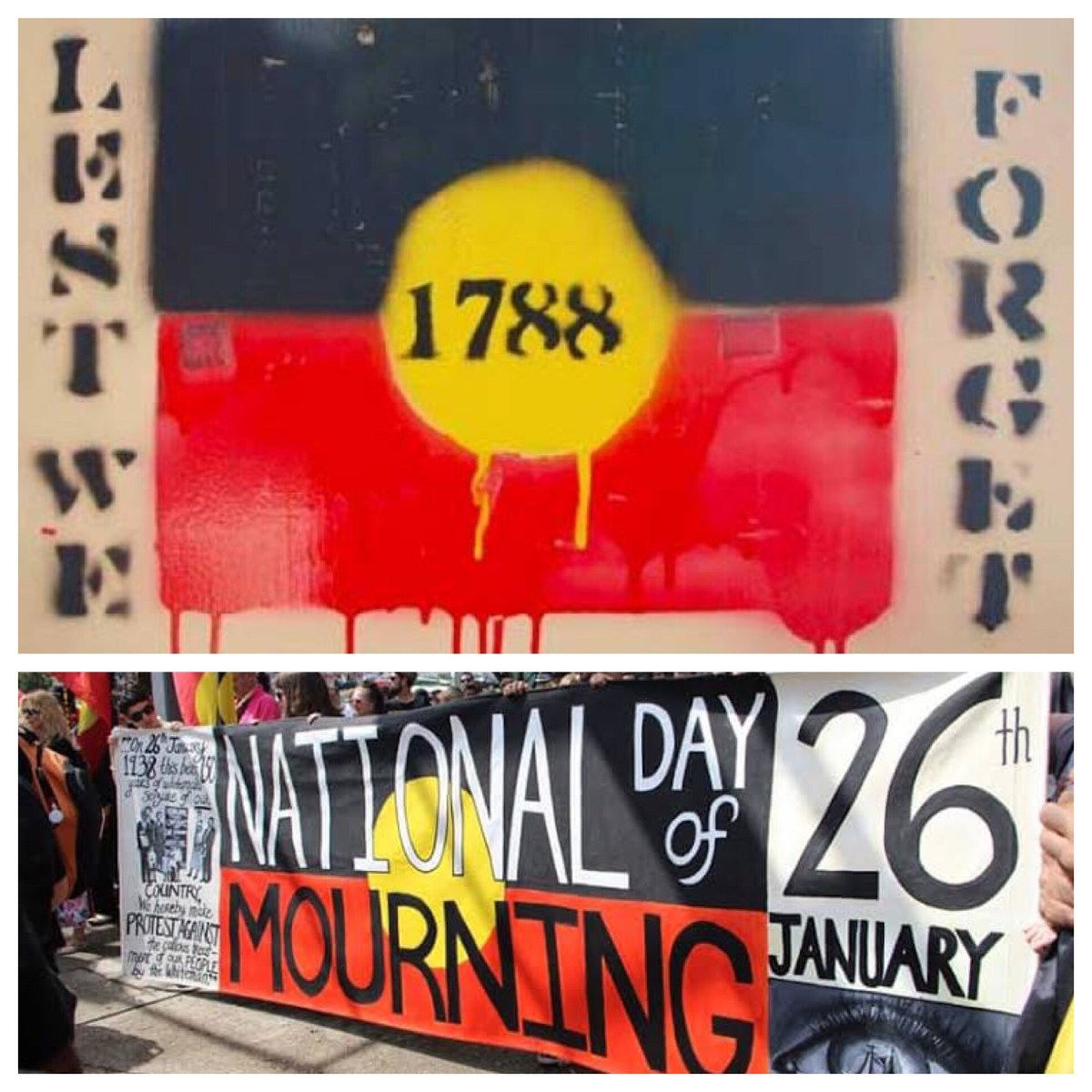

During this National Reconciliation Week, I think it is worth recalling the evidence for various positive and respectful relationships that existed between First Peoples and the invading colonisers from Britain. We are accustomed, now, to reading of the violent conflicts and massacres that occurred. These are tragic parts of our history that we must not deny, overlook, or ignore.

But in the early stages of the colony—and, indeed, stretching throughout the colonial period—there were mutually respectful relationships between these groups. National Reconciliation Week seems to be a good time to recall this.

