“Bless our God, O peoples, let the sound of his praise be heard” (v.8). That’s the opening line of the section of Psalm 66 which offered by the lectionary for this coming Sunday, the Sixth Sunday in Easter (Ps 66:8–20). In these words, the call is made for people to bless and praise God because he is the one “who has kept us among the living” (v.9). This makes this psalm a most suitable song for the season of Easter, when the church celebrates the new life offered to believers through the resurrection of Jesus from the dead.

Blessing God is a favourite Jewish activity—indeed, so many prayers still used by Jews today begin with a phrase of blessing: “Blessed are you, O Lord our God …”. Blessed are You, O Lord our God, Ruler of the universe, Who brings forth bread from the earth is prayed before a meal. Blessed are You, o Lord our God, Ruler of the universe, who creates the fruit of the vine is prayed before drinking wine.

And a favourite blessing which I learnt from Jews is Blessed are you, O Lord our God, Ruler of the Universe, who has kept us alive, sustained us, and brought us to this moment. It’s a prayer to mark momentous occasions in life. All of these prayers of blessing begin with the Hebrew words, Baruch atah Adonai Elohenu melekh ha’olam, the same formula of approaching, acknowledging, and blessing God.

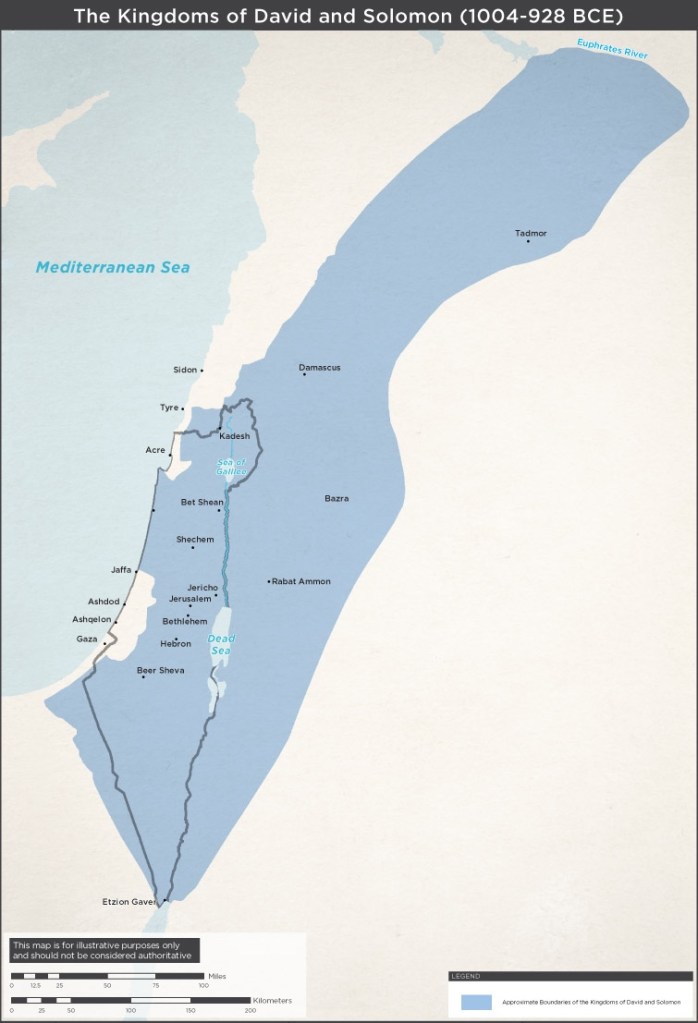

We can see that formula used in blessings spoken by David, who exhorts the people to “bless the Lord your God” (1 Chron 29:19), and the psalmist, who prays, “Blessed are you, O Lord; teach me your statutes” (Ps 119:12), as well as in later Jewish texts such as Tobit 3:11; 8:5, 15–17; Judith 13:17; 14:7; the Prayer of Azariah (six times), and 1 Maccabees 4:20. It appears also in New Testament texts such as Luke 1:68; Rom 9:5; 2 Cor 1:3; Eph 1:3; and 1 Pet 1:3.

More familiar, perhaps, is when Jesus uses a prayer of blessing, but speaks it to human beings; “blessed are you, Simon son of Jonah” (Matt 16:17), or “blessed are the eyes that see what you see”, to his disciples (Luke 10:23), or “blessed are those who have not seen and yet have come to believe” (John 20:29), and most famously of all, in a set of blessings spoken to a crowd on a level place (Luke 6:20–22) or to his disciples on a mountain top (Matt 5:3–12). Jesus blessed people. But blessing God is something that is not unknown within Judaism.

The primary reason to bless God, then, is that we are “kept among the living” (v.9). What follows from that affirmation is the statement, “You, O God, have tested us; you have tried us as silver is tried” (v.10). We know that life entails testing; no human being has avoided those moments in their lives when trials and testings are presented, seeking to entice us to think or act in unhelpful ways.

Scripture reflects this reality, that life entails testing, at many places. The fundamental paradigm is set out in the paradigmatic story of Abraham and Isaac (Gen 22:1–19), and then in narratives about Joseph (Ps 105:16–19), the years when the people wandered in the wilderness (Deut 8:2), the incident at Rephidim (Exod 17:1–7; Deut 6:16; 33:8; Ps 81:7), and then whilst the people were living alongside hostile nations when in the land (Judg 3:1–6). And, of course, there is the similar paradigmatic testing story in the life of Jesus (Mark 1:12-13 and parallels).

