“If any of you lacks wisdom, let him ask God, who gives generously to all without reproach, and it will be given him”. So we read at the start of the treatise of James (1:5). There is a strong wisdom flavour to this treatise. The word appears in just four verses (1:5; 3:13, 15, 17), but the nature of the book is quite akin to the most famous work of wisdom in scripture: the book of Proverbs.

The “letter” of James is, in reality, a moral treatise (see https://johntsquires.com/2021/08/25/on-care-for-orphans-and-widows-james-1-pentecost-14b/) Sometimes called “the Proverbs of the New Testament,” the book of James provides practical guidance on how to live. It canvasses matters such as perseverance, controlling one’s tongue when speaking, submitting to God’s will, responsibilities towards the poor, dealing with anger, and fostering patience.

In terms of its style, James reflects the wisdom tradition that is so evident in Hebrew Scripture and in continuing Jewish traditions. An important place was ascribed to Wisdom amongst Jews of the Dispersion; Wisdom became a key figure for such Jews, as is reflected in a number of writings.

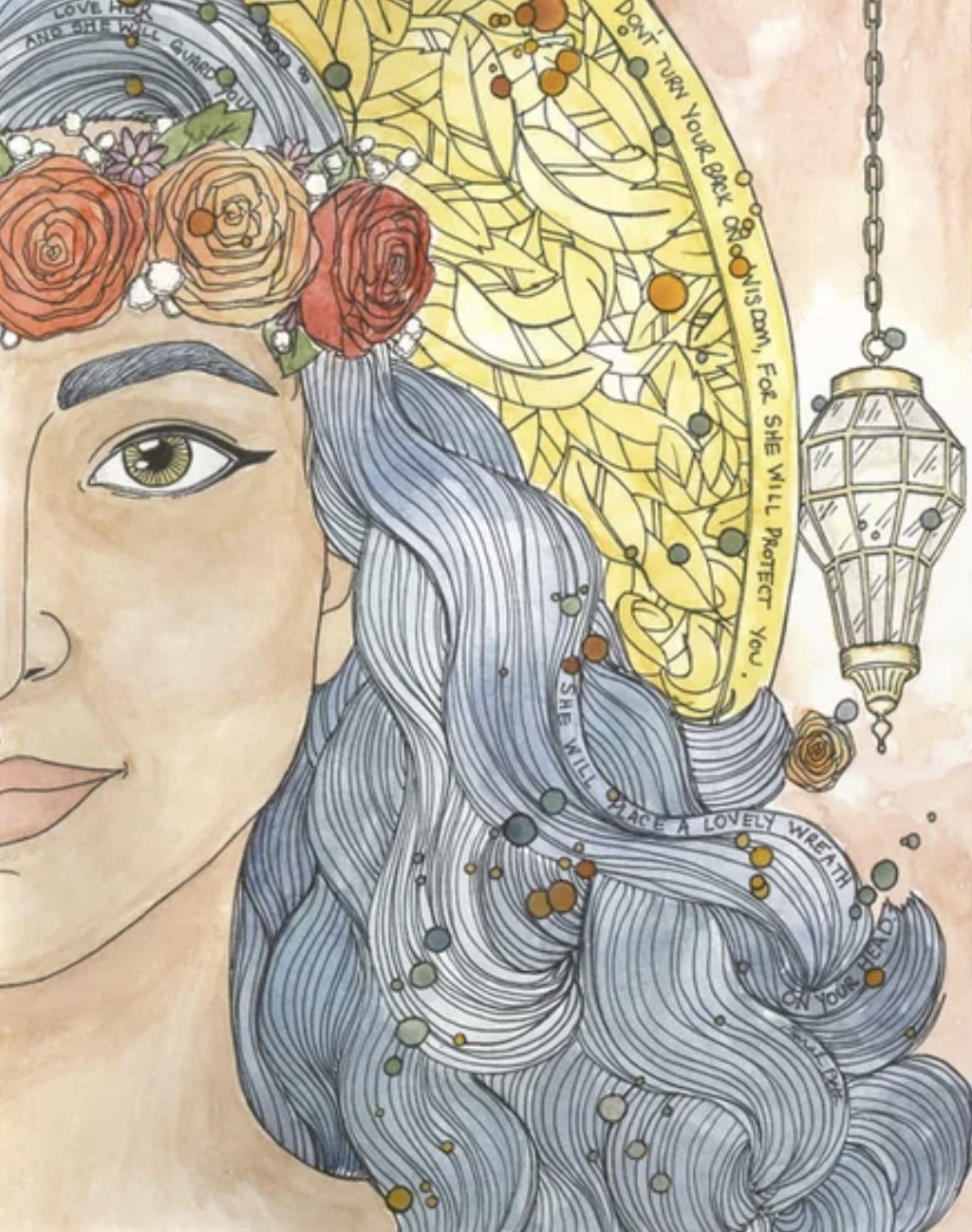

Wisdom is highlighted in Proverbs, which affirms that Wisdom was present with God at creation (Prov 8:22–31). Wisdom was the key creative force at work beside God, in conjunction with God, in creation the world. Wisdom plays a key role in the book of Sirach, where she gives knowledge, makes demands of those seeking instruction from her, imposes her yoke and fetters on her students, and then offers rest (Sir 6:24–28; 51:23–26). Furthermore, Wisdom is portrayed as the intermediary assisting God at creation and throughout salvation history (Sir 24:1–8).