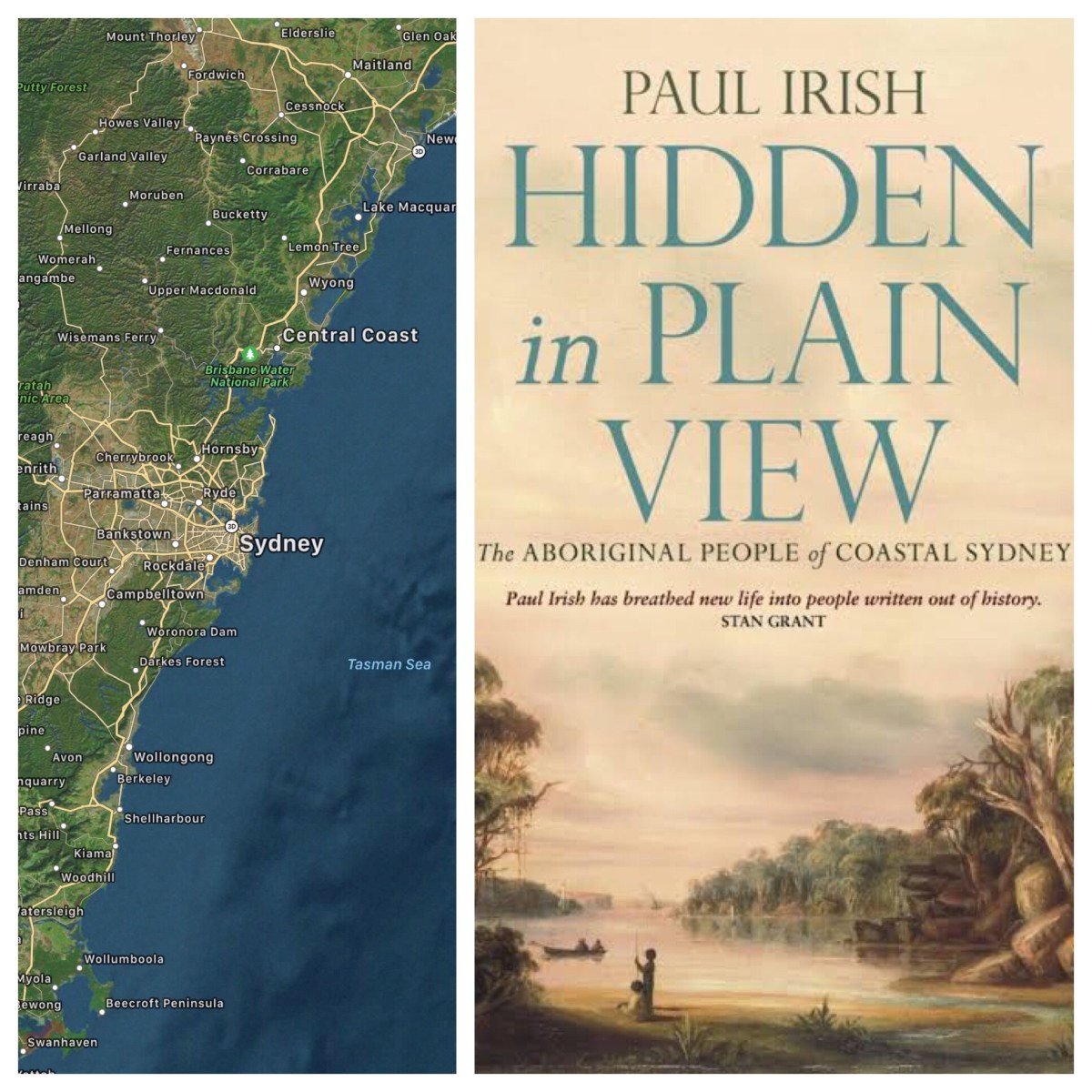

Perhaps the best known persona from amongst the First Peoples encountered by the invading British coloniser was Bennelong, born in 1764 on the southern shore of the Parramatta River. Paul Irish (in Hidden in Plain View) notes that his various family connections meant that Bennelong had connections to country on Goat Island, at Botany Bay, on the lower north shore of Sydney Harbour, and along the northern side of Parramatta River.

Bennelong was kidnapped in November 1789, under the orders of Governor Arthur Phillip, who thereby set an unfortunate tone for the relationship with the locals from the very early years of the colony. Phillip apparently assumed that Bennelong was a “King” of the local people, and thus the correct person with whom to negotiate about co-existing in the same area. It was an attempt to build a constructive relationship, even if it was carried out in what we now recognise to be an entirely flawed manner.

