We know that “she laughed”. And that she produced a miracle baby at the ripe old age of 90 (or so it is said). But what else do we know about Sarah? Before she disappears from view in the Hebrew Scripture passages that the lectionary is offering us, let’s spend some time thinking about Sarah.

During this season after Pentecost, the lectionary has been offering us stories selected from the ancestral sagas of Israel, tracing the way that the promise to Abraham—“I will make of you a great nation” (Gen 12:1), “look toward heaven and count the stars … so shall your descendants be” (Gen 15:5)—was able to come to fruition.

Over successive Sundays, we have read of the call to Abram (ch.12), the promise of a child to Sarah (ch.18), the banishment of Abraham’s son through his slave girl Hagar (ch.21), the near-sacrifice of the preferred son, Isaac (ch.22), and the manoeuvring by Abraham to ensure a wife for Isaac who is of “my country and my kindred” (ch.24).

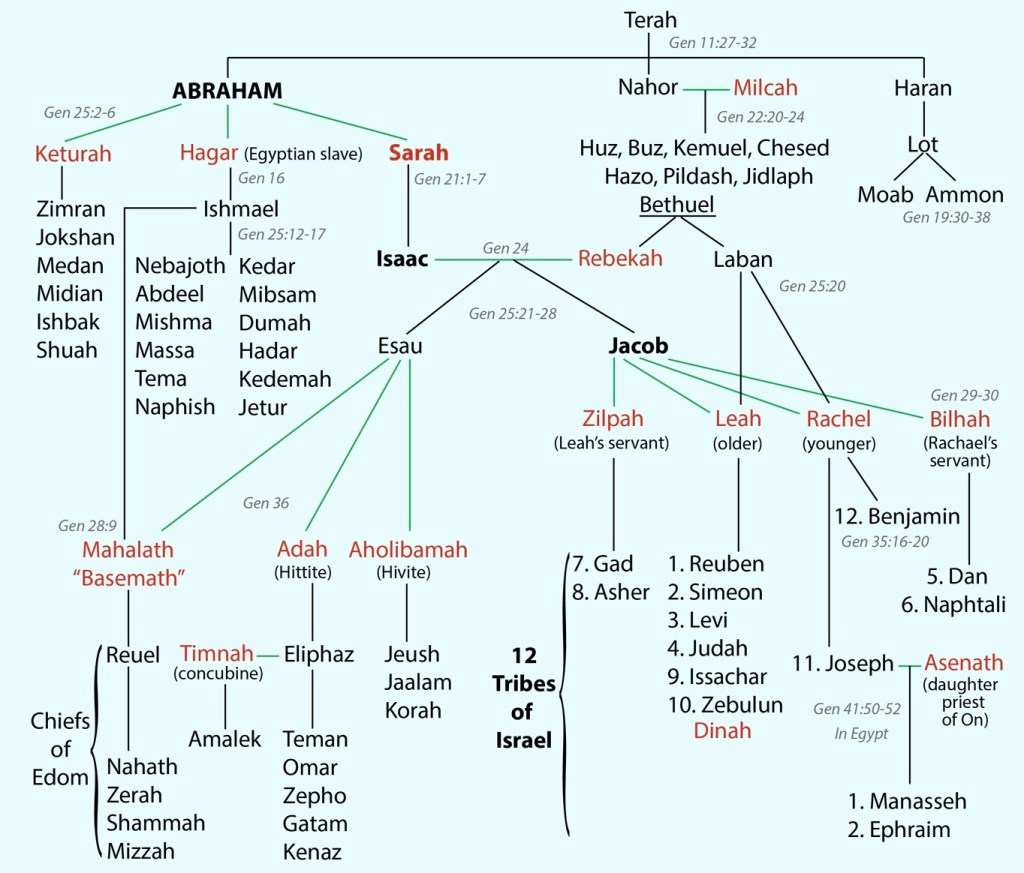

In future Sundays, we move on to stories about the twin boys born to Isaac and his wife Rebekah (ch.25), Jacob’s dream at the Jabbok (ch.28), Jacob and his marriages to, first Leah, and then Rachel (ch.29), and then the story of Jacob at Penuel, which explains how he had his name changed to Israel (ch.32). The story then focusses on one of Jacob’s twelve sons, Joseph, who is taken to Egypt (ch.37) and later saves his brothers during a famine (ch.45).

These stories—have you noticed?—follow the male line of descent, and place the male at the centre of the story. It is Abram’s call, Abraham’s near-sacrifice of Isaac, Isaac who needs a wife, Jacob who has a dream, Jacob who obtains two wives, Jacob who wrestled with God, and Joseph who becomes the saviour of his brothers.

What role is played by the women in the story? We do know the names of the matriarchs—Sarah, Rebekah, Leah and Rachel—and they do figure in the stories; but the focus is quite patriarchal, as would befit the nature of ancient society.

