There have been a number of posts on my Facebook feed in recent weeks, on the matter of Hell. A number of them have made the claim that Hell does not appear in the New Testament. It’s a common claim made by hardline “progressive” Christians. The Gospel passage proposed by the Revised Common Lectionary for this coming Sunday (Matt 25:14–30) would suggest otherwise, however.

This passage offers a parable of Jesus (found here and, in another version, in Luke 19), in which two slaves are commended for their shrewd stewardship of a huge amount of money that was entrusted to them, whilst one slave is punished for not improving the amount he was given.

In Luke’s version, the third slave is called “wicked” (Luke 19:22) and the money he was given is taken from him and given to the first slave, to illustrate the saying, “to all those who have, more will be given; but from those who have nothing, even what they have will be taken away” (Luke 19:24–26). In Matthew’s version of this this parable, the slave is called “wicked and lazy” Matt 25:26) as well as “worthless”, and his punishment is far more severe: he is to be thrown “into the outer darkness” (25:30).

This is the third reference by the Matthean Jesus to “outer darkness” (8:12; 22:13; 25:30). As the parable that follows refers to “the eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels” (25:41)—to which Jesus had earlier referred (18:8)—it does seem that Jesus is referring to a place that we know by the term “hell”. Indeed, words spoken by Jesus in Matt 18:9 are rendered explicitly as “the hell of fire” in the NRSV, while the NIV renders this “the fire of hell”. They are both translating a Hebrew word, here transliterated into Greek, Gehenna (on which, see more, below).

Over the years I have had a number of interesting conversations about these passages, and others, and about “hell” in biblical texts, with my wife, Elizabeth Raine, as she has studied both Matthew’s Gospel (where there is a preponderance of passages referring, in one way or another, to “hell”), as well as the relevant Hebrew Scripture passages often linked with “hell”, so what follows is strongly informed by those conversations.

Now, my search of the NRSV indicates that the word “hell” does appear 13 times in this translation of the New Testament. 11 of these are in the Synoptic Gospels, each time in words attributed to Jesus (the other two are in James and 2 Peter). The NIV has the same 13 occurrences of the word “hell”; but in the 17th century translation authorised by King James, the word appears 23 times in the New Testament (15 of these in the Synoptics) as well as 31 times in the Old Testament. Clearly, the reticence to use this word in translating relevant Hebrew or Greek words grew between the 17th and the 20th century. Why might that have been?

I think that this reticence might relate, in part, to a developing clarity about what the various words in Hebrew and Greek actually described. Rather than lumping them all together under the catch-all term “hell”, more recent translators take care to provide more distinctive descriptors.

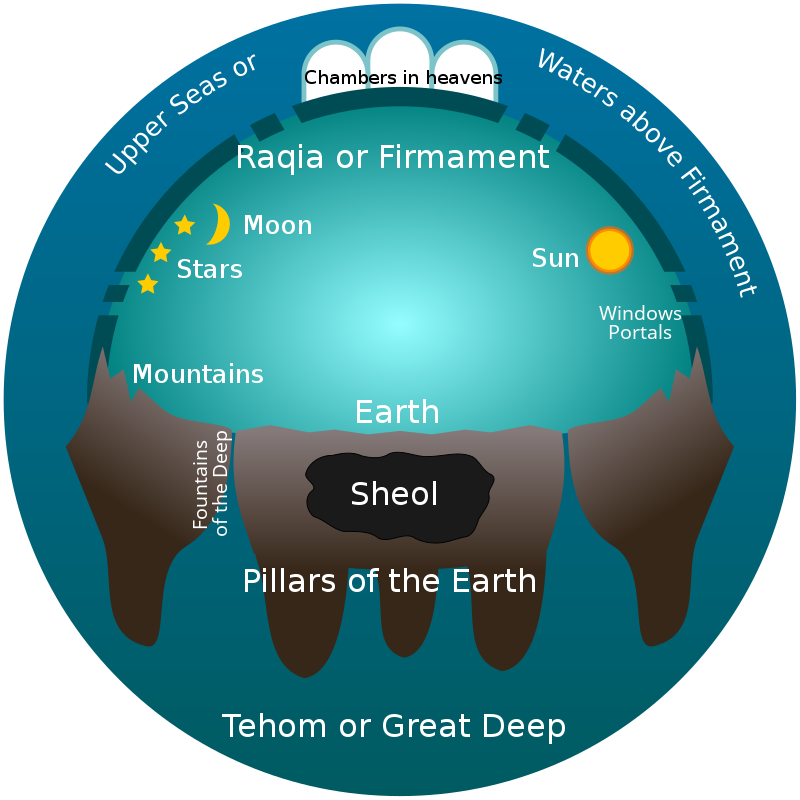

There are a number of concepts which need to be considered. This takes us into the strange world of ancient Hebrew cosmology—the world, heavens and earth, what was above and what was below, was understood in a different way from the way that 21st century people understand such things.

