In this year of the lectionary, the focus is on the narrative offered by “the beginning of the good news of Jesus, Chosen One”, which we know as Mark’s Gospel. The author of this work plunges right in to the story from the very beginning. There is no preface, no prologue, no extended set up, like we have in other Gospels; just straight down to business. The various scenes in this opening chapter are offered in the revised common lectionary in Year B, largely during the season of Epiphany.

These scenes offer a snapshot of the key features of the lead character in the story that is told. That figure, Jesus of Nazareth, is intensely religious (Mark 1:9–11, 35), articulately focussed on his key message (1:14–15, 22, 39), building a movement of committed followers (1:16–20), regularly living out his faith in actions alongside his words (1:26, 31, 34, 39). Jesus is energised by personal contacts with individuals: the brothers whom he called (1:17, 20), the man in the synagogue (1:25), Simon’s mother-in-law (1:30–31), and a begging leper (1:40). In the midst of all of this, he makes sure that his central message (1:14–15) is conveyed with clarity and passion (1:27, 39, 45).

Jesus is nourished by quiet moments, in his wilderness testing (1:12–13) and in early morning prayer (1:35), and yet is consistently immersed in the public life of his community. The author most likely exaggerates, but he does indicate that Jesus was with “people from the whole Judean countryside and all the people of Jerusalem” (1:5), teaching a crowd in the synagogue in Capernaum (1:21), renowned “throughout the surrounding region of Galilee” (1:28).

The author also notes that Jesus is visited by “all who were sick or possessed with demons”, indeed by “the whole city” (1:32–33), told that “everyone is searching for you” (1:37), and touring throughout Galilee (1:39), where “people came to him from every quarter” (1:45). He is quite the drawcard!

It is an holistic portrayal of Jesus, setting the scene for the story that follows. Jesus is passionate and articulate, compassionate and caring, energised and engaged, focused on a strategy that will reap benefits as the story emerges. And yet, as we know, that passion and energy will also lead to conflict, suffering, and death; a conflict already depicted in some of these opening scenes, as the story commences, but soon to make its presence felt in full force as the narrative continues.

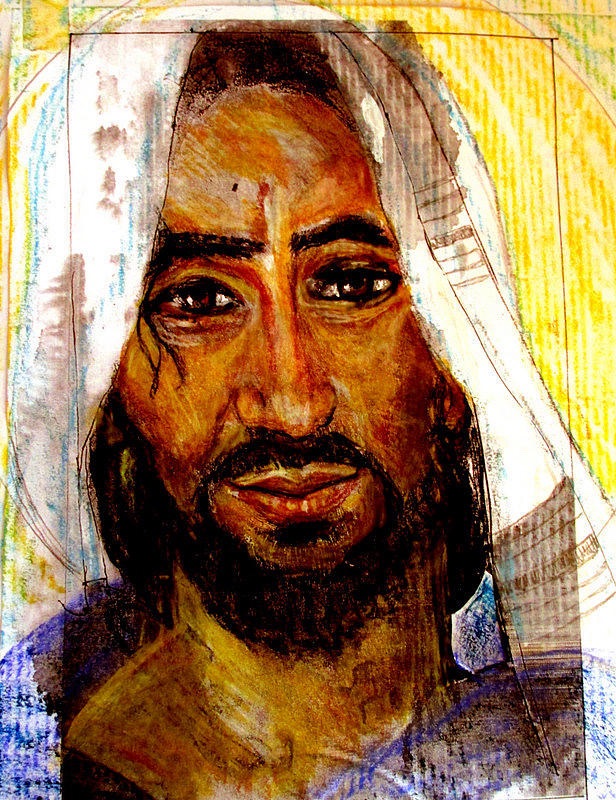

like Jesus, might well have appeared

The author of this narrative—known by tradition as “Mark”—begins this series of scenes with the striking moment when Jesus of Nazareth was declared to be the beloved Son, anointed by the Spirit, equipped for his role of proclaiming the kingdom of God (Mark 1:1–13), which we hear this coming Sunday when the focus is on the Baptism of Jesus.

We know that Jesus was raised as a good Jew. We can hypothesise much about his upbringing and faith. He knew the daily prayer of the Jews, the Shema (“Hear, O Israel, the Lord our God is One”). He also knew the major annual festivals of his people: Passover, Harvest (later called Pentecost) and Tabernacles.

Jesus attended the synagogue each Sabbath, where he watched the scrolls containing the Hebrew scriptures unrolled, before they were read (in Hebrew, the sacred language) and explained (in Aramaic, the language of the common Jewish folk). Jesus, like all his fellow–Jews, believed that his God, Yahweh, was the one true God. He followed the traditional practices of worship and studied the scriptures under the guidance of the scribes in his synagogue.

At a mature age (by tradition, in his early 30’s), Jesus made his way south towards Jerusalem, into the desert regions, along with other Jews of the day. Beside the Jordan River he listened to the preaching of a strange figure—a desert-dwelling apocalyptic prophet named John (Mark 1:4–8). This appears to have been a pivotal moment for the pious Jewish man from Nazareth. His encounter with John deepens his faith and sharpens his commitment.