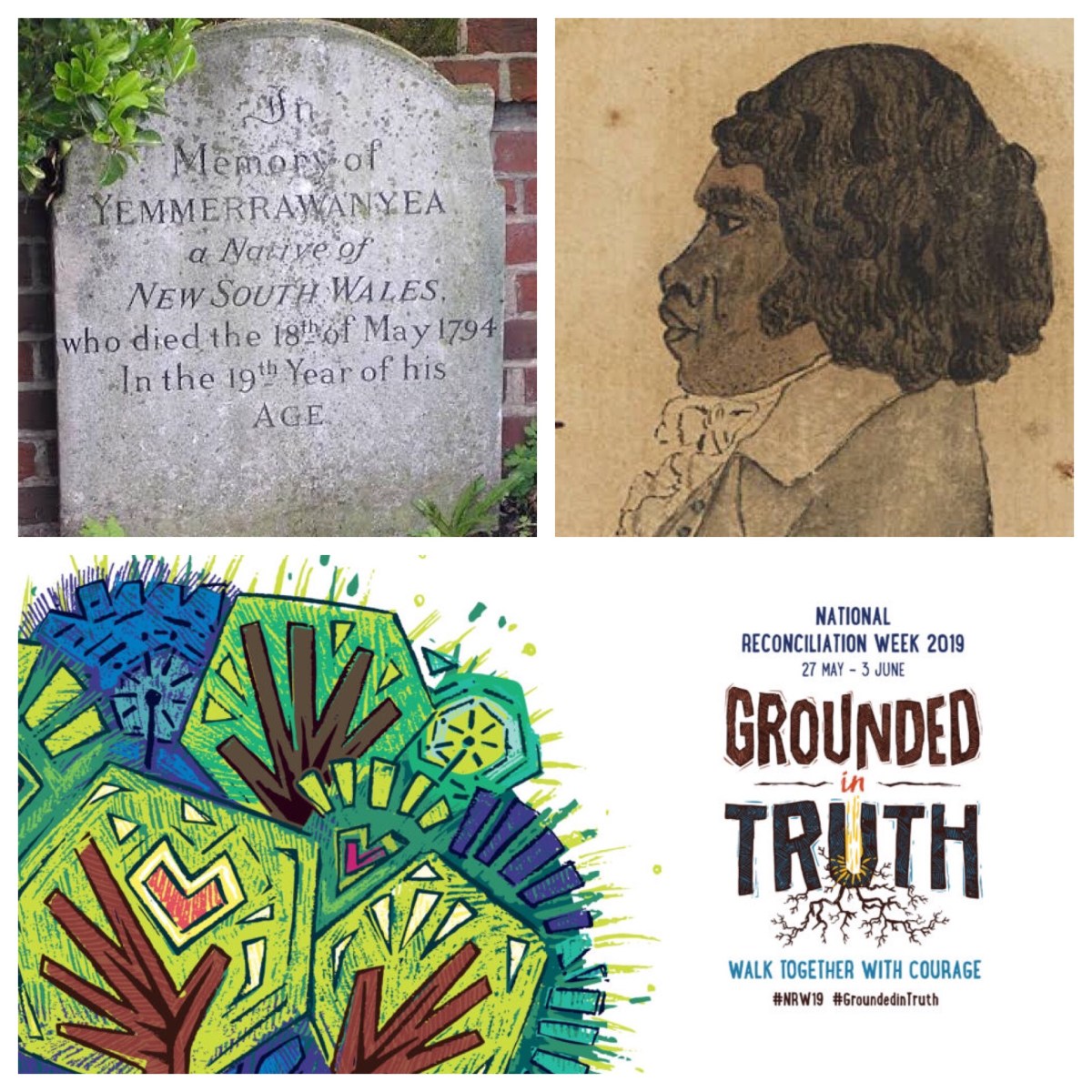

It is said that Bennelong took readily to life among the white men, relished their food, acquired a taste for liquor, learned to speak English and became particularly attached to the Governor. At the end of his term as Governor in 1792, Arthur Phillip travelled to England with Bennelong and another Aborigine, Yemmerrawanne, a Wangal man of the Eora people.

Yemmerrawanne was described by Watkin Tench, in his work, A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson (1793), as a “good-tempered lively lad” who became “a great favourite with us, and almost constantly lived at the governor’s house”. (See https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/yemmerrawanne)

Yemmerrawanne never returned home from his trip to England. After a long illness, he died from a lung infection on 18 May 1794 at the home of Mr Edward Kent at South End, Eltham in the county of Kent. His gravestone in Kent marks his life, and death.

Bennelong stayed in England from 1792 to 1795. On his return to Sydney, he was able to develop more positive relationships with the British, and functioned as an advisor to Governor Hunter.

Bennelong lived his last years with one of his wives, Boorong, at Kissing Point, with an extended group of about 100 people, until his death on 3 January 1813. He was buried in the Kissing Point orchard of the brewer James Squire—no relationship! Squire had been a great friend to Bennelong and his clan; another sign of positive, respectful relationships between Aborigines and the colonisers. We need to learn from such stories in our history.

See the extensive article on Bennelong in the Australian Dictionary of Biography at http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/bennelong-1769

The image portrays Bennelong, the grave of Yemmerrawanne, and the 2019 National Reconciliation Week logo and theme.

See also

https://johntsquires.com/2019/05/27/we-are-sorry-we-recognise-your-rights-we-seek-to-be-reconciled/

https://johntsquires.com/2019/05/28/reconciliation-on-the-land-of-australia-learning-from-the-past/

On the doctrine of discovery: https://johntsquires.com/2018/08/13/affirming-the-sovereignty-of-first-peoples-undoing-the-doctrine-of-discovery/

![“Resembling the park lands [of a] gentleman’s residence in England”](https://johntsquires.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/img_0170.jpg?w=1200)