During this season of Advent, the lectionary offers a selection of biblical passages designed to help us in our preparations, building to the climactic moment of Christmas Day, when we remember that “the Word became flesh and lived among us, and we have seen his glory, the glory as of a father’s only son, full of grace and truth” (John 1:14).

These scripture passages have include a sequence of excerpts from the Hebrew Scriptures—largely from the book of Isaiah—which orient us to the saving work of God, experienced by faithful people in Israel through the ages. These scripture passages inform us as to how God might be understood to be at work in the story of Jesus. For my part, I don’t read these Hebrew Scripture passages as “predictions” pointing to Jesus. Rather, I consider that the prophets and psalmists of ancient times were addressing their own situations, not peering into the distant future.

How I read these passages is not in a simplistic prophecy—fulfilment pattern. That is too crass, and it pays no respect at all to the wisdom of faithful people in ancient Israel. Rather, I read these passages as testimonies to the way that faithful people of old understood and experienced God to be at work in their own times, in their own lives. What they wrote—the word of the Lord for their own time—has been repeated and remembered, retold by word of mouth and written onto scrolls which, over time have become recognised as important, influential, even inspired words of wisdom.

So whilst the Hebrew Scripture passages tell us of how God had been at work in years past, they are retained as relevant words which provide guidance and direction for understanding how God would presumably be at work in later times, in the times of Jesus, and indeed in our own times today. When we read and hear and ponder these ancient words, we are opening our hearts and minds to the guidance of God’s Spirit, instructing us in our lives of faith today.