The Psalmist notes that “the Lord tests the righteous and the wicked” (Ps 11:5) and the prophet declares the word of the Lord, that “I have refined you, but not like silver; I have tested you in the furnace of adversity” (Isa 48:10; so also Zech 13:7–9). In the words of the sage, then, “I said in my heart with regard to human beings that God is testing them to show that they are but animals” (Eccles 3:18) and, using the same imagery as Ps 66, notes that “the crucible is for silver, and the furnace is for gold, but the Lord tests the heart” (Prov 17:3).

After listing various ways in which the people have been tested—“you brought us into the net; you laid burdens on our backs; you let people ride over our heads; we went through fire and through water” (vv.10–11), the psalmist declares, “you have brought us out to a spacious place” (v.12 in the NRSV translation), or “a place of great abundance” (in the NIV).

The unusual Hebrew word which is translated as “spacious place”, la-yerawah, appears also in Psalm 23 in the affirmation, “my cup overflows” (Ps 23:5); the root word, ravah, has a sense of saturation, abundance, or being filled to overflowing (according to the Brown—Driver—Briggs Lexicon). The end result of testing is a place of fulfilment and satisfaction.

In response, the psalmist states, “I will come into your house with burnt offerings; I will pay you my vows” (v.13). Prescriptions for burnt offerings, to be offered at the altar of burnt offerings (Deut 12:27; Exod 20:24), are detailed in Lev 1:1–17 and 6:8–13. They are integral to the rituals of the Temple and have a firm place in the piety of faithful people in ancient Israel.

Also integral to the temple liturgy are the vows which are to be paid to God. The psalmist elsewhere affirms, “I will pay my vows” (Ps 22:25; 50:14; 61:8; 65:1; 66:13; 76:11; 116:14, 18). The words of the psalmist are echoed by Eliphaz in one of his speeches to Job: “you will delight yourself in the Almighty, and lift up your face to God; you will pray to him, and he will hear you, and you will pay your vows” (Job 22:26–27).

So the psalm continues, “I will offer to you burnt offerings of fatlings, with the smoke of the sacrifice of rams; I will make an offering of bulls and goats” (v.15). This correlates with the levitical provisions, as already noted. The psalmists inevitably write from within the religious system of the time—which makes sense, since the psalms were composed for singing within the Temple liturgy.

This contrasts with many of the words of the prophets, who in a sense stand on the edge of the religious life of the nation, and offer their criticisms of the excesses and injustices that were part of life at that time (as, indeed, they continue to be, sadly, today). We might think, for instance, of how the prophets criticised the people for their offerings and sacrifices whilst tolerating such injustice in their communal life (Isa 1:11–14; Jer 6:20; Ezek 20:27–28; Hos 8:13; 9:4; Mal 1:14).

So the prophetic critique of Temple practices (which Jesus picks up at Matt 9:13; 12:7, quoting Hos 6:6) needs to be held in tension with the psalmists’ affirmations of those practices when they are performed faithfully. Although Jesus, following Hosea, appears to place mercy (hesed) in opposition to sacrifice, both mercy and sacrifice are integral to Israelite religion.

To end this song, the psalmist offers an exhortation followed by an affirmation. The exhortation is to “come and hear, all you who fear God, and I will tell what he has done for me” (v.16). “Those who fear God” is a typical characterisation of faithful people who trust in God and adhere to God’s ways of justice and righteousness, including Abraham (Gen 22:12), Joseph (Gen 42:18), leaders appointed by Moses (Exod 18:21), and indeed all who are faithful amongst the people (Lev 19:14, 32; 25:17, 36, 43; Deut 4:10; 6:2, 13, 24; etc; 1 Sam 12:14, 24; 1 Ki 8:40–43).

As Moses declares, “O Israel, what does the Lord your God require of you? Only to fear the Lord your God, to walk in all his ways, to love him, to serve the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul, and to keep the commandments of the Lord your God” (Deut 10:12).

“What God has done” is an occasional biblical phrase, appearing in assorted places (Num 23:23; Deut 3:21; Josh 23:3; Ps 64:9; Eccles 3:11; Jer 5:19; Dan 9:14). In the New Testament, it is picked up in what Jesus says to a healed demoniac (Luke 8:39) and then in writings of his disciples (Rom 3:24–26; 8:3; Acts 2:22, 36; 14:27; 15:12; 21:19; John 3:16–17). It affirms the continuing and ongoing actions of God—what a former generation of scholars called “salvation history”—which is known through the stories of Israel and then through the life of Jesus and his followers.

The affirmation which closes this psalm is offered in typical Hebraic style, with parallel phrases that repeat and develop the central idea. In verse 19, the first statement, “truly God has listened”, is mirrored in the next phrase, “he has given heed to the words of my prayer”. In verse 20, “he has not rejected my prayer” is then expressed in a varied manner in the closing phrase, “[he has not] removed his steadfast love (hesed) from me”.

From Exodus to Nehemiah, God’s steadfast love and faithfulness (hesed) is praised, in a refrain which recurs in many places (Exod 34:6; 2 Chron 30:8–9; Neh 9:17, 32; Jonah 4:2; Joel 2:13; Ps 86:15; 103:8, 11; 111:4; 145:8–9). Here, the psalmist uses this central insight into the nature of God to conclude the song, in which human trust in God and fidelity to God’s way have been well-expressed throughout.

The final words of the psalm form a blessing (linking back to verse 8) which emphasises the hesed of God (variously translated as mercy, or steadfast love). The psalm as a whole thus ties together the religious practices of the people (vows and sacrifices) and the understanding of God’s essential being (merciful and loving). It is a reminder that we need to hold the whole of the biblical witness together as revelatory of God; not select one aspect, not preference one over another, but hold all together. For in that, we draw near to the fullness of God.