Sarah, whom we meet initially as Sarai (11:29), is essential to the storyline at various points; and she has come to be venerated alongside Abraham in later traditions. Paul refers to her as the means by which God’s promise is fulfilled (Rom 9:9) and he even offers her and Hagar together as providing an allegory for “the present Jerusalem, in slavery … and the Jerusalem above [who is] free, our mother” (Gal 4:21–26).

In the letter to the Hebrews, Sarah is named (in contrast to many other women) and takes her place alongside Abraham as part of “so great a cloud of witnesses” (Heb 12:1)—although all that is said of her is the stark declaration, “Sarah herself was barren” (Heb 11:11). The miracle, it would seem, was that “from one person, and this one as good as dead, descendants were born” (Heb 11:12)—that is to say, it was the transformation of the “as good as dead Abraham” that is being celebrated here.

In 1 Peter, Sarah is put forward as one of the “holy women who hoped in God”—although, in this instance, what is said of her again mirrors the patriarchal dominance of society; “Sarah obeyed Abraham and called him lord. You have become her daughters as long as you do what is good and never let fears alarm you” (1 Pet 3:5–6).

It takes an exilic prophet, whose words were appended to the earlier scroll of Isaiah, to give Sarah (almost) equal billing with Abraham: “Listen to me, you that pursue righteousness, you that seek the Lord. Look to the rock from which you were hewn, and to the quarry from which you were dug. Look to Abraham your father and to Sarah who bore you; for he was but one when I called him, but I blessed him and made him many.” (Isa 51:1–2).

So, what do we know of Sarah from those ancestral narratives which were told by word of mouth, handed down the generations, and ultimately (sometime in the Exile in Babylon) written down in the form we now have them, in the scroll entitled Bereshit, which we know as the book of Genesis?

We meet Sarai (meaning “my princess”) in the list of descendants of Terah, the father of Abraham (Gen 11:29), although (as in the Hebrews reference) it is simply noted that “Sarai was barren; she had no child” (11:30). That’s a serious roadblock in a passage that is listing descendant upon descendant!

In that same passage, we are told that Sarai, daughter-in-law of Terra, accompanied the family when they journeyed from Ur of the Chaldeans to Haran, where they settled (11:31). The journey had been intended to go as far as Canaan; that would not take place until the Lord called Abram to “go from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land that I will show you” (12:1). Sarai is there, as well as Lot and his perpetually-unnamed wife, “and all the possessions that they had gathered, and the persons whom they had acquired in Haran” (12:5).

The next story involving Sarai is perplexing and disturbing. Because of a famine, Abram “went down to Egypt to reside there as an alien” (12:10). We know that Sarai accompanies him, because he forewarns her, “I know well that you are a woman beautiful in appearance; and when the Egyptians see you, they will say, ‘This is his wife’; then they will kill me, but they will let you live. Say you are my sister, so that it may go well with me because of you, and that my life may be spared on your account.” (12:11–13).

The story is repeated twice more in Genesis; once when Abraham repeats this ruse in Gerar, before King Abimelech (20:1–7), and again when Isaac tells the same Abimelech that Rebekah is his sister (26:6–11)! It seems that the fruit does not fall far from the tree; Isaac exactly replicates his father’s devious strategy.

In between those two instances of spousal deception in Gen 12 and Gen 20, Sarai has been the cause of plagues falling onto Pharaoh and his house (12:17), settled with her husband “by the oaks of Mamre, which are at Hebron” (13:1, 18), and presumably learnt from Abram about the covenant which the Lord made with him (15:1–21)—although the text is silent about where Sarai was as this revelation came to Abram.

Sarai is front and centre, however, in the next story told, as she offers her Egyptian slave-girl, Hagar, to Abram so that he might reproduce, and fulfil the divine promise (16:1–3). Tension between the servant girl and her mistress resulted, so “Sarai dealt harshly with her, and she [Hagar] ran away from her [Sarai]” (16:6). Eventually, an angel instructed Hagar to “return to your mistress, and submit to her” (16:9), so she did, and in time bore a child to Abram.

In the next story, the circumcision of Abram and “every male among you” (17:1–27), we might wonder what role was played by Sarai. Did she witness the ceremony? Did she and her women assist those who were subjected to this procedure? Certainly, in the midst of the conversation that Abram has with God at this time, both he and his wife are given new names: “no longer shall your name be Abram, but your name shall be Abraham” (17:5), and “as for Sarai your wife, you shall not call her Sarai, but Sarah shall be her name” (17:15).

Abram, whose name describes his status in the story as “exalted ancestor”, will henceforth be known as Abraham, “ancestor of a multitude”, in keeping with the promise of God that “you shall be the ancestor of a multitude of nations” (17:4), while Sarai, “my princess”, will henceforth be known simply as “princess”, without any inflection indicating that she is “owned” by anyone.

