For this coming Sunday, the lectionary provides us with part of a larger story from the section of Genesis dealing with Abraham (Gen 24:34–38, 42–49, 58–67). As Abraham’s son Isaac comes to age, Abraham knows that there is a need to find him a wife.

Abraham now appears not to be living with his wife, Sarah—he is in Beersheba, with his servants (22:19) whilst Sarah remains at Hebron, where she dies (23:1–2). Was this because of the tension that grew between the patriarch and the matriarch after he had almost sacrificed his son? This is the story we read last week; see

Tensions were already evident earlier in the story, when Sarah had banished Hagar and Ishmael into the wilderness of Beersheba (21:10–14). To send them on their way, Abraham made sure that they had bread and water to sustain them in the wilderness (21:14). We do not see Abraham and Sarah together again in the story. In discussing this with my wife, Elizabeth Raine, last week, she proposed that Sarah was so upset with Abraham’s actions on Mount Mariah, threatening the life of their son Isaac (Gen 22:1–14), that she left him behind at Beersheba and moved to Hebron, some 42km to the north.

It is only on her death that Abraham travels to where Sarah had been living, in Hebron. Abraham sought to purchase a field there to serve as the burial place for Sarah. Ephron the Hittite, moved with compassion, wanted to gift him a field with a cave where Sarah’s body could be laid (23:7–12), but Abraham insisted and paid Ephron the value of the field, 400 shekels of silver (23:12–16). So he was doing the honourable thing for his wife after her death, even though there seems to have been a relationship breakdown prior to this.

Despite the fact that he willingly enters into these dealings with the Hittites in Beersheba, and the fact that he had earlier entered into a covenant with Abimelech, King of Gerar, a Philistine (21:22–34), Abraham is now concerned that Isaac not marry locally, to a Canaanite, but that a wife be found for him in “my country” and amongst “my people”, as he instructs his servant (24:4–5).

We may perhaps know of people who share that desire that their children not marry “foreigners”, but find a partner from amongst their own. So it is an ancient story with very modern resonances. Marlene Andrews, Church leader at Ngukurr, shares her perspective on this passage in the current issue of With Love to the World, a daily Bible study resource.

(Ngukurr is a town of about 1,000 people, located about 330 kilometres south-east of Katherine on the Roper Highway. Ngukurr is one of the largest Aboriginal communities in the Roper Gulf region.)

She says: “This story is about Abraham, his son. Abraham wanted the best for his son in marriage. Abraham knew that God was with him at the time of his decision-making. Abraham was faithful to God’s calling. Abraham knew how to go about finding a good wife for his son, Isaac. It was important that his son’s wife came from Abraham’s country. That is where Abraham came from, and where he wanted his son to connect to. Abraham knew the culture and the background of his people. Abraham knew in finding a wife for his son, she had to come from his homeland.”