John’s message was the traditional prophetic call to repent (1:4). Prophets occasionally call directly for teshuva (Hebrew; in Greek, metanoia). These words are usually translated into English as “repentance” (see Isa 1:27; Jer 8:4-7, 9:4-5, 34:15; Ezek 14:6, 18:30; Zech 1:1-6). Indeed, so many of the oracles included in both major and minor prophets provide extended diatribes against the sinfulness of Israel and call for a return to the ways of righteousness that are set out in the convening with the Lord. When prophets called for metanoia, repentance, they were seeking a striking and thoroughgoing change of mind, a reversal of thinking and acting, a 180 degree turnaround, amongst the people. This is what metanoia means.

Accompanying this, however, was a very distinctive action that John the desert dweller performed, of immersing people into the river (Mark 1:5). Our Bibles translate this as “baptising”, but it was actually a wholesale dunking right down deep into the waters of the river.

Our refined ecclesial terminology of “baptism” is often associated, in the popular mind, with cute babies in beautiful christening gowns surrounded by adoring grandparents, aunties and uncles. This leads us far away from the stark realities of the act: being pushed down deep into the river, being completely surrounded by the waters, before emerging saturated and maybe gasping for air.

Such a dramatic dunking was designed to signify the cleansing of the repentant person. Repentance and baptism were necessary for the ushering in of the reign of God, according to John. Jesus appears to have accepted this point of view; it is most likely that his baptism was an intense religious experience for him. He underwent a whole scale change of mind, a reorientation towards the mission that was thrust upon him.

Certainly, the way that the experience is presented by Mark (and also in the other canonical Gospels) presents Jesus as being singled out by God for a special role. There are multiple signs on the short account of this moment (Mark 1:9–11).

FIrst, Jesus sees “the heavens torn apart” (1:10). This breaking apart is mirrored in the water of the river, which parts “as he was coming up out of the water”. The breaking of the heavens perhaps echoes the cry of the prophet of old: “O that you would tear open the heavens and come down, so that the mountains would quake at your presence … to make your name known to your adversaries, so that the nations might tremble at your presence!” (Isa 64:1).

Then, he sees a vision of “the Spirit like a dove” (Mark 1:10). A dove, of course, appeared at a key moment early in the biblical narrative: as the waters of the Great Flood recede (Gen 8:6–12); but the association of the dove with the Spirit (a commonplace in our thinking today, surely) is not actually made anywhere in scripture before this moment. The dove which appears seems, to Jesus, to come from beyond rest on him, in the way that the prophet declares that “the spirit of the Lord God is upon me” (Isa 61:1). The dove brings a signal from the sky—from the Lord God, perhaps?

A third signal comes through “a voice from heaven” (Mark 1:11). This is a common note regarding the hearing of the divine voice. Moses tells the Israelites, “from heaven he made you hear his voice to discipline you” (Deut 4:36). In the wilderness, God “came down upon Mount Sinai, and spoke with them from heaven, and gave them right ordinances and true laws, good statutes and commandments” (Neh 9:13; also Exod 20:22). Ben Sirach tells the story of the judges, when “the Lord thundered from heaven, and made his voice heard with a mighty sound” (Sir 46:17). David sang that “the Lord thundered from heaven; the Most High uttered his voice” (2 Sam 22:14). So a voice speaking from heaven, in Jewish understanding, is a communication from God.

Finally, the actual words which that voice speaks are deeply significant. “You are my son” are words spoken by God to David (Ps 2:7). “With you I am well pleased” echoes what God says about “my servant, whom I uphold, my chosen, in whom my soul delights” (Isa 42:1); indeed, of the Servant, the prophet declares, God indicates that “I have put my spirit upon him; he will bring forth justice to the nations” (Isa 42:2). What is heard at the moment of the baptism of Jesus is confirmation of the place of Jesus as one beloved, chosen, and equipped by God for what lies ahead of him.

So it is that from the moment of this intense experience, Jesus was fervently committed to the renewal and restoration of Israel. His first words, as reported in this shortest and earliest account of his ministry, were clear and focussed (1:14–15). There are four key elements: fulfilment of the time, nearness of the kingdom, the need to repent, and belief in the good news. Repentance is pivotal in this succinct summary of his message. It was the heart of the message that Jesus instructed his followers to proclaim (6:12).

After this dramatic dunking by the desert dweller, Jesus left his family and began travelling around Galilee, announcing that the time was near for dramatic changes to take place. He gathered a group of men and women who accepted his teachings, journeying with him as he spread the news throughout Galilee.

The intense religious experience of his dunking meant that the fierce apocalyptic message spoken by the desert dweller was lived out in a radical way in daily life by this group of deeply committed associates of Jesus. The intense religious experience associated with his dramatic dunking by the desert dweller had a deep and abiding impact. The challenge, for those of us who follow him, is to live out this radical way of life today.