In Hebrew Scripture, there are references to the Deep, the Pit, and Sheol. These three words appear to describe the state of being of human beings after they have died. In the King James Version, the word “hell” is used to translate these Hebrew words on quite a number of occasions. But we need to explore them more carefully.

Sheol is the opposite of heaven in spatial terms; as heaven is in the heights, so Sheol is in the depths. (Gen 49:25). Isaiah says that God invited King Ahaz to “ask a sign of the Lord your God; let it be deep as Sheol or high as heaven” (Isa 7:11; the sign that is then given is the famous child, to be named Immanuel, 7:14). Ezekiel describes the demise of “Assyria, a cedar of Lebanon … [that] towered high and set its top among the clouds” in these words from God: “on the day it went down to Sheol I closed the deep over it and covered it” (Ezek 31:15). In this fate, it shared with those who “are handed over to death, to the world below … with those who go down to the Pit” (Ezek 31:14).

The terms found here—Sheol, the Deep, the Pit, the world below—are part of a cluster of terms which appear throughout Hebrew Scripture. Technically, The Deep describes the waters of chaos, outside the Dome, which can rise up to flood the world, as in the story of Noah, when in one version “all the fountains of the great deep burst forth, and the windows of the heavens were opened” (Gen 7:11) and, after 150 days, “God made a wind blow over the earth, and the waters subsided; the fountains of the deep and the windows of the heavens were closed, the rain from the heavens was restrained, and the waters gradually receded from the earth” (Gen 8:2).

Sheol and The Pit each describe the state of the nephesh (the essence of being) of those whose bodies have died. In Psalm 88, when the psalmist laments “my soul is full of troubles”, they use these and other terms in poetic parallelism to describe their fate: “my life draws near to Sheol; I am counted among those who go down to the Pit; I am like those who have no help, like those forsaken among the dead, like the slain that lie in the grave, like those whom you remember no more, for they are cut off from your hand; you have put me in the depths of the Pit, in the regions dark and deep” (Ps 88:3–6). Another psalm describes this as “the land of silence” (Ps 94:17), while the prophet Ezekiel imagines it as the place where the dead, the “people of long ago” lie “among primeval ruins” (Ezek 26:20)

In this state, people simply lie in darkness, not living, with no future in view, no hope in store. Job laments, “if I look for Sheol as my house, if I spread my couch in darkness, if I say to the Pit, ‘You are my father,’ and to the worm, ‘My mother,’ or ‘My sister,’ where then is my hope?” (Job 17:13-15). Job also equates entering the Pit with “traversing the River” (Job 33:18), in words that seem to reflect the River Hubur (in Sumerian cosmology) or the River Styx (in Greek cosmology), the place where the souls of the dead cross over into the netherworld.

Other words for Sheol in Hebrew Scripture include Abaddon, meaning ruin (Ps 88:11; Job 28:22; Prov 15:11) and Shakhat, meaning corruption (Isa 38:17; Ezek 28:8). These terms indicate the forlorn, lost, irretrievable nature of this state of being. This is the fate in store for all human beings, whether righteous or wicked; there is no sense of judgement or punishment associated with this state. It is simply a state of non-being.

By the time of the New Testament, however, there had been quite some development in this direction within Jewish thinking. In the apocalyptic visions of 2 Esdras, Ezra is depicted as foreseeing that “the pit of torment shall appear, and opposite it shall be the place of rest; and the furnace of hell shall be disclosed, and opposite it the paradise of delight” (2 Esd 7:36).

Likewise, the seven Maccabean brothers tell “the tyrant Antiochus” that “justice has laid up for you intense and eternal fire and tortures, and these throughout all time will never let you go” (4 Macc 9:9; also 12:12). In the teaching contained in the Wisdom of Solomon, however, a complementary element is noted, as Solomon is said to declare “the souls of the righteous are in the hand of God, and no torment will ever touch them” (Wisd Sol 3:1).