So Sarah takes her place at the centre of the story at this point. Her status as princess means that “she shall give rise to nations; kings of peoples shall come from her” (17:16), and the birth of a son, Isaac, is predicted (17:19) and his role in continuing the lineage is confirmed (17:20). That birth is again foreshadowed when three visitors stay with Abraham and Sarah at Mamre (18:10). Sarah’s sceptical laughter (18:12) was already prefigured in the name allocated to her son, Isaac—meaning “he laughs” (17:19).

Before Isaac is born, however, the terrible story of inhospitality and divine vengeance on Sodom and Gomorrah is told in some detail (18:16–19:29), and the origins of the southern neighbours of Israel, the Moabites and Ammonites, is told (19:30–38), as well as the deception of Abraham in Gerar, when he passes the pregnant Sarah off as his sister (20:1–7).

Then comes the birth of Isaac (21:2–3), after which she rejoices, “God has brought laughter for me; everyone who hears will laugh with me” (21:6)—after which Sarah again orders Hagar, and also Ishmael, to depart into the wilderness. Sarah instructs Abraham to “cast out this slave woman with her son” (21:10); “the matter was very distressing to Abraham on account of his son” (21:11).

And so the schism between Abraham and Sarah is opened up; the events of the next incident, when Abraham takes Isaac to a mountain in Mariah, to sacrifice him (22:1–3), appear to seal the split. As I was talking with my wife, Elizabeth Raine, about this difficult story last week, she pointed out to me that we do not see Abraham and Sarah together in the same place after this.

Abraham now appears not to be living with his wife, Sarah—he is in Beersheba, with his servants (22:19) whilst Sarah remains at Hebron, where she dies (23:1–2). Was this because of the tension that grew between the patriarch and the matriarch after he had almost sacrificed his son? This is the story we read last week; see

Tensions were already evident earlier in the story, when Sarah had banished Hagar and Ishmael into the wilderness of Beersheba (21:10–14). To send them on their way, Abraham made sure that they had bread and water to sustain them in the wilderness (21:14). As Elizabeth noted, we do not see Abraham and Sarah together again in the story.

It is only on her death that Abraham travels to where Sarah had been living, in Hebron, some 42km further north. Abraham sought to purchase a field there to serve as the burial place for Sarah. Ephron the Hittite, moved with compassion, wanted to gift him a field with a cave where Sarah’s body could be laid (23:7–12), but Abraham insisted and paid Ephron the value of the field, 400 shekels of silver (23:12–16). He dies at least honour her appropriately at the point of her death.

*****

Writing in My Jewish Learning, Jewish educator Rachael Gelfman Schultz notes that “Genesis contains the greatest concentration of female figures in the Bible (32 named and 46 unnamed women). The fact that Genesis consists of a series of family stories (including several genealogies) accounts for the remarkable concentration of female figures.” Sarah is an important figure in that list of women. Rabbinic tradition lists her among the seven women prophets, the others being Miriam, Deborah, Hannah, Abigail, Huldah, and Esther.

See https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/sarah-in-the-bible/

Nissan Mindel, writing in Chabad.org, observes that “Sarah was just as great as Abraham. She had all the great qualities that Abraham had. She was wise and kind, and a prophetess. And G‑d told Abraham to do as she says.”

He describes the home that they made in Beersheba, noting that whilst Abraham received visitors, offered them hospitality, and conversed with them (following the pattern shown in Gen 18), “Sarai was busy with the women folk, and long after all visitors were gone, or had retired to sleep, Sarai would sit up in her tent, making dresses and things for the poor and needy.

“When everybody was fast asleep, there was still a candle burning in Sarai’s tent, where she was sitting doing some hand-work, or preparing food for the next day. So G‑d sent a special Cloud of Light to surround her tent. For miles and miles around, the Cloud of Glory could be seen hovering over Sarai’s tent, and everybody said, “’There dwells a woman of worth.’”

See https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/112057/jewish/Abraham-And-Sarah.htm

So there is much to value, and honour, about Sarah, princess, prophet, and matriarch supreme. We would do well not to overlook her, the matriarch of matriarchs, amidst the stories of the patriarchs.

Among egalitarian religious congregations of Jews throughout the world, the most popular addition to the traditional liturgy is the mention of the Matriarchs in birkat avot (the blessing of the ancestors), the opening blessing of the Amidah:

Praised are You, Adonai our God and God of our ancestors, God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, God of Sarah, Rebekah, Rachel, and Leah, great, mighty, awesome, exalted God who bestows lovingkindness, Creator of all. You remember the pious deeds of our ancestors and will send a redeemer to their children’s children because of Your loving nature.

https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/matriarchs-liturgical-and-theological-category