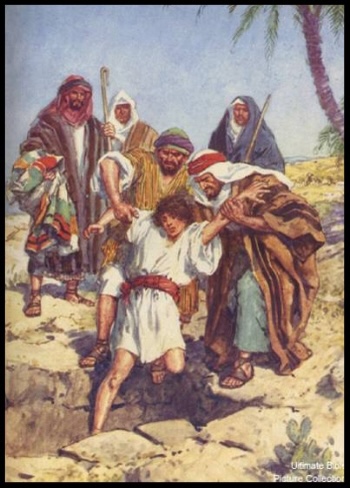

“Here comes this dreamer. Come now, let us kill him and throw him into one of the pits; then we shall say that a wild animal has devoured him, and we shall see what will become of his dreams” (Gen 37:19–20). There it is: “brotherly love” on display, for everyone to see!

The sons of Jacob, who became the sons of Israel, and then gave their names to “the twelve tribes of Israel”, as we saw in an earlier blog, are terrible role models. They show us fraternal jealousy and hatred at its worst. The story offered by the lectionary for this coming Sunday, Pentecost 11A, pulls no punches (37:1–4, 12–28). These sons could be mean!

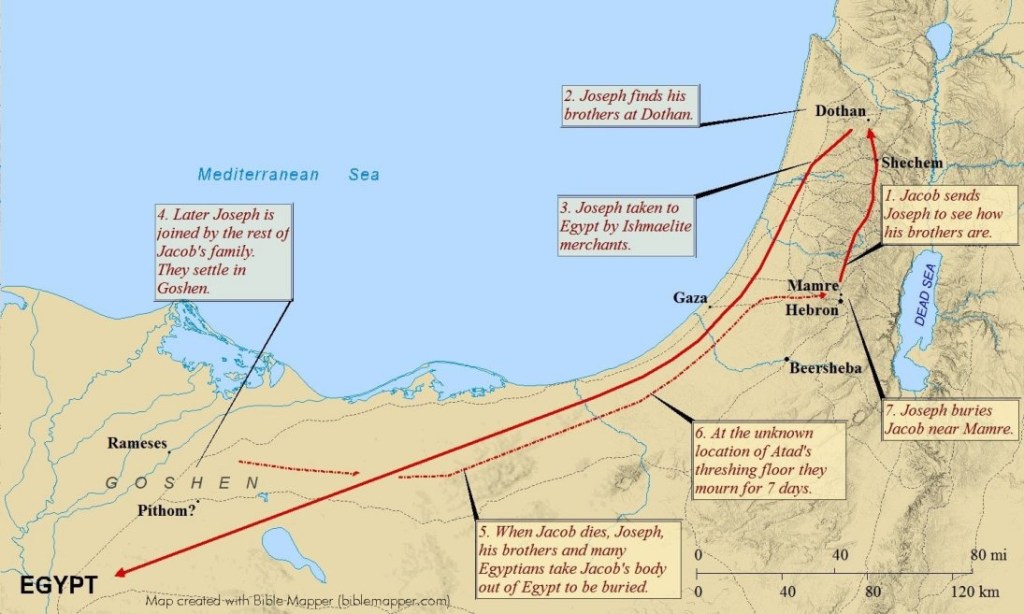

We have left behind the stories of the three patriarchs of Israel, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and their wives, the four matriarchs Sarah, Rebekah, Leah, and Rachel—although Jacob is still alive, and he will figure in some of the final scenes of Genesis in chapters 46 and 48—50. We turn our attention to Joseph, who had been born to Jacob’s wife Rachel, after years of waiting.

Only after his first wife Leah had given birth to six sons and a daughter, did Rachel give birth, as God “heeded Rachel and opened her womb” (Gen 30:22). As a sign of the passing of her barren state, Rachel declared, ‘God has taken away my reproach’; and we read that “she named him Joseph, saying, ‘May the LORD add to me another son!’ (Gen 30:23). That son, Benjamin, came years later, although Rachel tragically died giving birth (Gen 35:16–20).

We meet Joseph in the passage offered by the lectionary, which notes that, as he grew, Joseph was the favoured son (Gen 37:3). Of course, this fostered the jealousy of his brothers, who “hated him, and could not speak peaceably to him” (Gen 37:4). And so the scene is set for the problematic sequence of events that ensues, as his brothers initially plot to kill him (Gen 37:19–20), before Reuben intervenes (Gen 37:21–23).