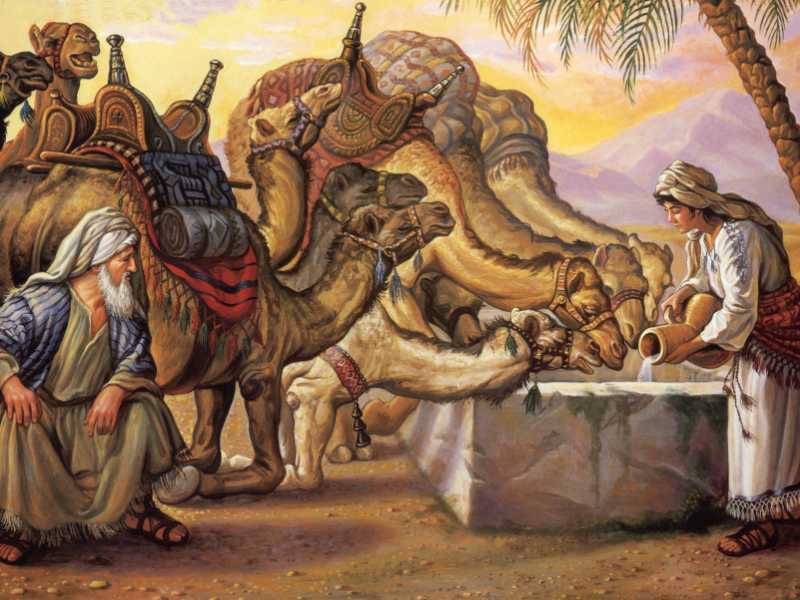

The marriage is arranged, at a distance, by Abraham. Isaac plays no part in the whole saga that is recounted in detail in Genesis 24. Abraham sends his servant all the way north to a well near the city of Nahor, which was back in Aramea, the homeland of Abraham. This was in the area we know as the Fertile Crescent, in between the two rivers of the Tigris and the Euphrates (24:10). The well near Nahor becomes the location for the match-making that Abraham undertakes, through the servant whom he sent there (24:10–14).

Isaac will, much later in time, notice Rebekah, the daughter of Bethuel, “son of Milcah, the wife of Nahor, Abraham’s brother” (24:15), but this is not until the story has almost come to its close (24:62–67). It is understandable that Isaac was agreeable to the arrangement that his father had made, for “the girl was very fair to look upon, a virgin, whom no man had known” (24:16).

This last comment is important, in the light of the drastic provision in the Torah that, if evidence of the young woman’s virginity is lacking, “they shall bring the young woman out to the entrance of her father’s house and the men of her town shall stone her to death, because she committed a disgraceful act in Israel by prostituting herself in her father’s house” (Deut 22:21).

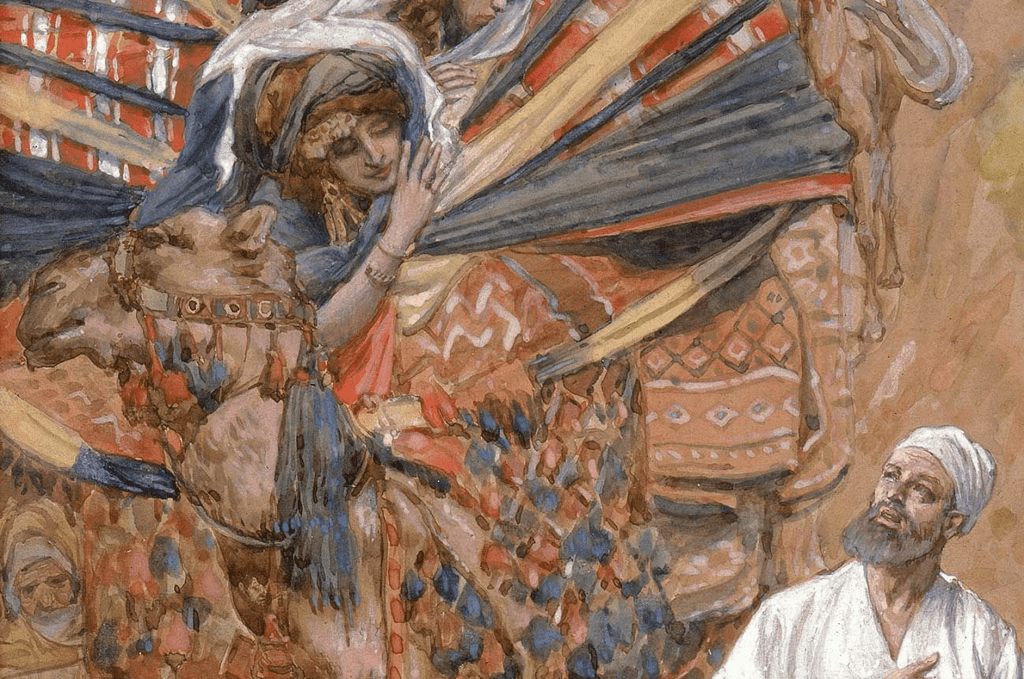

Reckoning that the woman was able to be considered for marriage (we have to trust the insight of the narrator at this point), the servant was prepared for what he hoped would transpire; he had with him “a gold nose-ring weighing a half shekel, and two bracelets for her arms weighing ten gold shekels” (24:22).

