The lectionary, in characteristic style, picks and chooses select passages that it offers, week by week, as we move through the ancestral narratives that have been collected and consolidated in Genesis. As we have noted before, these stories have been told and retold, collected and written down, because they have shaped the self-understanding and identity of the ancient nation of Israel.

Written in the form that we now have them by the priests who had held the stories of Israel through the decades of Exile, these stories comprise oral tales, told and retold over centuries before that Exile, remembered and passed on because they offered insights into who the people of Israel had become—committed, resilient, crafty, and faithful. They have the nature of aetiology, explaining character through narrative, and they function as myths, or stories told in an entertaining style that are designed to convey important information .

So this week we jump from last Sunday’s tale of Joseph, sold off to the Egyptians (Gen 37), to this coming Sunday’s fraternal encounter. We now find Joseph as an important official in the court of Egypt, confronted by his starving brothers, who are begging for help from the grain-rich Egyptians (Gen 43–45). What has happened in between these two stories?

First, Potiphar made Joseph his personal attendant; he was in charge of the entire household. There is a subplot concerning Potiphar’s wife and Joseph, resulting in Joseph being imprisoned (Gen 39; but the lectionary skips over this). However, the chief gaoler liked Joseph and put him in charge of all the other prisoners, including Pharaoh’s butler and baker. One night both the butler and the baker had strange dreams, which Joseph interpreted in ways that soon came true. Joseph gained a reputation as a dream interpreter (Gen 40; again, we jump over this).

Two years later, Pharaoh had two dreams that his magicians could not interpret. Joseph was summoned and told Pharaoh that the dreams forecasted seven years of plentiful crops followed by seven years of famine. Following Joseph’s advice, Pharaoh made Joseph his second-in-command. He gave Joseph his ring and dressed him in robes of linen with a gold chain around his neck. Pharaoh gave him the Egyptian name Zaphenath-paneah and found him a wife named Asenath, daughter of Poti-phera the priest of On (Gen 41, not included in the lectionary).

Joseph traveled throughout Egypt, gathering and storing enormous amounts of grain from each city. During these years, Asenath and Joseph had two sons: Manasseh, meaning, “God has made me forget (nashani) completely my hardship and my parental home, and Ephraim, meaning, “God has made me fertile (hiprani) in the land of my affliction”. These sons, grandsons to Jacob, would later have a key role (but the lectionary doesn’t include this part of the story).

After seven years, a famine spread throughout the world, and Egypt was the only country that had food. Joseph was in charge of rationing grain to the Egyptians and to all who came to Egypt. The famine affected Canaan, so Jacob sent ten of his sons to Egypt. He kept back Benjamin, Rachel’s second son and Jacob’s youngest child, the son who had intervened to save Joseph years earlier (Gen 42).

The story assumes a rollicking-good-yarn feeling, as Joseph recognises the brothers but does not let on, and sends them back to Canaan. He kept Simeon in jail pending their return with Benjamin, as instructed, despite Jacob’s misgivings (Gen 43).

The brothers return to Egypt with Benjamin, along with a gift for Joseph as well as double the necessary money to repay the money that was returned to them. Again, there is a comedy-of-errors feel, as Joseph acts is if he does not know the brothers when they actually do; in the end he instructed his servant to fill the brothers’ bags with food, return each one’s money a second time, and put his own silver goblet in Benjamin’s bag. Then he sends his servant after them, to accuse them of theft. Benjamin is detained; Judah pleads with Joseph to release him (Gen 44). Will he do so?

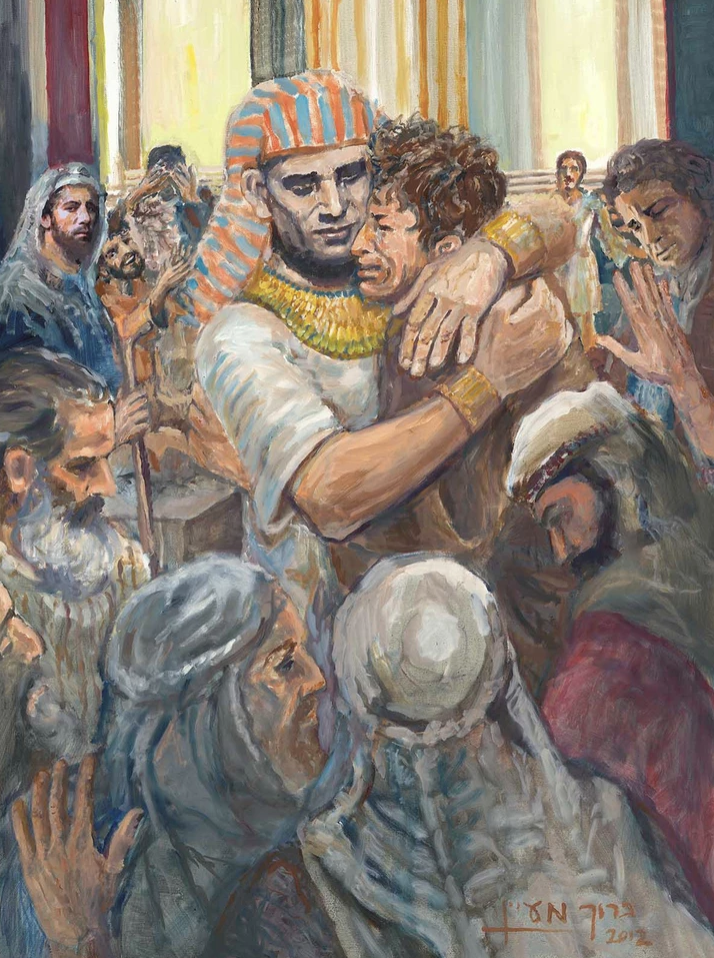

This is the point at which the lectionary takes up the story (Gen 45:1), as Joseph reveals his true identity to his brothers. It is a narrative that is fraught with emotion: Joseph could no longer control himself (v.1), he wept loudly (v.2), his brothers are dumbstruck and dismayed (v.3). After a lengthy speech of explanation (vv.4–13), Joseph bursts into tears, as does Benjamin (v.14), and then Joseph “kissed all his brothers and wept upon them” (v.15). The emotions are deep-seated and visceral; the physical actions described signal the profound effect that the experiences have had on Joseph and his brothers.

