During the long season of “ordinary time” After Pentecost, the lectionary offers stories of some quite extraordinary people, drawn from the sagas that tell of the key moments in the story of Israel. These sagas are found in the narrative books, Genesis, Exodus, Deuteronomy, Joshua, and Judges. These stories run through until the Twenty-Fifth Sunday after Pentecost, in mid-November.

This coming Sunday, we hear a well-known story relating to the patriarch and matriarch whose adventures comprises significant part of Genesis (12:1—25:11). The story tells of how Abraham and Sarah undertook the long journey from Ur to Canaan (12:1–9), spent time in Egypt (12:10–20) and the Negeb (13:1–14:24), entered into covenant with God (15:1–21) and sealed this with a ceremony of circumcision (17:1–27).

Abraham himself has also fathered a child with his servant, Hagar (16:1–16); that dimension of the story appears important as it signals that there would be a descendant of Abraham, to fulfil the promise made earlier (12:2; 15:12–21). Yet the child who arrives is the son of Hagar, not Sarah. So the passage which is offered by the lectionary for this coming Sunday (Gen 18:1–15) addresses the infertility of Abraham and Sarah, by telling of how this couple learnt that they would, indeed, become parents together.

Abraham was allegedly aged 100 years, while Sarah was aged 90 years (see 17:17). It is no wonder that Sarah, when she learns of her forthcoming pregnancy, laughs (18:12)—although when confronted about this, she denies having laughed (18:15). Yet the name of the son to be born to Sarah, Isaac, means “the one who laughs”. So the joke is on her!

In the next two weeks, the lectionary will offer stories from subsequent chapters of Genesis, that focus on the two sons of Abraham: first, Ishmael, banished to the desert by his father, where he and his mother were vulnerable (21:8–21); and then Isaac, called to his own sacrifice under the hand of his own father (22:1–14). Certainly, Abraham does not come out of either of these stories looking very good!

The news about Isaac comes to Sarah and Abraham after a visit from three men, one of whom looks forward to the birth of a son to Sarah (18:10). Abraham had welcomed the visitors, as was the custom, saying “let a little water be brought, and wash your feet, and rest yourselves under the tree; let me bring a little bread, that you may refresh yourselves” (18:4–5).

Quite tellingly—given the strongly patriarchal nature of ancient society—we next learn that “Abraham hastened into the tent to Sarah, and said, ‘Make ready quickly three measures of choice flour, knead it, and make cakes’”. There we have it: the man decides, the woman implements. Has this changed in today’s society? A little? A lot? The jury is still out …

But more than this; “Abraham ran to the herd, and took a calf, tender and good, and gave it to the servant, who hastened to prepare it” (18:7). The master selects the animal; the servant prepares the meal. Again, all in accord with the customs of the time. But the next verse has always jarred with me: “Then he took curds and milk and the calf that he had prepared, and set it before them” (18:8). The food that he had prepared??? The food that he had ordered others to prepare, surely!

In his commentary on this passage in With Love to the World, the Revd Dr John Jegasothy, a retired Uniting Church Minister who came to Australia some decades ago, seeking asylum from civil war in Sri Lanka, observes that “strangers and aliens were considered as enemies in the ancient times. We, today, warn our children not to talk to strangers, because they could be predators”. He notes that, in the experience of his own family, “we have met many strangers in our lives, like new neighbours or new migrants in this multicultural country, who have become friends and channels of blessings to us. We too have become good neighbours and friends to them.”

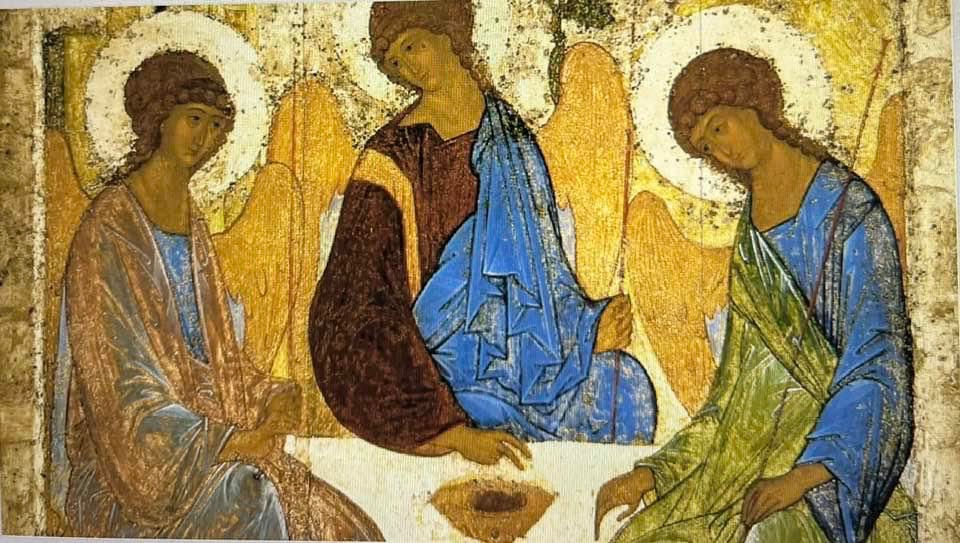

The visitors, offered hospitality by Sarah and Abraham, bring an important revelation to them. These three travellers are the means by which God speaks into the ongoing story. Later Christian interpreters have, unhelpfully and inaccurately, seen the “three men” as a visitation of the Triune God—an interpretation made famous through Andrew Rublev’s early 15th century icon (pictured).

The story, of course, is an ancient Jewish legend, which tells of hospitality and progeny; the Christian doctrine of the Trinity was shaped amidst the patriarchal polemics of the state-sponsored church of the later Roman Empire as church leaders argued about complex matters of speculative philosophical questions. (Was Jesus truly human? Was he truly divine? How are God and Jesus related? Do they share the same essence? Are they of like nature, or of exactly the same nature? and so on …)

The two are worlds apart. It’s another case where Christian interpreters, wanting to find “biblical proof” for that doctrine, have done great damage to a passage of Hebrew Scripture, forcing it to say something that clearly is not evident from a plain reading within the ancient Israelite context.

If we focus on the dynamic that is evident in the story, we see how it highlights the importance of hospitality. And that should encourage and inspire us, as we go about our daily lives, to offer that hospitality to others: to welcome the stranger, invite into our homes and our lives those in need of food, drink, and shelter; to reach out to those caught in the prisons of their minds, their poverty, their crimes, their inadequacies.

All of which sounds like sage words … now, where have we heard that before?

*****

See also