After Rebekah has brought her brother Laban into the story (24:28–29), and he noticed the nose-ring and bracelets (24:30), he offered hospitality to the servant, which was duly accepted (24:31–33). The purpose of the nose-ring and bracelets is then revealed—although surely those who heard this story in antiquity would be well aware of their significance. Brokering a marriage is the clear intention (24:34–41).

The woman had had a ring placed in her nose, and bracelets put around her arms (24:47); the action presumably took place at 24:22–27, although it was not explicitly narrated there. The ring and bracelets were obviously the custom for women in the time when the story was initially told, and they held their place within the story as it was passed down from generation to generation, even if customs may have changed.

Marriage customs do vary across time and place, from one culture to another. What held in the days of the patriarchs (or, at least, in the days in ancient Israel when people told stories about how they imagined things were in the “olden days” of the patriarchs) does not necessarily hold good for our time, today. A story of a man who married a woman so that, after a prescribed period of time (seven years!) he could marry her sister, as was the case with Jacob, Rachel, and Leah (Gen 29–30), for instance, would not hold today! And whilst rings remain the most common sign of a marriage, they are placed around fingers, and not into noses, in most modern cultures!

So Isaac, eventually, enters the story (some 47 verses after Rebekah was first introduced!). He notices, first, the camels which had come all the way from Nahor to the Negeb (24:62–63); and then, “Isaac brought her into his mother Sarah’s tent; he took Rebekah, and she became his wife; and he loved her” (24:67). All is well, that ends well—thanks to the well!

However, even though Isaac had never been to the well at Nahor where the marriage agreement was made, this well was the first of a number of wells where marriages were negotiated and confirmed within the sagas of ancient Israel. Jacob met his wife-to-be, Rachel, beside a well in Canaan, later Samaria (Gen 29:1–3). Moses, when travelling in Midian, “sat down by a well”, where, in due time, the local priest Jethro gave one of his daughters, Zipporah, to Moses in marriage (Exod 2:15–21).

The well in Canaan, known as Jacob’s well, is much later on the location for another famous encounter, between Jesus of Nazareth and an unnamed woman of Samaria (John 4:4–30)—although no marriage resulted from this encounter!

The two marriages, of the son and grandson of Abraham, which resulted from encounters beside the two wells, are important, for they demonstrate that the promise made to Abraham, of many descendants who will be blessed by God (Gen 12:2–3), will be guaranteed. Sure enough, Isaac and Rebekah produce twin boys, Esau and Jacob; and Jacob, in turn, is the father of twelve sons, whose names provide the identification of the twelve tribes of Israel. So these wells are integral to the divine promise!

Isaac was the son of Abraham; Rebekah was the granddaughter of Nahor, the brother of Abraham; so they were cousins. Tracy M. Lemos, Associate Professor of Hebrew Bible and ancient Near Eastern language and literature in the Faculty of Theology of Huron University College at Western University in London, Ontario, writes in Bible Odyssey that “Biblical texts make clear that marriages between cousins were strongly preferred”. She continues, “different Israelite communities and authors had diverse viewpoints on marriage and that Israelite viewpoints evolved over time”. See

https://www.bibleodyssey.org/passages/related-articles/weddings-and-marriage-traditions-in-ancient-israel/

The conclusion of Prof. Lemos, that “many biblical customs would be unfamiliar or even objectionable to many people living in western societies today”, certainly stands with regard to the passage we are offered for this coming Sunday. The detailed story that is told in Gen 24 is a fascinating insight into another world, another time, another culture. Yet it is part of our shared heritage, as Jews and Christians, in the modern era. It is good to hear the story, once again, as the lectionary offers it to us this Sunday.