The New Testament—largely in the Synoptic Gospels, but also in Revelation—reflects these developments in the way that it portrays the afterlife, with a number of sayings portraying a place of punishment for sinners after death, as well as the promise of eternal life for the righteous with God in the kingdom of heaven.

There are three Greek words that are relevant at this point: Gehenna, Hades, and Tartarus. The first, Gehenna, was a geographical term, referring to the Valley of Hinnom, to the southwest of Jerusalem, where in periods of sinfulness before the Exile, children had been sacrificed to Molech (2 Ki 23:10; 2 Chron 28:3; 33:6; Jer 7:31-32; 32:35). This practice was the cause of punishments experienced by the people for their sinful behaviour.

Gehenna appears twelve times in the New Testament—eleven of those being in words attributed to Jesus (Mark 9:43, 45, 47, paralleled in Matt 18:9; Matt 5:22, 29, 30; 10:28; 23:15, 33; and Luke 12:5). In some of these occurrences, Gehenna is placed into parallel with other ideas which suggest it is no longer the simple geographical reference of Hebrew Scripture texts, but it has become a place of punishment for sinners in the afterlife (see further below).

The potency of Gehenna is noted when James warns those who misuse their tongue as “a restless evil, full of deadly poison” (James 3:8) that “the tongue is placed among our members as a world of iniquity; it stains the whole body, sets on fire the cycle of nature, and is itself set on fire by hell [translating the Greek Gehenna]” (James 3:6).

A second word, found ten times in the New Testament, is Hades; a word adopted from older Greek literature, where it appears from Homer onwards as the name of the God of the lower regions (Hades, later Pluto, the brother of Zeus and Poseidon) and of the realm of the dead. This was where all people went after their death; leaving Hades was not possible (with the exception of a few heroic figures in the myths of the Greeks).

Jesus speaks of going down to Hades (Matt 11:23; Luke 10:15); perhaps he himself went there? (1 Pet 3:19 may allude to this). The deceased rich man in Hades looks up to heaven to see the poor man, Lazarus, with Abraham (Luke 16:22–23). Hades in this parable is a place of torment (Luke 16:23, 25); the rich man endures punishment which apparently cannot be revoked (Luke 16:26).

In Acts, Peter is said to have quoted Ps 16:10, referring to the soul being abandoned in Hades, in his speech at Pentecost (Acts 2:27, 31), and four times in Revelation Hades is linked with death (Rev 1:18; 6:8; 20:13–14). The Matthean Jesus informs Peter that “the gates of Hades will not prevail” against the church, founded in Peter, the rock (Matt 16:18). Hades has gates, presumably to ensure its inhabitants cannot escape the fate determined for them.

It is interesting that for a number of verses in the Septuagint, the Greek word Hades translates Sheol, thereby turning it from a Hebrew idea into a Greek concept for the hellenised Jewish readers of the Septuagint.

The introduction of punitive elements into the way that Gehenna and Hades are described leads to a third Greek word which is relevant to our considerations. The Greek noun is Tartarus, which the Encyclopedia Britannica explains in this way: “the name was originally used for the deepest region of the world, the lower of the two parts of the underworld, where the gods locked up their enemies. It gradually came to mean the entire underworld. As such it was the opposite of Elysium, where happy souls lived after death.” See https://www.britannica.com/topic/Tartarus

Whilst that name itself does not appear in the New Testament, the cognate verb tartaróō is found once, in the very late and pseudonymous epistle, 2 Pet 2:4. It is translated as “to cast down to hell” in the KJV and in most recent modern translations, where it describes what God did to sinful angels, demonstrating that “the Lord knows how to rescue the godly from trial, and to keep the unrighteous under punishment until the day of judgment —especially those who indulge their flesh in depraved lust, and who despise authority” (2 Pet 2:9–10). So be warned!

All of which indicates that notions of Hell as a place in the afterlife where sinful people are sent, to experience divine punishment, are alive and well at the time the various New Testament books were written.

And so: what of the parable that Jesus tells (Matt 25:14–30) ??

… to be continued …

*****

With thanks to Elizabeth Raine for insights about relevant texts at many places through this discussion.