What does this note mean, that Joseph “fell upon his brother Benjamin’s neck” (v.14)? A discussion of this story on the Jewish website chabad.org notes that these chapters of Genesis tell “no mere family drama. The twelve sons of Jacob are the founders of the twelve tribes of Israel, and their deeds and experiences, their conflicts and reconciliations, their separations and reunions, sketch many a defining line in the blueprint of Jewish history.”

In particular, the website (based on the teachings of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, the leader of the ultra-conservative Chanda-Lubavitcher movement, adapted by Yanki Tauber) comments that “The Talmud (Megillah 16b) interprets their weeping on each other’s necks as expressions of pain and sorrow over future tragedies in their respective histories”.

The website offers the Talmudic explanation: “[Joseph] wept over the two Sanctuaries that were to stand in the territory of Benjamin and were destined to be destroyed … and Benjamin wept over the Shiloh Sanctuary that was to stand in the territory of Joseph and was destined to be destroyed.”

Through a series of rabbinic treatments of biblical texts concerning “the neck” and “the Temple”, the conclusion is drawn: “The Sanctuary is the “neck” of the world, the juncture that connects its body to its head. A person’s head contains his highest and most vital faculties — the mind and the sensing organs, as well as the inlets for food, water and oxygen — but it is the neck that joins the head to the body and channels the flow of consciousness and vitality from the one to the other: the head heads the body via the neck. By the same token, the Holy Temple is what connects the world to its supernal Vitalizer and source. It is the channel through which G‑d relates to His creation and imbues it with spiritual perception and material sustenance.”

So rabbinic midrashic interpretation sees deep significance in the comments about Joseph and Benjamin each “falling on the neck” (Gen 45:14). See

https://www.chabad.org/parshah/article_cdo/aid/3222/jewish/The-Neck.htm

The scene is also marked by tears. When “he fell upon his brother Benjamin’s neck”, Joseph wept (Gen 45:14). There have been tears before in the stories told in Genesis. When he first meets his cousin, “Jacob kissed Rachel, and broke into tears” (Gen 29:11). Reunited with Jacob, “Esau embraced him and, falling on his neck, he kissed him; and they wept” (Gen 33:4).

There are more tears after this particular story concerning Joseph, too. Reunited with his father, Jacob, Joseph embraces “him around the neck [and] wept on his neck a good while” (Gen 46:29). When Jacob dies, “Joseph flung himself upon his father’s face and wept over him and kissed him” (Gen 50:1). After his father’s death, when his brothers tell him that Jacob had commanded Joseph not to seek revenge, “Joseph was in tears as they spoke to him” (Gen 50:17).

Writing on this story on the Haaretz website, Dr Ariel Seri-Levi, of the Ben Gurion University of the Negev, notes that there were three reasons for weeping in Hebrew Bible stories: mourning for a dead person (Abraham for Sarah, at Gen 23:2; the prophet for Jerusalem at Lam 1:16; Joseph as Jacob dies, at Gen 50:1); distress directed toward a leader, either divine or human (the Israelites in the wilderness, Num 11:4, or the residents of Jabesh Gilead, 1 Sam 11:4–5); and weeping on “an encounter or reunion between relatives or close friends”. The weeping of Joseph, and Benjamin, in this scene, is of this nature.

Dr Seri-Levi writes that such “weeping confirms and expresses their bond. Thus, weeping does not necessarily express an emotional collapse or inner turmoil; conversely, a person’s avoidance of weeping does not necessarily reflect indifference.” He relates this to the need that Joseph had, initially, to conceal his identity, and then, at the release when he felt able to reveal his identity. It is a part of the craft of the storyteller, deployed to intensify emotion in the listener, or reader. It is a way to ensure we find ourselves “in the story”, right in the midst of all that is taking place.

*****

The section offered by the lectionary ends, then, in a very prosaic manner: “and after that his brothers talked with him” (Gen 45:15). The fractured relationships amongst the twelve has been repaired; the lines of communication between estranged individuals have been restored. It just remains for this to be communicated to Jacob—which is done in the rest of chapter 45. Jacob and his whole family, sixty-six persons in all, relocate to Egypt (Gen 46), but famine eventually strikes even Egypt (Gen 47).

Beyond the lectionary offerings from Genesis (since we jump, on the following Sunday, to Exodus 1), the book concludes with grand scenes of blessing and farewell. Jacob blesses Joseph (Gen 48:15–16), Joseph’s sons Ephraim and Manasseh (Gen 48:17–22), and then the full complement of his twelve sons (Gen 49:1–28), before Jacob dies amd is buried (Gen 49:29—50:14). In due time, Joseph himself comes to the end of his earthly life; aged 110, he was “embalmed and placed in a coffin in Egypt” (Gen 50:26).

There is a longer summary of the full saga that is told in the Joseph section of Genesis (chapters 37–40) in the Jewish Virtual Library at https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/joseph-jewish-virtual-library