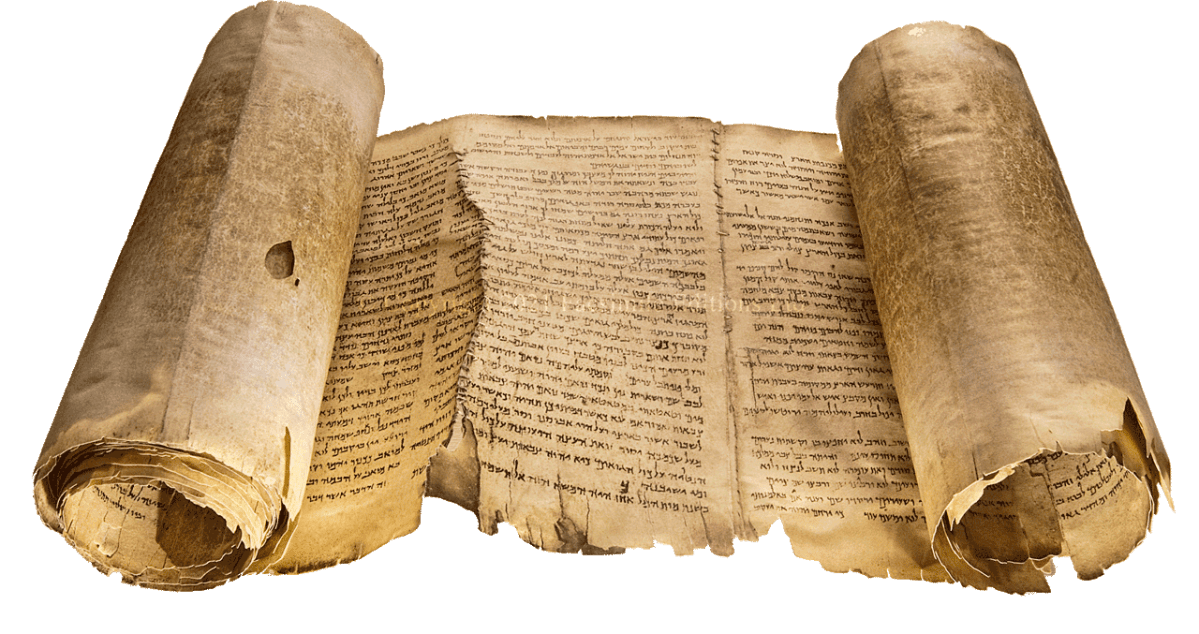

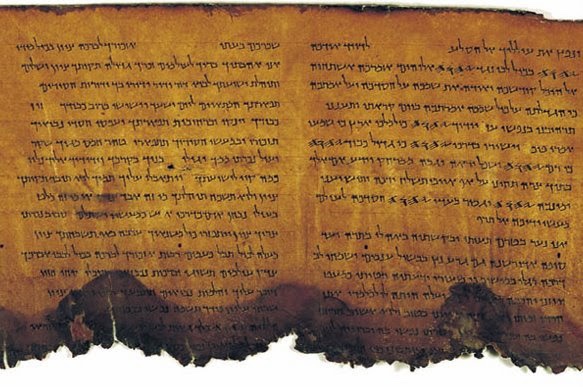

Psalm 119, the longest of all psalms, is the 176–verse grand acrostic of the Hebrew Scriptures (22 section s of eight verses each, commencing in order with the letters of the Hebrew alphabet. A small portion of this psalm (119:105–112) is offered by the lectionary this coming Sunday. I am exploring the questions: what would a theology look like, using only the verses in this psalm? and how full (or inadequate) would that theology be? See earlier instalments at

6 The life of a faithful person

So a sixth element in the psalm, which also correlates with a standard section in a fully-developed theology, is what it says about the life of a faithful person. This life is characterised most strikingly by delight—a quality that is articulated ten times in the psalm. The second section ends in a paean of praise: “I delight in the way of your decrees as much as in all riches. I will meditate on your precepts, and fix my eyes on your ways. I will delight in your statutes; I will not forget your word.” (vv.14–16).

The psalmist continues, “your decrees are my delight, they are my counselors” (v.24); “lead me in the path of your commandments, for I delight in it” (v.35); “I find my delight in your commandments, because I love them” (v.47); “I delight in your law” (v.70), “your law is my delight” (v.77, 174); “your commandments are my delight” (v.143); and, most powerfully, “if your law had not been my delight, I would have perished in my misery” (v.92). The requirements of the law bring delight to the person of faith.

A second characteristic of the life of a person of faith is that it is marked by love. In typical style, this love—which is a response to the steadfast love of God (see above)—is focussed on Torah, the source of knowledge about, and relationship with, God. Nearing the end of the psalm, we hear the psalmist say, “consider how I love your precepts; preserve my life according to your steadfast love” (v.159), drawing together the two expressions of love—love of God for humans, love of humans for God’s word in Torah.

The psalmist exults, “I find my delight in your commandments, because I love them; I revere your commandments, which I love, and I will meditate on your statutes” (vv.47–48). They exclaim, “Oh, how I love your law! It is my meditation all day long” (v.97) and affirm that “truly I love your commandments more than gold, more than fine gold” (v.127).

So much is Torah valued, that it apparently offers perfection: “I have seen a limit to all perfection, but your commandment is exceedingly broad” (v.96). In this regard, the psalmist’s appreciation for Torah as perfection seems to reflect the priestly desire for people to offer perfect sacrifices, without blemish (Lev 22:21), and Solomon’s desire to build the Temple as a perfect house for God (1 Ki 6:22).

