The Hebrew Scripture reading for this coming Sunday contains a set of well-known words—the Ten Commandments (Exod 20:1–20), given to Moses on Mount Sinai, for him to take down to the people of Israel as their set of guidelines for faithful living within the covenant. That covenant was sealed by God and Moses in the previous chapter (19:1–8).

These words set the pattern for life that the Israelites are to follow. They accept and commit to this way of life, declaring “everything the Lord has spoken we will do” (19:8). Those Ten Commandments are then followed by multiple other commands for living (20:22—23:19). It is these commands that the people are instructed to live by, to which they again make their commitment: “all the words that the Lord has spoken we will do” (24:3).

Moses then confirms this in a very public way: he arranged for “burnt offerings and sacrificed oxen [to be] offerings of well-being to the Lord”, as well as dashing half of the blood from those offerings against the altar he had constructed (24:5–6).

Then we read that Moses “took the book of the covenant, and read it in the hearing of the people; and they said, ‘All that the Lord has spoken we will do, and we will be obedient’” (24:7)—and the remaining half of the blood from the offerings was dashed on the people, who are told “see, the blood of the covenant that the Lord has made with you in accordance with all these words” (24:8).

What do we make of these familiar words? The Ten Commandments are probably one of the most well-known passages in Hebrew Scripture—even if most people would struggle to identify the specific requirements of all ten of the commandments. It’s more “the vibe of the thing” that we recall, rather than the precise words.

Here are ten things about these Ten Commandments that help us to understand and appreciate their significance—both in Judaism, the religion that developed from ancient Israelite practices, as well as in Christianity, which appropriated the stories, songs, oracles, and teachings of Judaism as the foundation for its own development.

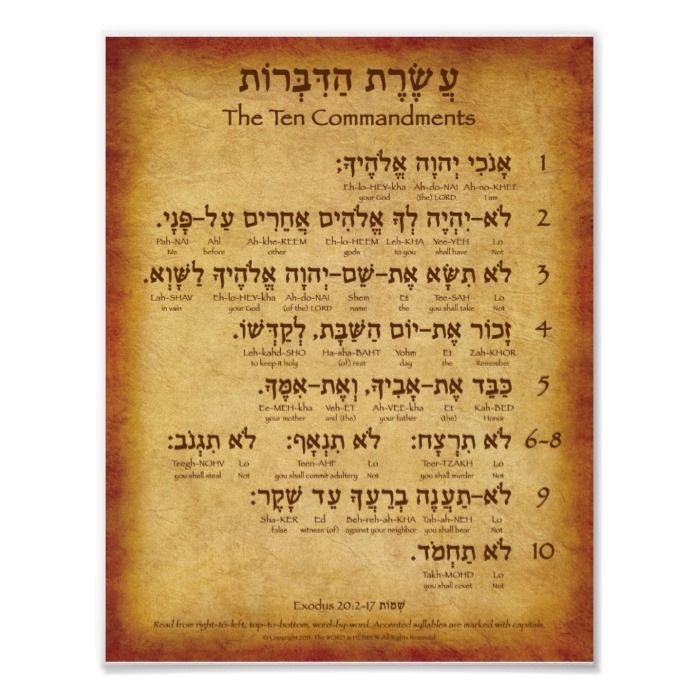

1. The description of these commandments. In Judaism, this collection of ten commands is known as the Aseret ha-Dibrot, a Hebrew phrase often translated by Jews today as “Ten Statements” or “Ten Declarations”. This is how this collection of “the words of the covenant” are described at Exod 34:28 (and again at Deut 4:13; 10:4). The second word in that phrase is simply “word”—so we might well think of these ten statements as “Ten Words” spoken by God to provide guidance and instruction to the Israelites.

2. The two versions of these Ten Words. The first version of these words is what we have in Exodus 20. (The lectionary edits the selection offered, omitting verses 5–6 and 10–11, to shorten some of the longer parts.) The second version appears in Deuteronomy 5. There are many similarities between the two versions, although the Deut 5 version is longer. One noteworthy difference is the instruction relating to the sabbath; “remember the sabbath day” (Exod 20:8), contrasted with “observe the sabbath day” (Deut 5:12). The difference in the verb is a just slight nuance of difference.

3. Two tablets of stone. Moses is given “two tablets of stone” by God, who informs him that they contain “the law (torah) and the commandment (mitsvah), which I have written for their instruction (horotam, from yara)” (24:12). The Hebrew words used here are part of a larger group of terms which describe all the instructions given throughout the first five books of scripture, the Torah. These tablets are later described as having been written “by the finger of God” (31:8), noting also that “the tablets were the work of God, and the writing was the writing of God, engraved upon the tablets” (32:6).