Another document which highlights the role of Wisdom, is the work known as the Wisdom of Solomon—a work which the anonymous author tells of his own search for Wisdom. But the description of Wisdom that is given in this book is more philosophical than biblical; it owes much to the developing middle platonic philosophy of the late Hellenistic period. Wisdom is described as “a breath of the power of God, a pure emanation of the Almighty” (Wis Sol 7:25) and reflects a most dazzling sequence of attributes (Wis Sol 7:22–24).

A comparison with Proverbs and Sirach can be drawn with Matthew, where it is said that Wisdom is at work in Jesus; when the Son of Man eats and drinks with tax collectors and sinners, Jesus declares that “Wisdom is justified by her deeds” (Matt 11:19b). Soon after those words, the Matthean Jesus explicitly adopts the language of Wisdom in a well-known set of words. Like Wisdom, he is a teacher (Matt 11:27). Like Wisdom, he invites his followers to take on the yoke of learning, and through this, find true rest (Matt 11:28–30).

Jesus teaches extensively in the style of the wise teacher, employing strings of short, pithy epithets and succinct maxims (see, for example, the collation of such sayings at Matt 6:19–34; 7:1–27; 9:10–17; 10:24–42; 18:1–14).

*****

The divine gift of wisdom occupies a central position in the treatise of James (1:5–8); this “wisdom from above” is to be contrasted with wisdom which is “earthly, unspiritual, devilish” (3:13–18).

Numerous epithets typical of the wisdom style are included in the treatise; there are succinct sayings which provide a definitive conclusion to discussion of a topic; for example, “mercy triumphs over judgement” (2:13; compare Matt 9:13) or “who are you to judge your neighbour?” (4:12; compare Matt 7:1).

Practical guidance, which also features in wisdom literature, runs through the treatise of James: “do not be deceived” (1:16), “care for orphans and widows” (1:27), do not favour the rich over the poor (2:1–7), curb your tongues, like putting a bridle in a horse’s mouth (3:3), “do not be boastful” (3:14), “humble yourselves before the Lord” (4:10), “do not grumble against one another” (5:9), “do not swear…by any oath” (5:12), “pray for one another” (5:16).

The treatise of James includes a biting tirade against the oppressive actions of the rich (5:1–6). James quotes snippets of pertinent prophetic denunciations of the rich (Isa 5:9; Jer 12:3), yet the same perspective is evident in Wisdom Literature. We see this, for example, in: “riches do not profit in the day of wrath, but righteousness delivers from death” (Prov 11:4); “a good name is to be chosen rather than great riches, and favour is better than silver or gold” (Prov 22:1); “whoever oppresses the poor to increase his own wealth, or gives to the rich, will only come to poverty” (Prov 22:16).

In an extended diatribe against wealth and honour (Eccles 5:8–6:12), The Teacher notes, “He who loves money will not be satisfied with money, nor he who loves wealth with his income; this also is vanity.” (Eccles 5:10). In Job, Zophar the Naamathite speaks of the wicked: “He swallows down riches and vomits them up again; God casts them out of his belly” (Job 20:15). Antagonism to the rich accumulating more and more wealth is found in various Wisdom works.

A diatribe against engaging in various prohibited actions (arguing, coveting, murder, adultery and impurity, 4:1–10) includes the statement, “God opposes the proud but gives grace to the humble” (James 4:6), which is perhaps citing Prov 3:34, “toward the scorners he is scornful, but to the humble he gives favour”.

The treatise as a whole ends with another saying which includes words from Proverbs: “if anyone among you wanders from the truth and someone brings him back, let him know that whoever brings back a sinner from his wandering will save his soul from death and will cover a multitude of sins” (5:20), citing the later part of Prov 10:12, “hatred stirs up strife, but love covers all offenses”.

The numerous scriptural allusions peppered through the moral exhortations of each chapter certainly demonstrate that the influence of Hebrew scripture on this book, and particularly of the Wisdom literature, cannot be underplayed.

*****

See also https://johntsquires.com/2021/09/12/in-the-squares-she-raises-her-voice-lady-wisdom-in-proverbs-pentecost-16b/ and https://johntsquires.com/2021/09/08/wisdom-cries-in-the-streets-proverbs-1-pentecost-16b/

and there’s a fine sermon on this passage by Avril Hannah-Jones at https://revdocgeek.com/2021/09/18/sermon-avril-preaches-to-herself/