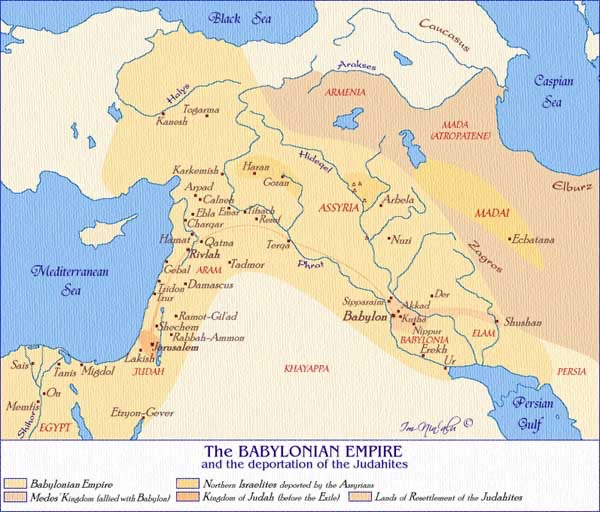

The third section of the book of Isaiah (chapters 56–66) begins with a familiar prophetic announcement: “maintain justice, and do what is right, for soon my salvation will come, and my deliverance be revealed” (Isa 56:1). Written during the period when the people of Judah were returning to their land, to the city of Jerusalem (from the 520s BCE), the book demonstrates what this justice will look like through a series of powerful oracles.

The prophet sounds a vivid counter-cultural note in the midst of the events of his time. He begins with the promise to foreigners and eunuchs that “I will give, in my house and within my walls, a monument and a name better than sons and daughters; I will give them an everlasting name that shall not be cut off” (Isa 56:5). This is a striking contrast to the narrative provided in the books of Ezra and Nehemiah, which tell of the return to the city, the rebuilding of the walls, the renewal of the covenant and the public reading of the Law, the rededication of the Temple—and actions designed to remove foreigners (especially women) from within Israel (see Ezra 10; Neh 13).

Ezra and Nehemiah exhibited a zealous fervour to restore the Law to its central place in the life of Israel. Ezra, learning that “the holy seed has mixed itself with the peoples of the lands” (Ezra 9:2), worked with “the elders and judges of every town” to determine who had married foreign women; the men identified “pledged themselves to send away their wives, and their guilt offering was a ram of the flock for their guilt” (Ezra 10:19). (So much for the importance of families!)

Nehemiah considered that this project to “cleanse [the people] from everything foreign” (Neh 13:30) was in adherence to the command that “no Ammonite or Moabite should ever enter the assembly of God, because they did not meet the Israelites with bread and water, but hired Balaam against them to curse them” (Neh 13:1–2; see Num 22—24). The restoration of Israel as a holy nation meant that foreigners would be barred from the nation.

The oracle at the start of the third section of Isaiah stands in direct opposition to this point of view; “the foreigners who join themselves to the Lord … and hold fast my covenant—these I will bring to my holy mountain, and make them joyful in my house of prayer; their burnt offerings and their sacrifices will be accepted on my altar; for my house shall be called a house of prayer for all peoples” (Isa 56:6–7).

Jesus, of course, quoted this last phrase in the action he undertook in the outer court of the Temple (Mark 11:17). Later, the welcome offered to the Ethiopian court official by Philip, who talked with him about scripture and baptised him, a eunuch (Acts 8:26–38), is consistent with the prophetic words, “to the eunuchs who keep my sabbaths, who choose the things that please me and hold fast my covenant, I will give them an everlasting name that shall not be cut off” (Isa 56:4–5). (From the earliest days, the church practised an inclusive welcoming of diversity that was consistent with this prophetic declaration.)

Other words in this last section of Isaiah also resonate strongly with texts in the New Testament. The ingathering of the outcasts (56:8) and the flocking of all the nations to Zion (60:1–18) together are reflected in the prediction of Jesus that “this good news of the kingdom will be proclaimed throughout the world, as a testimony to all the nations; and then the end will come” (Matt 24:14).

The statement that those coming from Sheba “shall bring gold and frankincense, and shall proclaim the praise of the Lord” (60:6) most likely informed the story that Matthew created, concerning the wise ones from the east who came to see the infant Jesus and “offered him gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh” (Matt 2:11).

******

Further oracles set out exactly what the justice that God desires (56:1; 61:8) looks like. The extensive worship of idols (57:1–13) will bring God’s wrath on the people; “there is no peace, says my God, for the wicked” (57:13). Rather, “the high and lofty one who inhabits eternity, whose name is Holy” chooses “to revive the spirit of the humble and to revive the heart of the contrite” (57:15).