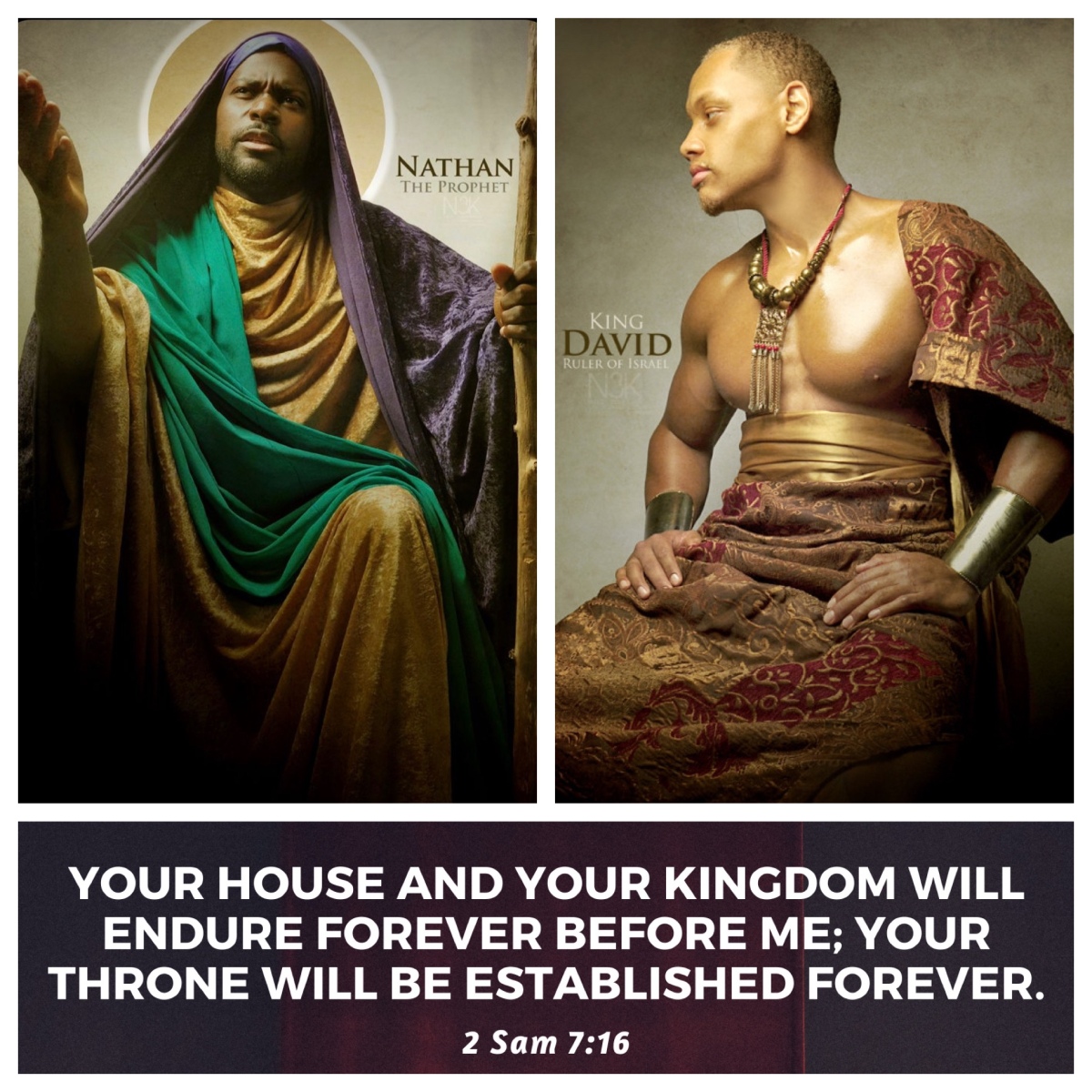

For the fourth Sunday in Advent, we are offered a well-known passage from 2 Samuel; the message that the prophet Nathan receives from the Lord God, which he is instructed to convey to King David (2 Sam 7:1–11, 16). Curiously, the lectionary omits the final comment of the narrator, “in accordance with all these words and with all this vision, Nathan spoke to David” (2 Sam 7:17).

It is worth understanding where this passage comes in the narrative flow of events, for it occurs at a critical time in the story of the people of Israel. In earlier chapters, the prophet Samuel had (somewhat reluctantly) anointed Saul as king in Israel (1 Sam 10:1). This was done in obedience to a direct word of the Lord to Samuel: “I will send to you a man from the land of Benjamin, and you shall anoint him to be ruler over my people Israel. He shall save my people from the hand of the Philistines; for I have seen the suffering of my people, because their outcry has come to me.” (1 Sam 9:16).

However, in the midst of his battles with the Philistines, Saul eventually kills himself, when he sees how hopeless the situation has become (1 Sam 31). The early chapters of 2 Samuel recount the antagonism and chaos of the ensuing days, as “the people of Judah … anointed David king over the house of Judah” (2 Sam 2:4). However, “there was a long war between the house of Saul and the house of David”; during the course of this war “David grew stronger and stronger, while the we Bw ww c house of Saul and and became weaker and weaker” (2 Sam 3:1).

At this point in the story, David recognises an incongruity: “I am living in a house of cedar, but the ark of God stays in a tent”, he tells Nathan (2 Sam 7:2). The implication is that David is now about to redeploy the carpenters and masons whom King Hiram of Tyre had earlier provided for him to build his own house (2 Sam 5:11), and commission them now to build a house for God to live in (2 Sam 7:5).

So the Lord God directs the prophet Nathan to intervene, reminding him that “I have not lived in a house since the day I brought up the people of Israel from Egypt to this day, but I have been moving about in a tent and a tabernacle” (2 Sam 7:6). Samuel is to inform David that God does not need a house to be built for his residence. Rather, God will create a “house” for David; but that house will not be a cedar lodge of multiple rooms, but a royal dynasty with a lineage of monarchs.

The wordplay on “house” is at the heart of this passage. In Hebrew, the word bayith can equally refer to a structure built for people to live in, or to a collection of people living together as a household or related as a family group. That is the same as the English word “house”, which can refer to a domestic structure or a family group. While David yearns to build a structure to house the Lord God—a temple—the intentions of God for David are rather that he will build a family—a dynasty—which will ensure the security of the nation in future generations.

God promises David that he will make him the first in a line of men to rule over Israel—indeed, God promises that “I will establish the throne of his kingdom forever” (2 Sam 7:13). So confident is the Lord God about this promise that he repays it; “your house and your kingdom shall be made sure forever before me; your throne shall be established forever” (7:16).

I think the thrice-repeated claim “forever” is hyperbolic grandstanding; the united kingdom that David inherited from Saul and bequeathed to Solomon did not last “forever”. In less than a century, the kingdom was divided; in another two centuries, the northern kingdom had been defeated and there were no rulers in the line of David, and within another one-and-a-half centuries the southern kingdom had met the same fate.

Later generations would cling to that promise and interpret it in various ways. The narrator of 1–2 Samuel and 1–2 Kings tells of the continuation of this promise over the centuries. Whoever edited the final version (sometime in the Exile, is the best guess) would have known that the promise did not actually last “forever”; yet they retained that claim in the narrative of 2 Sam 7. The promise had been made; even knowing that it was not carried through in history, that story still was to be told.