These two tablets are the ones that are notoriously broken by Moses in his anger when he discovers that the Israelites, in his absence, had made an image of a golden calf (32:19). This leads to the production of a replacement set of stone tablets, which Moses himself wrote under God’s instructions (34:1–4, 28).

These two tablets have most likely influenced the interpretation of the Ten Words as comprising one set of words in which the orientation is towards God (“you shall have no other gods … you shall not make an idol … you shall not make wrongful use of the name of the Lord your God … remember the sabbath day”, 20:2–11) and a second set oriented towards other humans (“honour your father and your mother, you shall not murder, you shall not commit adultery, you shall not steal, you shall not bear false witness against your neighbour, [and] you shall not covet”, 10:12–17). This, in turn, may have been an influence on the later rabbinic exposition (taken up by Jesus) of the Law as requiring love of God and love of neighbour (see Mark 12:28–31 and parallels).

4. How many laws do we have to remember? The natural desire to summarise and synthesise long lists into shorter, more readily remembered lists, may well account for the desire, in this encounter between Jesus and the scribe, to reduce all the commands to two. But there were other aspects involved in this process.

The Rabbis observed that the Torah, the first five books of scripture, actually contain 613 commandments (mitzvoth). There are 248 positive commands (“you shall …”) and 365 negative commands, or prohibitions (“you shall not …”). Collectively, these are known as mitzvoth, commandments; they comprise the Torah, the Law. In strict Jewish households, every one of them must be carefully observed.

However, the Babylonian Talmud (b. Makkoth 23b—24a) reports a rabbinic sermon in which various texts were cited in an attempt to make it easier to remember the central principles of the Torah. Rabbi Simlai declared that David reduced the 613 laws to eleven, citing Psalm 15. After him, Isaiah came, and found the basis in six commandments, quoting Isaiah 35:15-16.

Then the famous Micah triplet is cited, involving just three laws, “do justice, love kindness, walk humbly with your God” (Micah 6:8); before a later section of Isaiah is cited, noting that it proposed just two laws, “maintain justice, and do what is right” (Isa 56:1). Finally, Rabbi Simlai said there was an even shorter way to remember all the laws, and he cited Amos 5:4 as a single command: “seek me and live”.

Rabbi Nahman bar Isaac, however, proposed another prophetic text which provides one statement that summarises the Torah: “the righteous person lives by their faith” (Hab 2:4). This verse, of course, is familiar to Christians from Paul’s citation of it at Rom 1:17 and Gal 3:11.

Another way to summarise the Law is offered by the story of Rabbi Hillel, who is approached by a Gentiles seeking to convert to Judaism. Hillel says to the enquirer, “What is hateful to you, do not do to your neighbor. That is the whole Torah; the rest is the explanation of this—go and study it!” (b.Shabbat 31a). In like manner, when he was asked “which commandment is the most important of all?” (Mark 12:28), Jesus replies by citing two simple words: to love God (Deut 6:5) and to love neighbour (Lev 19:18).

5. Reading these words regularly. The Ten Words are read in full three times each year in Jewish synagogues. Jews follow a one-year lectionary, in which every verse in the first five books of scripture (the Torah, or the Five Books of Moses) is read in sabbath service during the course of the year. The weekly readings (called parashot, or “portions”) begin with Gen 1 and conclude with Deut 34. (The Jewish calendar follows the lunar cycle, and so it has 12 months of 29 or 30 days each, with an extra month added seven times every nineteen years. It’s complicated!)

So the Exodus passage is heard in the week when Exod 18:1—20:23 is read; and later in the year, the Deuteronomy version is heard, when Deut 3:23—7:11 is read. The Ten Words are also read at the Feast of Shavuot, which in the Jewish cycle of festivals is when the giving of the Law (the Ten Words) is remembered.

6. Quoted in the New Testament. The various commandments of these Ten Words are quoted in assorted New Testament passages. Jesus, in Matthew’s Gospel, affirms that all of the Law holds good; he comes to fulfil, not abolish, the Law (Matt 5:17). In the Sermon on the Mount, he specifically interprets—and intensifies—commands relating to murder and adultery, as well as not using God’s name in vain (Matt 5: 21–37).

Elsewhere in this Gospel, Jesus reinforces the importance of honouring parents (Matt 15:14) and of keeping this and further Words (murder, adultery, stealing, and lying, Matt 19:18). Paul likewise affirms that “the one who loves another has fulfilled the law” and “love is the fulfilling of the law” (Rom 13:8–10). In that passage, he cites four of the Ten Words (those relating to adultery, murder, stealing, and covetousness).

