As we start a new year in the church’s calendar, this coming Sunday we will enter into the season of Advent, and begin our preparations once more for Christmas—the coming of Jesus, Saviour, chosen one, and Lord (Luke 2:11). During Advent, the lectionary offers a selection of biblical passages designed to help us in our preparations, building to the climactic moment of Christmas Day, when we remember that “the Word became flesh and lived among us, and we have seen his glory, the glory as of a father’s only son, full of grace and truth” (John 1:14).

These scripture passages include a sequence of excerpts from the Hebrew Scriptures—largely from the book of Isaiah—which orient us to the saving work of God, experienced by faithful people in Israel through the ages. These scripture passages lead us along a path that brings us to the point when we can sense God’s work in the story of Jesus.

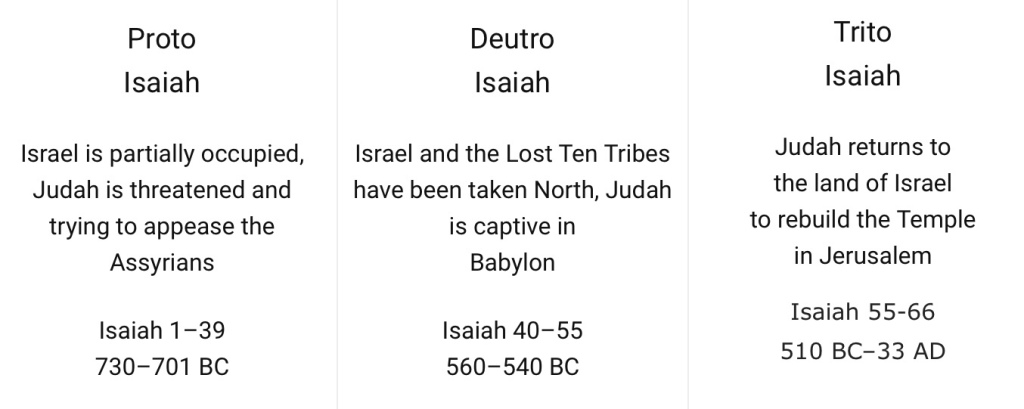

The book of Isaiah comprises three sections, which most scholars believe originated in three different periods during the history of Israel. The first section (chs. 1–39) is located in Judah in the eighth century BCE, as the Assyrians conquered the northern kingdom of Israel and attempted to gain control of the southern kingdom, but that effort failed. These events provide the context for the activity of Isaiah and the oracles include in chapters 1–39.

The second section of Isaiah (chs. 40–55) dates from the time of exile for the southern kingdom, after the people of Judah had been conquered by the Babylonians in 587 BCE; it offers words of hope as the people look to a return to the land. Then, the third section (chs. 56–66) is dated to a time when the exiles had returned to Judah, sometime after 520 BCE. By convention, the three parts are known as First Isaiah, Second Isaiah, and Third Isaiah.

For Advent 1, the lectionary offers us a passage from that final section, Third Isaiah, with words from the post-exilic prophet, “O that you would tear open the heavens and come down, so that the mountains would quake at your presence” (Isa 64:1). Echoing the apocalyptic words of Jesus in the Gospel passage for this Sunday (Mark 13), the prophet foreshadows the rending of the heavens that will occur when God steps into earthly life in Jesus of Nazareth.

Then from the very familiar passage that opens Second Isaiah, as the prophet looks to the end of the exile, on Advent 2 we hear the promise that “the Lord God comes with might … he will feed his flock like a shepherd; he will gather the lambs in his arms, and carry them in his bosom, and gently lead the mother sheep” (Isa 40:10–11). Words of comfort for the exiles; words which Christian interpreters see as a depiction of the shepherding role that Jesus undertakes.

On Advent 3 we return to the third section of Isaiah, to hear another set of very familiar words, which Luke tells us that Jesus appropriated (Luke 4:16–21) to describe his own mission in Israel: “the spirit of the Lord God is upon me, because the Lord has anointed me; he has sent me … to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favour” (Isa 61:1–2).

Then, on Advent 4, we move away from Isaiah to hear the narrative account in which the prophet Nathan tells King David that God has told him, “your house and your kingdom shall be made sure forever before me; your throne shall be established forever” (2 Sam 7:16). These are words which throughout the centuries since Jesus have been seen by Christians as applicable to his God-appointed role.

After this, for Christmas itself, we hear a selection of passages from Isaiah—one from each of the three sections of the book—which also have been seen by Christian interpreters to connect with the story of Jesus: “a child has been born for us, a son given to us; authority rests upon his shoulders; and he is named Wonderful Counselor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace” (Isa 9:6); “the Lord has proclaimed to the end of the earth: Say to daughter Zion, ‘See, your salvation comes; his reward is with him, and his recompense before him’” (Isa 62:11); and then, most strikingly, “all the ends of the earth shall see the salvation of our God” (Isa 52:10).

In the passage from Isaiah 64, the prophet is clear and direct. “Tear open the heavens” (v.1a), he implores God, shouting with the passionate intensity of one who fervently desires a clear sign of the presence of the divine. “Come down, so that the mountains would quake at your presence”, he cries (v.1b). After all the devastation that Israel has experienced (vv.6–7, 10–11), the psalmist yearns for God to act, just as God did “when you did awesome deeds that we did not expect, you came down, the mountains quaked at your presence” (v.3).