Various psalms follow suit, celebrating that God “shows steadfast love to his anointed, to David and his descendants forever” (Ps 18:50), bestowing blessings on David forever (Ps 21:6; 45:2), ensuring that “your throne, O God, endures forever and ever” (Ps 45:6), and offering prayers for the king, “may he be enthroned forever before God” (Ps 61:7), “may his name endure forever” (Ps 72:17).

Similarly, even whilst in exile, the prophet Jeremiah celebrates the promise that “David shall never lack a man to sit on the throne of the house of Israel” (Jer 33:17). However, as the prophet surveys “the towns of Judah and the streets of Jerusalem that are desolate, without inhabitants, human or animals” (Jer 33:10), he considers, at least fleetingly, the consequence that David “would not have a son to reign on his throne” (Jer 33:21).

(Nevertheless, the oracle ends with a reversion to the hope that God “will restore their fortunes, and will have mercy upon them”, v.26; earlier, Jeremiah had spoken of the “righteous Branch” who would “spring up for David”, v.15. Indeed, all the exilic prophets hold strongly to the hope of a restored and renewed kingdom.)

However, the definitive break of the line is clearly envisaged at the same time, during the exile, by one of the psalmists, in Psalm 89. Initially, in this psalm, the psalmist declares that “your steadfast love is established forever” (v.2), notes that God’s “hand shall always remain” with David (v.21), and affirms that “his line shall continue forever” (v.36).

And yet, that psalmist continues, “you have spurned and rejected him; you are full of wrath against your anointed” (v.38), “you have removed the scepter from his hand and hurled his throne to the ground” (v.44). The psalm ends with lament: “Lord, where is your steadfast love of old, which by your faithfulness you swore to David?” (v.49).

Clearly, “forever” did not mean for all time, in some aspects of the developing Jewish understanding. The period of exile was indeed the catalyst for consideration of how a Jewish nation might continue; from this time onwards, many Jews continued to practice their religion in the Diaspora, right through to the present. But their practices and customs changed, developed, adapted. And as the sages of the people grappled with ways to live out their faith in a healthy way in those dispersed contexts, they developed various reassessments of the previously strong links between the king, the covenant, and the Lord God. “Forever” did not mean “forever”.

And yet in Christianity, the promise was seen to be still valid; indeed, the Christian claim is that it was continuing in Jesus. The angel Gabriel tells the pregnant Mary that the child she will bear “will reign over the house of Jacob forever, and of his kingdom there will be no end” (Luke 1:33). The writer of the letter to the Hebrews quotes Psalm 45:6 and applies it directly to the Son: “your throne, O God, is forever and ever” (Heb 1:8), while the author of Revelation foresees that when the seventh angel blew his trumpet, “there were loud voices in heaven, saying, ‘The kingdom of the world has become the kingdom of our Lord

and of his Messiah, and he will reign forever and ever’” (Rev 11:15).

So the inclusion of this story in the readings for Advent 4 is, no doubt, because of the Christian understanding that Jesus stands in the line of David, as the shepherd of his sheep, and as the one who rules over the house of God in an eternal kingdom that will never end. (Quite uncharacteristically for me, I have here combined ideas from a number of biblical texts into one harmonised theological statement. This is what systematic theology often does.)

David, the shepherd boy, is anointed as King and designated as the head of a house that will provide leaders stretching into the future in a kingdom that will “be made sure forever before me” (2 Sam 7:16). Jesus is claimed to be of the house of David (Luke 1:27; Matt 1:20) and is acclaimed as “Son of David” (Mark 10:47–48; Matt 20:30–31; Luke 18:38–39), a title that is especially emphasised elsewhere in Matthew’s Gospel (Matt 9:27; 12:23; 15:22; 21:9, 15). The title, for Jewish hearers of those early Gospels, signals the belief that God is at work through this person, Jesus, to guide and lead the people of God.

This Hebrew Scripture passage, like others we have read and heard during Advent, thus orients us to the saving work of God, experienced by faithful people in Israel through the ages, which is later claimed by followers of Jesus to have been manifested in his life. For that reason, we hear it during this Advent season; not as a prophecy which was fulfilled by Jesus, but as a testimony to the ways of God which continue from aeons ago into the present time.