As we continue through the season After Pentecost, the lectionary offers stories of some quite extraordinary people, drawn from the sagas that tell of the key moments in the story of Israel. The sagas we will hear are found in the narrative books, Genesis, Exodus, Deuteronomy, Joshua, and Judges.

This coming Sunday, we hear another story relating to the patriarch of Israel, Abraham, his Egyptian slave Hagar, and the child that is born to them, Ishmael (21:8–21). This is the first child of Abraham; he and Sarah had not produced any children over many years. The fact that his mother is Abraham’s servant, Hagar, rather than his wife, Sarah, is not unusual. Later in the Genesis saga, Abraham’s grandson Jacob, already married to Leah and then to her sister Rachel, has children by Leah (29:32–35), as well as his servant Bilhah (30:1–7), and later by Leah’s servant Zilpah (30:9–11), before eventually Rachel gave him a son, Joseph (30:22–24) and later, Benjamin (35:16–21).

Earlier in Genesis, in a passage omitted by the lectionary, a report is provided of the circumstances leading to the birth of Ishmael (16:1–16). The naming of the child is announced by angelic visitation to Hagar (16:7–12), establishing a pattern which will later be used in recounting the naming of Samson (Judg 14:2–7), the child of a young woman in the time of Isaiah (Isa 7:13–16), and then of Jesus (Matt 1:20–21; Luke 1:31). It appears, at this earlier point, that it is Ishmael through whom the promise made to Abraham would be fulfilled: “I will make you exceedingly fruitful; and I will make nations of you, and kings shall come from you” (17:6).

In this week’s passage, however, the enmity that was evident once Sarah learnt that Hagar had conceived, comes to full fruition. Once the pregnant Hagar had this news confirmed, “she looked with contempt on her mistress” (16:4), and so “Sarah dealt harshly with her, and she [Hagar] ran away from her” (16:6). Hagar retreats to a spring in the wilderness (16:7), which is where the angel makes their announcement about the name and character of the child. Ishmael means “God has heard”, signalling that God was acting to fulfil the promise. But the life foreseen for Ishmael was one of conflict and opposition: “he shall live at odds with his kin” (16:12).

Hagar presumably returned to be with Abraham and Sarah; in due time, a son, Isaac, is born to Abraham and Sarah (21:1–7). At the start of this week’s passage (21:8–21), it appears that Ishmael is playing happily with his brother (21:8). Jewish interpreters note that the Hebrew word used, tsachaq, can be interpreted as “playing” or “laughing”—or with a more menacing overtone, perhaps hinting at Ishmael’s envy of his half-brother as the favoured one, at least in Sarah’s eyes.

(The LXX, in translating this word into Greek, takes the more benign option, adding the words “with his brother” to imply that this is just children playing games; and that is what Christian translators reflect in their translations.)

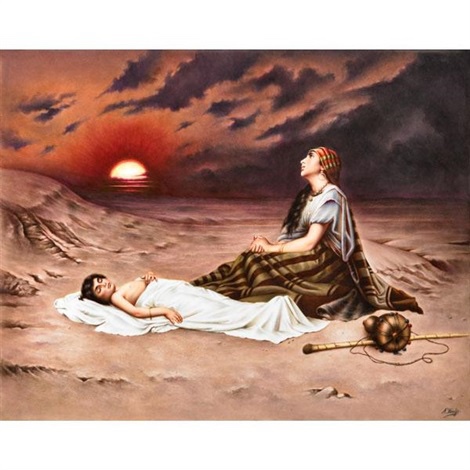

Sarah’s dissatisfaction with this moment of “play”—whether innocent or, perhaps more likely, with a threatening element—leads her to expel Hagar for another time, this time into the wilderness of Beersheba (21:9–14). Hagar’s distress is intense, such that she prepares for the death of the child Ishmael—only to be visited by another angelic intervention, inviting her to “lift up the boy and hold him fast with your hand”, assuring her that “I will make a great nation of him” (21:18).

Writing on the story in this week’s issue of With Love to the World, the Revd Sophia Lizares, a Uniting Church Minister originally from the Philippines, now serving in Perth, WA, says: “God is in the wilderness and hears even the least of the least. In times of trial, God opens our eyes to the goodness close at hand. Even those who have been banished, God accompanies into a unique and unexpected future. In God, the wilderness becomes a sanctuary where Hagar and Ishmael flourish.”

The story is told as an offering of hope—hope that what is yearned for will come to pass, even in the midst of distressingly difficult circumstances. The story has “a happy ending”, of sorts, for an angel intervenes (21:17)—does this perhaps indicate that Sarah was wrong to expel Hagar?

Guided by the angel, Hagar finds water (21:19) and the boy grows to become “an expert with the bow” (21:20). It is even said of him that “God was with the boy” (21:20), a presaging of what was later said of King Solomon (1 Chron 1:1), then later still of the infant Jesus, “the favour of God was upon him” (Luke 2:40), and of the whole life of Jesus, “God was with him” (Acts 10:38).

And the boy Ishmael does indeed become the father of “a great nation” (2:18)—through the 12 sons which he fathered! All’s well that ends well, it would seem.

*****

Yet the conflict that was to be visited upon Ishmael is an important element in this story which we must not pass by. “He shall be a wild ass of a man, with his hand against everyone, and everyone’s hand against him; and he shall live at odds with all his kin” (16:21) is a heavy burden to be laying on the child from the start of his life.