Earlier in the letter, he has referred to those words relating to stealing, adultery, and idol worship (Rom 2:21–22). Worshipping God, the first Word, is commended at Matt 4:10 and Luke 4:8; avoiding idol worship is advocated in the letter of the Jerusalem Church (Acts 15:20) and by Paul (1 Cor 6:9–10). The Sabbath is kept by Jesus (Luke 4:16) and Paul (Acts 17:2), as well as at Heb 4:9. Covetousness is condemned by Jesus (Luke 12:15) and Paul (Rom 7:7–11). So all ten of these Ten Words are affirmed in the New Testament—some on a number of occasions.

7. Numbering the list of ten. Judaism, unlike Catholicism and Protestantism, considers “I am the Lord, your God” to be the first “commandment”. Catholicism, unlike Judaism and Protestantism, considers coveting property to be separate from coveting a spouse. Protestantism, unlike Judaism and Catholicism, considers the prohibition against idolatry to be separate from the prohibition against worshipping other gods. No two religions agree on a single way to divide this stream of words into a list of ten distinct commands. So whose list should we follow?

8. Torah as a gift. To the Israelites of the past, as well as to Jews of today, the Torah is experienced as a gift which enriches their lives, not as a crass demand which weighs them down. The relationship that the people of Israel had with God was signalled in the Covenant that is offered to them. Exodus reports that the Lord spoke to Moses, “if you obey my voice and keep my covenant, you shall be my treasured possession out of all the peoples—indeed, the whole earth is mine, but you shall be for me a priestly kingdom and a holy nation” (Exod 19:5–6).

The Covenant is an outworking of this deep and abiding relationship between God and God’s people. That Covenant was not an idealised or abstract idea; it was known and expressed in each of the 613 laws contained within the Hebrew Scriptures. So the Law was considered to be a gift to the people, to be celebrated and valued as much as to be kept (Ps 19:7–11, 40:8, 119:97–104, 169–176). These Ten Words thus play a vital role in the shaping of society so that we live in ways that keep us in covenant relationship with God.

9. The basis of ethics. The Ten Words have formed a solid foundation for ethical principles, not just in Judaism and Christianity, but in wider societies more generally. During the early centuries of the church, these commandments are referenced in various documents, including the second century Didache, and they came to occupy their place in the developing catechism of the church, as Augustine of Hippo indicates in his Questions on Exodus.

The medieval scholastic, Thomas Aquinas, declared in his Summa Theologiae that these commandments provided “the primary precepts of justice and all law, and natural reason gives immediate assent to them as being plainly evident principles”. In his Institutes of the Christian Faith, Jean Calvin provides a detailed consideration of the Ten Commandments. He writes that “God has so depicted his character in the law that if any man [sic.] carries out in deeds whatever is enjoined there, he will express the image of God, as it were in his own life … it would be therefore a mistake for anyone to believe that the law teaches nothing but some rudiments and preliminaries of righteousness by which men [sic.] begin their apprenticeship, and does not also guide them to the true goal, good works.”

Their influence continues into 21st century societies across the globe. Writing in the Desert News (a conservative LDS publication), Paul Edwards proposes that “as long as people yearn for a cohesive and cooperative society that supports familial ties, secures the integrity of personhood and property, shuns petty jealousies and violence, and seeks to treat all alike in the eyes of social authority and before God, then the Ten Commandments — which accomplish these and much more — will continue to be inescapably relevant.”

10. The last word on the Ten Words relates to the last of these ten commandments. It is a curiosity not often commented on—but this last command indicates that these words are directed towards the males in the community, not to everyone, males and females alike. The final command specifies that a person “shall not covet your neighbour’s wife”, and the wording used clearly indicates that these words are directed towards males. It doesn’t say, “you shall not covet your neighbor’s husband”—which is the first indication that the instruction is directed towards men.

Further, we might note that Hebrew is a language in which gender can be indicated in the choice of words; and in this instance, every time the possessive pronoun “your” appears in this commandment, each of those possessive pronouns are masculine. It is your (male) neighbour’s house, your (male) neighbour’s wife, your (male) neighbour’s slave or ox or donkey, or anything that belongs to your (male) neighbour.

And it is noteworthy that there are feminine words used in this commandment (wife and maidservant), so the distinction is being drawn with intention and care. It is the male who possesses house and male slave and ox and donkey, as well as female slave and wife—all are possessions of the male. Which is only to be expected in the patriarchal culture in which these commandments were articulated.

And so, as we hear these Ten Words this coming Sunday, there are many things for us to reflect on!

See also