Indeed, such a conception of perfect Torah also resembles the sage’s musings regarding Wisdom: “to fix one’s thought on her is perfect understanding” (Wisdom 6:15), and thoughts found in a prayer attributed to Solomon: “even one who is perfect among human beings will be regarded as nothing without the wisdom that comes from you” (Wisdom 9:6).

The writer clearly loves Torah. This love leads to joy: “your decrees are my heritage forever; they are the joy of my heart” (v.111). Joy is manifest in praise: “let me live that I may praise you, and let your ordinances help me” (v.175). And God’s love also provides comfort: “let your steadfast love become my comfort according to your promise to your servant” (v.76). This is the fulfilment of God’s promise to the believer: “let my supplication come before you; deliver me according to your promise” (v.170).

The psalmist prays “give me life” a number of times, linking this life with God’s ways (v.37), righteousness (v.40), word (v.107), promise (v.154), and justice (v.156). In return, the psalmist makes a whole-of-being commitment; this is the way I believe that the Hebrew nephesh should be translated. (It is regularly translated as “soul”, but this fails to convey the sense that the Hebrew has, of the whole of a person’s being.)

So the author prays, “my [whole being] is consumed with longing for your ordinances at all times” (v.20), “your decrees are wonderful; therefore my [whole being] keeps them” (v.129), and “my [whole being] keeps your decrees; I love them exceedingly” (v.167).

Another way that the Hebrews spoke about the whole of a person’s being was to refer to the “heart” (Hebrew, leb). The psalmist opens with the declaration, “happy are those who keep [God’s] decrees, who seek him with their whole heart” (v.2), place the phrase about seeking “with their whole heart” in apposition to “walk in the law of the Lord” (v.1). With their heart, the psalmist praises God (v.7), seeks God (v. 10), implores God’s favour (v.58), and cries to God (v.145).

The psalmist’s heart “stands I awe of [God’s] words” (v.161), and it is in their heart that they treasure God’s word (v.11), observe God’s law (v.34), and keep God’s precepts (v.69). Truly “your decrees are my heritage forever; they are the joy of my heart; I in line my heart to perform your statutes forever, to the end” (vv.111-112). Diligence in attending to Torah is clearly to the benefit of the psalmist; they pray, “may my heart be blameless in your statutes, so that I may not be put to shame” (v.80).

Likewise, shame is avoided when the psalmist looks towards the commandments (v.6). They confess that, as they are “looking at vanities”, God needs to “turn their eyes”(v.37); they confess, “my eyes shed streams of tears because your law is not kept” (v.136). So it is with their whole being (nephesh), their whole heart (leb), and also with their eyes (ayin) that the psalmist demonstrates this whole of being commitment to Torah. “I will meditate on your precepts and fix my eyes on your ways” (v.15), they pray; and yet these eyes “fail from watching” (vv.82, 123), so the psalmist petitions, “open my eyes” (v.18).

With knowledge of Torah, the psalmist is able to walk in God’s way. “Your word is a lamp to my feet and a light to my path” (v.105) is the best known statement of this; but we have also “when I think of your ways, I turn my feet to your decrees” (v.59) and “I hold back my feet from every evil way, in order to keep your word” (v.101).

Finally, along with sight and touch, the sense of taste is engaged in responding to God. “How sweet are your words to my taste”, the psalmist sings, “sweeter than honey to my mouth!” (v.103). These words are reminiscent of the same praise in Psalm 19, when reflecting on the words of Torah:”more to be desired are they than gold, even much fine gold; sweeter also than honey, and drippings of the honeycomb” (Ps 19:10).

7 The future

Most classic articulations of a full theology end with a view looking forward into the future. This is perhaps the least-developed aspect of Psalm 119. The writer is focussed on obedience to Torah in the present, simply as an expression of faithfulness and commitment. There is full acceptance of the Deuteronomic view that this life is when God rewards those who are faithful and punishes disobedience and evil. There is not yet any sense of the later Pharisaic development that there will be a “resurrection of the dead” and that rewards (and punishments) can be deferred to be experienced in the afterlife.

For the psalmist, the future is simply as far ahead within this life as can be envisaged. In light of that, they sing to God, “your faithfulness endures to all generations; you have established the earth, and it stands fast” (v.90). Throughout all of those generations, what is required is continuing faithfulness: “long ago I learned from your decrees that you have established them forever” (v.152), and so “I incline my heart to perform your statutes forever, to the end” (v.112), for “every one of your righteous ordinances endures forever” (v.160). The psalmist prays, “your decrees are righteous forever; give me understanding that I may live” (v.154).

The viewpoint has strong resonances with words of Jesus which Matthew reports: “until heaven and earth pass away, not one letter, not one stroke of a letter, will pass from the law until all is accomplished” (Matt 5:18).

Indeed, what undergirds this confidence is the affirmation that “the Lord exists forever; your word is firmly fixed in heaven” (v.89). That stanza continues with deep assurance, “your faithfulness endures to all generations; you have established the earth, and it stands fast; by your appointment they stand today, for all things are your servants” (vv.90–91).

Whatever may come, it seems, the author of this psalm will hold fast with confidence to the way set before them. It is as if they “lay aside every weight and the sin that clings so closely, and … run with perseverance the race that is set before us”—although, rather than “looking to Jesus the pioneer and perfecter of our faith” (Heb 12:1–2), they look to Torah as the foundation and indeed the perfection of their faith (cf. Ps 119:96).