Although Ishmael was circumcised in accordance with the covenant that Abraham had entered into with the Lord God (17:23–27), and although he is indeed “blessed and made fruitful” (17:20) and does become the father of twelve sons (25:13–16) as well as a daughter (28:9), he still faced enmity. He bequeathed that conflicted state to his progeny. Indeed, the story of Ishmael functions (as do many of the stories in Genesis) as an aetiology.

An aetiology, as I have noted previously, tells of something that is said to have occurred long back in the past, but the focus is on present experiences and realities, for “such explanations elucidate something known in the contemporary world by reference to an event in the mythical past”.

In the developing Jewish tradition, Ishmael attracts negative stories. It is said that he prayed to idols—some rabbis offer this as the explanation for Sarah expelling Ishmael and Hagar into the wilderness. Other rabbis claim that Hagar, an Egyptian woman (16:1) was not “a slave girl” but rather a daughter of Pharaoh.

Some interpreters, following the opening given by the ambiguity in the Masoretic (Hebrew) text, interpret the “playing with Isaac” (21:9) as an attempt to usurp the birthright of Isaac, the son of Abraham’s wife. Was Ishmael play-acting how he planned to dispose of his half-brother, and claim the heritage of his father Abraham?

By contrast, Ishmael is honoured in Islam as a prophet and as the patriarch of Muslims. Abraham—Ibrahim in Arabic—is acknowledged as a messenger of God and recognised as father of the nations, as scripture attests. The Kaaba in Mecca, the holy site to which Muslims make pilgrimage each year, is considered to have been built by Abraham and Ishmael, while the near-sacrifice of Isaac, told in Gen 22, is commemorated by Muslims on the holy day of ‘Eid al-Ada (“the Feast of Sacrifice”). In Muslim thinking, Abraham cleansed the world of idolatry.

In the Muslim holy text, the Quran, there are a number of mentions of Ishmael, who is described as “an Apostle, a Prophet” (19:54), as “truly good”, along with Elijah (38:48), and as inspired, along with “Abraham … and Isaac, and Jacob, and their descendants, including Jesus and Job, and Jonah, and Aaron, and Solomon … and David” (4:163). He occupies a key place in the stories of their past.

*****

The Quran is well-disposed towards Isaac, declaring, “we believe in God, and in that which has been bestowed upon Abraham and Ishmael and Isaac and Jacob and their descendants, and that which has been vouchsafed by their Sustainer unto Moses and Jesus and all the [other] prophets: we make no distinction between any of them; and unto him do we surrender ourselves” (3:84; the term Islam, of course, means “surrender” or “submission”).

Antagonism between Jews and Muslims has nevertheless been experienced throughout much of the time which followed the establishment of Islam as a faith with its own doctrines and practices during the seventh century. Early Muslim expansionary undertakings brought cultural, technological, and literary developments through Persia, Syria, Arabia, Palestine, Egypt, and North Africa. There was a “golden age” under this Islamic rule, during which Jews, Christians, and Muslims lived together in harmony—the so-called convivienca.

During the Middle Ages, the Crusades undertaken under the auspices of the Roman Church scarred relationships between Christianity and Islam—the storming of Jerusalem in 1099 saw masses of Muslims slaughtered. Jerusalem was recaptured by Saladin in 1187, but he ordered that Christians not be slaughtered; Muslims controlled the city but allowed Christian pilgrims access to holy sites.

The Fall of Constantinople, capital of the Byzantine Christian empire, in 1453 and the later expulsion of Muslims from Spain marked the end of congenial relationships. Later Christian missionary enterprises regarded Indigenous and Muslim peoples as primitive and uncivilised, and forced a Western way of life onto them, creating a heritage that still plays out across the world today.

*****

In like manner, Jews living in Muslim lands throughout the Middle Ages were permitted to practise their faith and culture for many centuries, although there are various instances of localised massacres and ghettoisation of Jews by Muslims. The height of tension between these two faiths has been in the modern era, relating to the creation of the State of Israel.

In the 19th century, Zionist Jews were calling for Jews to return to their ancestral homeland, which had been under Muslim control for centuries. The declaration of the State of Israel in 1958, so soon after the Shoah (“the Destruction”) that Jews had so recently experienced in Nazi Germany, meant that Palestinians experienced the Nakba (“the Catastrophe”) of becoming displaced from a land that had been their home for many centuries.

Tensions about the borders of Israel, the rights of Jewish settlers, the removal of Palestinian (Muslim) residents, the barricading of the West Bank and the Golan Heights, as well as the Temple Mount in the centre of Jerusalem, have been the focus of increasing and apparently unresolvable tensions for the past 75 years. The Temple Mount—the place from which Abraham ascended into heaven, in Muslim belief—is also,contentious. This is where the Muslim Dome of the Rock is built, on the foundations which centuries ago formed the base of the two Jewish Temples (one built by Solomon, and then the second built under Nehemiah and extended by Herod the Great).

So the Ishmael story has been a potent saga throughout history, and stands today as a powerful signal of the possibility of co-operative relationships, but the unfortunate reality is one of fractured and unhappy relationships which have spilled out into aggressive and destructive conflict.

Might it be that as we hear again this story of Ishmael, Hagar, and Sarah, we might recommit to being makers of peace, and work towards the goal of co-operative harmony, so that “the wilderness becomes a sanctuary where Hagar and Ishmael flourish”, where Jews and Muslims and Christians can find a common, irenic venture?

May it be so.