Because God indicates that “I will not continually accuse, nor will I always be angry” (57:16), the prophet conveys what the Lord sees as the fast that is required; not a fast when “you serve your own interest on your fast day,

and oppress all your workers” (58:3), but rather, a fast “to loose the bonds of injustice, to undo the thongs of the yoke, to let the oppressed go free,

and to break every yoke … to share your bread with the hungry, and bring the homeless poor into your house; when you see the naked, to cover them, and not to hide yourself from your own kin” (58:6–7). These words resonate with the actions of “the righteous” in the well-known parable of Jesus, as they gave food, water, a welcome, clothing, and care to those sick or imprisoned (Matt 25:31–46).

The prophet laments that “there is no justice … justice is far from us … we wait for justice, but there is none … justice is turned back … the Lord saw it, and it displeased him” (59:8–15); he declares that, as a consequence, God “put on righteousness like a breastplate, and a helmet of salvation on his head; he put on garments of vengeance for clothing, and wrapped himself in fury as in a mantle” (59:17)—a description that underlines the later exhortations to the followers of Jesus to “put on the whole armour of God, so that you may be able to stand against the wiles of the devil” (Eph 6:10–17).

Because the Lord “loves justice” (61:8), the prophet has been anointed “to bring good news to the oppressed, to bind up the brokenhearted, to proclaim liberty to the captives, and release to the prisoners; to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favour, and the day of vengeance of our God” (61:1–2)—words which are appropriated by Jesus when he visits his hometown and reads from the scroll of Isaiah (Luke 4:18–19); “today this scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing”, Jesus declares (Luke 4:21).

Adhering to this way of justice, practising the fast that the Lord desires, means that he will give Israel a new name: “you shall no more be termed Forsaken, and your land shall no more be termed Desolate; but you shall be called My Delight Is in Her, and your land Married; for the Lord delights in you, and your land shall be married” (Isa 62:4). We have already seen the symbolic significance of names in considering the prophet Hosea and in Isaiah 8.

By contrast, vengeance will be the experience of Edom; using the image of trampling down the grapes in the wine press, the prophet reports the intention of God: “I trampled down peoples in my anger, I crushed them in my wrath, and I poured out their lifeblood on the earth” (63:1–6). So vigorously does God undertake this task, that he is attired in “garments stained crimson” because “their juice spattered on my garments and stained all my robes” (63:1–3). Once again, the prophet speaks in graphic terms about the consequences of sinfulness.

Confronted with this display of wrath and vengeance, the prophet adopts an attitude of penitence, yearning for God to “look down from heaven and see, from your holy and glorious habitation” (63:15). His plea for the Lord to “tear open the heavens and come down, so that the mountains would quake at your presence—to make your name known to your adversaries, so that the nations might tremble at your presence!” (64:1–2) must surely have been in the mind of the evangelists as the reported the baptism of Jesus, when he “saw the heavens torn apart and the Spirit descending like a dove on him” (Mark 1:10).

The book ends with a sequence in which the prophet reports the words of the Lord which indicate that Israel will be restored (65:1–16), followed by the statement that the Lord is “about to create new heavens and a new earth” (65:17–25; 66:22–23). (This passage appears in the lectionary on the 23rd Sunday flyer Pentecost.)

This vision is taken up and expanded in the closing chapters of the final book of the New Testament (Rev 21:1–22:7). The closing vision of Trito-Isaiah incorporates a number of references to earlier prophetic words: building houses and planting vineyards (65:21) recalls the words of Jeremiah (Jer 29:5–7); the image of wolves lying with lambs and lions “eating straw like the ox” recalls the vision of Isaiah (Isa 11:6–7).

The promise that “they shall not hurt or destroy all on my holy mountain” (65:25) recalls that same vision of Isaiah (Isa 11:9), whilst the next promise about not labouring in vain nor bearing children for calamity (65:23) reverses the curse of Gen 3:16–19. The story of creation from the beginning of Genesis is evoked when the Lord asserts that “heaven is my throne and the earth is my footstool … all these things my hand has made” (66:1–2); these are the words which Stephen will quote back to the council in Jerusalem (Acts 7:48–50) and will lead to his death at their hands.

Even to the very end of this book, the judgement of the Lord is evident; the prophet declares that “the Lord will come in fire, and his chariots like the whirlwind, to pay back his anger in fury, and his rebuke in flames of fire; for by fire will the Lord execute judgment, and by his sword, on all flesh; and those slain by the Lord shall be many” (66:15–16).

Nevertheless, the glory of the Lord shall be declared “among the nations” (66:19) and “they shall bring all your kindred from all the nations as an offering to the Lord” (66:20). The universalising inclusivism that was sounded at the start of this prophet’s work is maintained through into this closing oracle. In “the new heavens and the new earth which I will make … all flesh shall come to worship before me, says the Lord” (66:22–23). The vision lives strong!

*****

See also