narrative account of the ascension through the explicit recording of words spoken on that occasion. Key to this version are the last words of Jesus to his followers: a sequence of three clauses which stand as his last words before he ascends into heaven.

The first clause of Jesus’s words in 1:8 turns the question away from Israel, back to the primary theme of God’s sovereignty, with the clear declaration that the times and seasons are under the sovereignty of God who has “set them by his own authority” (1:7). Rather than the political independence of Israel, it is God’s unfettered freedom to act in history which is crucial to his enterprise.

The next clause, “you will receive power when the holy spirit has come upon you” (1:8), is a promise which reinforces the key role of the spirit, as divine agent, throughout this volume (beginning with the events of 2:1–4).

The third clause introduces the important motif of witness (1:22; 2:32; 3:15; 4:33; 5:32; 10:39,41,43; 13:31; 22:15,18,20; 23:11; 26:11,22) and provides a condensed geographical summation of the course of the ensuing events: “in Jerusalem [1:12–8:3] and in all Judaea and Samaria [8:4–12:25] and to the end of the earth [13:1 onwards]”.

The precise referrent of “the end of the earth” is debated. Although Psalms of Solomon 8:15 may suggest that it refers to Rome, it is preferable to see the reference as drawn from Isa 49:6, a verse cited at Luke 2:32 and Acts 13:47. It is thus a poetic statement about the extensive scope of the ensuing events.

These departing words of the Lukan Jesus neatly conjoin the geographical pattern and theological foundation of Acts: from Jerusalem outwards, the divine spirit will enable followers of Jesus to bear witness to the sovereignty of God.

As Jesus ascends into heaven (Acts 1:9–11), the story pivots from the earthly period of Jesus into the time when the movement of those who followed Jesus in that time will begin to form the customs and practices that led to the creation of the church. Luke presents the whole sequence of the death, resurrection and ascension of Jesus as both the climax to his earthly life and the foundation for the time of the church.

This is the issue in focus here: the departure of Jesus by means of his ascension into heaven is actually the moment when Jesus charges his followers to be engaged in mission. The departure of Jesus heralds the start of the church. The (physical) absence of the Saviour brings in the impetus for engaging wholeheartedly with the world which he has (physically) left.

….. to be continued …..

This blog is based on a section of my commentary on Acts in the Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible, ed. Dunn and Rogerson (Eerdmans, 2003). I have also explored the theme of the plan of God at greater depth in my doctoral research, which was published in 1993 by Cambridge University Press as The plan of God in Luke-Acts (SNTSM 76).