The various tribulations of the people of Israel, from their testings in the wilderness through to the Exile, when they had been “burned with fire … cut down” (v.16), are seen as multiple punishments heaped onto Israel. So the psalmist implores God, “do not be exceedingly angry, O Lord, and do not remember iniquity forever” (v.9), and pleads to God, “will you restrain yourself, O Lord? Will you keep silent, and punish us so severely?” (v.12).

The tone is much like the psalms where the writer pleads for God to act, for mercy to be shown. “O God, you have rejected us, broken our defenses; you have been angry; now restore us!” is the plea in one psalm (Ps 60:1). In another, the psalmist laments, “How long, O Lord? Will you be angry forever? Will your jealous wrath burn like fire?” (Ps 79:5); we hear similar words as the psalmist elsewhere asks, “Will you be angry with us forever? Will you prolong your anger to all generations?” (Ps 85:5).

Perhaps most vivid of all, and closest to the thoughts that the prophet declares, is this psalm: “Bow your heavens, O Lord, and come down; touch the mountains so that they smoke. Make the lightning flash and scatter them; send out your arrows and rout them. Stretch out your hand from on high; set me free and rescue me from the mighty waters, from the hand of aliens, whose mouths speak lies, and whose right hands are false.” (Ps 144:5–8)

The action of tearing is something that is dramatic and final. It damages permanently. The prophet Hosea describes this vividly in his account of how God plans to respond to Ephraim, when they “keep on sinning and make a cast image for themselves”; God’s intention is, “I will fall upon them like a bear robbed of her cubs, and will tear open the covering of their heart; there I will devour them like a lion, as a wild animal would mangle them” (Hos 13:8).

The language of “tearing” is used to describe the punishment that God will bring upon sinful Israel. Solomon is told, “since you have not kept my covenant and my statutes that I have commanded you, I will surely tear the kingdom from you and give it to your servant” (1 Ki 11:11). That threat is reflected also in psalms (Ps 52:5; 137:7–8) and prophecies (Jer 22:24–27; and cf. Amos 3:15). But the orientation of tearing in this prophecy is not about punishing Israel—rather, the psalmist, as we have seen, is imploring God to come, end the punishment of Israel, and “not remember iniquity forever” (Isa 64:9).

Tearing clothes in an act of mourning is reflected at times in scripture (2 Sam 3:31; Esther 4:1). But this seems far from the intent of this passage, which is focussed on seeking a sign of the presence of God, “so that the nations might tremble at your presence” (Isa 64:2) and so that God might “meet those who gladly do right, those who remember you in your ways” (Isa 64:5).

For Christian interpreters, however, when the prophet speaks of God tearing open the heavens in order that God might “come down” (from heaven, to earth), the clearest resonance lies elsewhere. Much is made of the connection with the moment when the curtain of the Temple was torn “from top to bottom” (Mark 15:38; Matt 27:51; Luke 23:45) at the death of Jesus. God dramatically tore apart the curtain that kept the priests from seeing the Holy of Holies, where God resided (Exod 26:33; Heb 9:3) and came down “from top to bottom”, from heaven to earth, in Jesus (cf. John 6:41, 51, 58; Phil 2:5–8).

And so a Christian appropriation of this passage may well appreciate the symbolism of God overcoming the division between heaven and earth in this way. And Christian interpreters may well go on to appropriate other phrases in this prophecy of Isa 64 as relating to Jesus, for in his life, they might affirm, God has done awesome deeds (v.3), has met “those who gladly do right” (v.5), who has reshaped sinners as the potter fashions the clay (v.8), who forgives iniquity (v.9), who acts as the only God ever known (v.4).

That said, we should caution that interpreting this passage and other ancient Israelite prophetic passages as predictive of Jesus is a strategy that we should undertake with care. Christians have a bad track record of taking Jewish texts and Christianising them, talking and writing and thinking about them as if they were always intended simply to be understood as Christian texts. But first of all, they were Jewish (or, to be precise, ancient Israelite) texts.

So the original setting of such passages needs always to be considered—the historical, social, political, cultural contexts in which they came into being, as well as the literary genre being used and the linguistic and literary conventions being deployed. Obliterating the original setting and acting as if the text was intended for a time many centuries later, is unfair and unethical.

Indeed, Christianising Old Testament texts can well become the first step in a dangerous process, as we firstly remove Judaism from our interpretive framework, and then treat the prophetic text as having nothing to do with Judaism, and everything to do with Christianity. This is the pathway that can lead to antisemitism—actively speaking and acting against Jews and Judaism. And having arrived at such a destination, we are reinforced in our pattern of ignoring and obliterating the earlier meanings in the text.

Texts (whether biblical or other literature) are always multivalent—that is, open to being interpreted in a number of ways, offering multiple ways of understanding them. That’s why we have sermons, and don’t just read the biblical text and then put it down. We keep it before our minds, and explore options for understanding and appropriating it. Ignoring the multiple layers of meaning inherent in biblical passages is a reductionist and self-centred way of undertaking interpretation. Reducing the prophetic texts to predictive declarations solely about Jesus is a poor interpretive process.

So let us tread with caution, this Advent, and beyond, as we hear, savour, and interpret texts from these ancient Israelite works—in which, nevertheless, we can indeed hear “the word of God” to us, in this day.