We have already seen that the ethical standards of the people in these ancestral stories leaves something to be desired. Cheating, stealing, rape, incest, murder, and double dealing appear to be par for the course. Yet these brothers who plot to kill Joseph are the men who give their names to the tribes of Israel—names that are given pride of place in the priestly garments (Exod 1:1–4; 28:9–12, 21, 29; 39:6–7, 14) and in the later history of the people (1 Chron 2:1–2).

That these stories of their murky ways of operating have been preserved, passed on, and preached on with regularity, is quite remarkable! Perhaps we should reflect that human beings have always been flawed? Or that we should well expect that the ethical standards and cultural practices of our time are different from what held sway in past eras?

And perhaps we need also to note—and take caution from the observation—that this particular incident, selling Joseph for twenty pieces of silver, has fed into the unhelpful stereotype of the Jews who are always and in every way concerned about money. It’s a stereotype that has fed the burgeoning antisemitic attitude and actions of people throughout the Middle Ages, past the Enlightenment on into the modern age—culminating, of course, in the horrors of the Shoah (Holocaust) in Nazi Germany.

See

https://antisemitism.adl.org/greed/

Back to the story of Genesis 37. That the brothers plot to kill Joseph, and are only dissuaded by the intervention of Reuben (Gen 37:21–23), is clearly a mark against them. That Judah then suggests that they sell him to a passing caravan of Ishmaelites (Gen 37:25–28), whilst it saves the life of Joseph, is yet another mark against the brothers.

Christian readers will perhaps compare the “twenty pieces of silver” that was paid for Joseph (Gen 37:28) with the thirty pieces of silver paid to Judas for handing Jesus over to the authorities (Matt 26:15). However, a number of passages in Hebrew Scriptures provide a more fitting contrast to the price paid for Joseph.

Abimelech, in his unsuccessful attempt to install himself as king in Israel, took “seventy pieces of silver out of the temple of Baal-berith with which [he] hired worthless and reckless fellows, who followed him” (Judg 9:4). So twenty pieces are significantly less.

And the story is told in Judges about when the lords of the Philistines bribed Delilah with eleven hundred pieces of silver to hand over Samson to them (Judg 16:5; 17:1–5), and in the Song of Songs the (poetically-exaggerated) claim is made that Solomon expected a thousand pieces of silver from each of the keepers of his vineyard (Song 8:11). So twenty pieces pales into utter significance, by comparison. Was Joseph worth so little.

The irony is that Israel as a whole is identified with reference to Joseph at a number of places in the Hebrew Scriptures. Both narrative texts and prophets refer to the whole nation as “the house of Joseph” (Josh 17:17; 18:5; Judg 1:22–23, 35; 2 Sam 19:20; 1 Ki 11:28; Amos 5:6; Obad 1:18; Zech 10:6).

The psalms sing of “the descendants of Jacob and Joseph” (Ps 77:15) and bring petitions to God, “Shepherd of Israel, you who lead Joseph like a flock” (Ps 80:1). Psalm 81 places Joseph alongside Jacob and Israel: “it is a statute for Israel, an ordinance of the God of Jacob, he made it a decree in Joseph, when he went out over the land of Egypt” (Ps 81:4–5). The name of Joseph was revered in the ongoing traditions of Israel.

So let us treasure and reflect on this story, in which Joseph is sold off to foreign travellers. His life had been saved from the plotting of his brothers by a compassionate intervention by one of their number; but he is taken off into Egypt—for what fate?

*****

Reading the story chapter-by-chapter, as it appears in Genesis, we don’t yet know the significance of Egypt (other than the account of the time that Abram and Sarai spent in Egypt in Gen 12:10–13:12). But people hearing the story when it was written into the scrolls, after the return from Exile, would know of the time of slavery spent by their ancestors in Egypt, when “the Egyptians became ruthless in imposing tasks on the Israelites, and made their lives bitter with hard service” (Exod 1:13–14). They know the ominous threat that lies over Joseph at the end of this week’s story: “they took Joseph to Egypt” (Gen 37:28).

That fate is symbolised by the note in the immediately following verses, that the brothers of Joseph dipped his coat into the blood of a slaughtered goat and brought it back to Jacob. When Jacob recognized the coat, he concluded that “a wild animal has devoured him; Joseph is without doubt torn to pieces” (Gen 37:33). Jacob mourned for many days; despite the best efforts of his family, “he refused to be comforted, and said, ‘I shall go down to Sheol to my son, mourning” (Gen 37:35).

The narrative leaves Joseph with the tantalising comment that he was sold by the Midianites to Potiphar, one of Pharaoh’s officials (Gen 37:36), before veering off to tell a long story about Judah and Tamar (Gen 38). The question remains: what fate awaits Joseph?